The story of Calico Jack is the tale of how two unlikely and very different wanderers met up, built their very own ‘pirate’ ship, survived a pandemic and, against the odds, now run one of the most successful liveaboards in Raja Ampat

Words and photographs Alfred Minnaar

Calico Jack is a 25-metre ‘Phinisi’ – a traditional Sulawesi schooner -with a black finish and massive red sails that truly embodies its famous pirate name. It is also the life story of two unlikely friends who, with no experience and against the odds, built a wooden boat from the ground up and kept it sailing through a pandemic that has crippled Indonesia’s tourist industry.

Calico Jack’s owners, Adam Fornasiero and Jamie Mayer, are very different characters from very disparate backgrounds. Jamie, 53, was a music producer from Camden, north London, where he worked with the likes of Robbie Williams and Tina Turner, whereas Adam, 45, originally from Albury in New South Wales, was an Australian tradesman and adventure sports enthusiast who, as a kid, was politely asked to leave school.

Not wanting to be ‘a 60-year-old wearing leather pants trying to work with 21-year-olds’ Jamie left the music industry at the age of 40, and spent two years working in Macau before he crossed paths with Adam at a party spot on Kho Phangan in Thailand. The island attracts an incredibly diverse array of people, without which Adam and Jamie would probably never have met. ‘It’s amazing how many people I’ve met that have gone through this one, dysfunctional glorious beach, said Adam. ‘Very successful people, highly intelligent people, completely useless people. It’s incredible, it’s a really funny place.’

Adam was already part of a group looking for one more investor to build a boat, but the pair did not hit it off at first. ‘My business partner introduced us, but when I spoke to Jamie, it was very awkward,’ said Adam. ‘We were already a very well-established team and he didn’t really fit because we had some very lively ‘pirate’ guys involved in this project, whereas Jamie was very interesting, very polite, you know – very English.

The second time the pair met was more productive. ‘I met Jamie in Singapore, and we all ended up going out drinking,’ Adam remembered. ‘Jamie was so drunk, he was howling at the moon in the middle of the street. Well, there we go, I thought. That’s lively, that’s interesting, that’s something we can work with. And that was how the process started.’

Through the grapevine and other ‘boaties’ Adam and Jamie were led to Bira in South Sulawesi, Indonesia, home to a unique group of people called the Bugis, known for making and sailing the wooden boats known as Phinisi. Adam and Jamie settled in a house on the beach where their boat would be built over the following two years. It would be a lesson in the Bugis culture and language which Jamie immersed himself in, becoming fluent and with a very keen knowledge of their way of life.

‘They do nothing else,’ Jamie told me. ‘They live among the wood, the chainsaws, the sawdust, the boatyards, and they’re 100 per cent a child of that process.

‘There is a deep legacy of apprenticeships, so you’ve got this overlap of probably three generations in a boatyard at one time passing on their knowledge.

‘The last of the older generation are now sadly dying out. But the guys who put our sails up used to be Bugis pirate traders in the 1960s and Seventies, running with the monsoon to do cargo, fight each other, steal off each other and raid towns for nine months out of each year.’

The arrival of engines and international visitors led to Indonesia becoming more policed, and although the piracy has declined, Bugis remain on the fringes of society, a people who care very little about what is happening in the world outside.

Walking around the beaches of Bira, the large wooden boats are an impressive sight, a scene I imagine fits better in the 1800s, before the arrival of steam engines.

In 2010, this was still the cheapest way to build boats, but 12 years later, this is no longer the case. The high price of wood means boat building is possible only for big investors, making those dreamers scraping money together to build a liveaboard, something of the past.

Adam called Bira ‘the harbour of broken dreams’. ‘The amount of people that come through with their big ideas and dreams – and then a year later it’s not going quite as planned,’ he explained. ‘I would say 50 per cent of the liveaboards are semi-successful. The others just keep changing hands.’

Calico Jack is a Phinisi adapted for diving, with five cabins. It’s evident that the boat embodies a lot of the culture as Jamie shows me blueprints for the original design of the interior carvings, which look like an old treasure map as he unfolds them. When she set sail in 2013, Adam and Jamie had no experience diving or operating a liveaboard, and admit they had no clue what they were doing. Adam describes their introduction to liveaboard diving as ‘pure luck’. No doubt luck brought on by his likeable character and ability to network in a country where who you know is sometimes more important than what you know.

Calico Jack’s first trip was as contract cover for a German liveaboard that had been impounded in Komodo but was fully booked with customers. As soon as Adam and Jamie tied up next to the vessel, engineers started transferring the dive gear and compressors, and within two days, Calico Jack was a full-blown liveaboard, operating under the banner of a company that already had ten years of experience. Over the next season, Adam and Jamie learned everything from compressor maintenance, dive routes and how to keep your beer cold at sea. They also picked up two very experienced cruise directors who remain with them to this day – something that speaks volumes in a world where staff turnover is extremely high.

Two years into a pandemic, we live in different times. Meeting Jamie in Sorong for a trip to Raja Ampat, he points out how few boats are in the harbour – and just three liveaboards. I am also based in Indonesia and have seen many tourist businesses fail. To survive, you must love the lifestyle and be extremely hands-on, something that both Adam and Jamie are, even after almost a decade in the business themselves.

We set sail for the northern reefs of Raja Ampat, heading for the beautiful Waigeo archipelago, and it is clear that this baby pirate has grown a full beard. Adam and Jamie’s immersion into the business is evident – from Jamie’s understanding of boat-building; how he and Adam know the routes and currents and at which islands to shelter from storms; and how the two are still very passionate and excited about their trips, whether that be diving, trekking into the mangroves searching for crocodiles, or exploring Raja Ampat’s uninhabited islands.

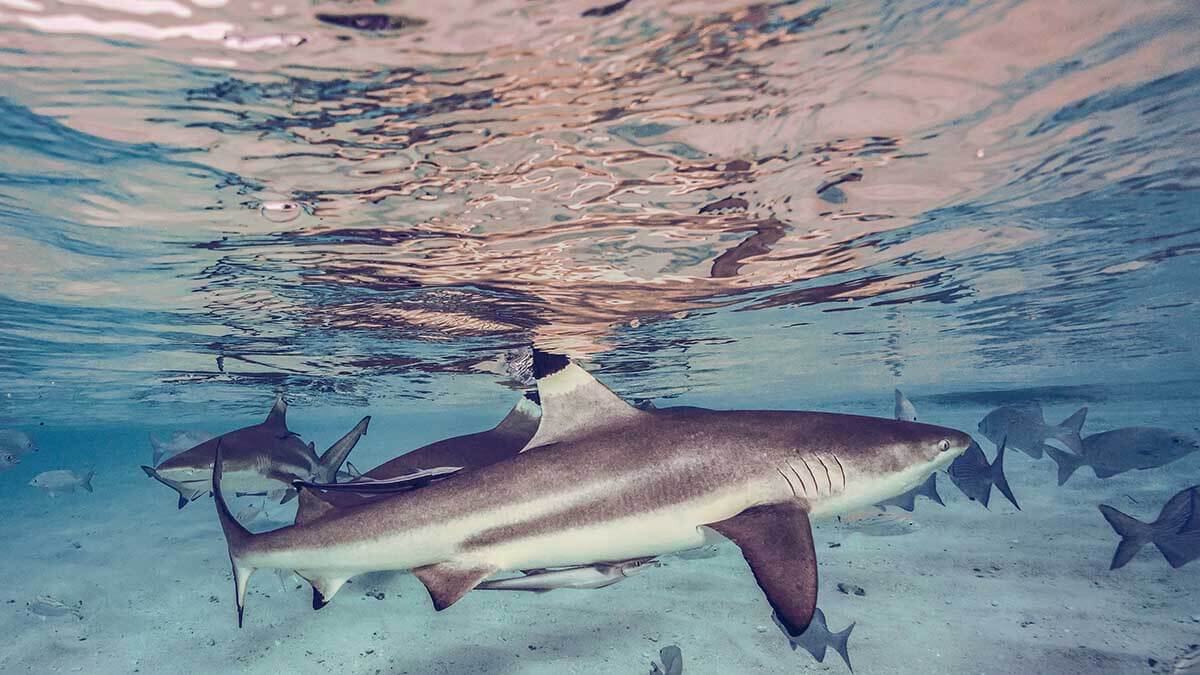

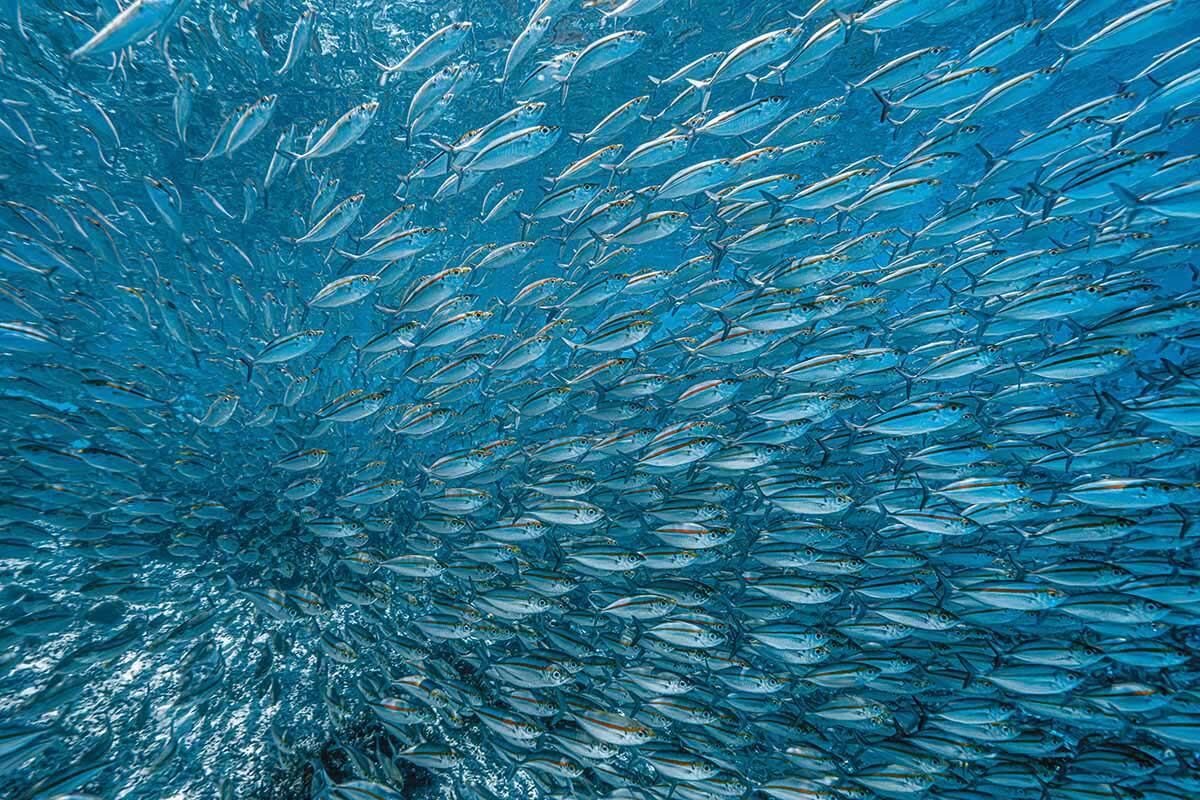

The diving never disappoints, from big schools of batfish in the shallows, to a large school of sweetlips down at 30m, all found among coral that stretches as far as the eye can see. The Indonesian government has implemented some solid conservation practices and Raja boasts a very healthy population of wobbegong, blacktip, whitetip and grey reef sharks – to the point where I found myself in the middle of a tornado of blacktips in knee-deep water in Waigeo. For those who like smaller things, the guides will happily point out pygmy seahorses among the many colourful fans.

There is an authentic family atmosphere on the boat, which is mostly crewed by Bugis. Sitting around the dinner table, Jamie and Adam tell me they are planning to add two more boats to their fleet, to be named Anne Bonny and Mary Read, contemporaries of Calico Jack and also famous pirates of their time. One of the boats is due to be launched this summer. When they talk about their boats, it’s as if the boats themselves are living entities, each one something that embodies a spirit of its own.

The pandemic has been tough for the industry, but Jamie believes those who are left standing will be stronger for it, and for Adam and Jamie it has never been about the money. ‘It was a lifestyle choice,’ said Jamie, ‘but we were canny enough to know that there was potential if we worked out the kinks. But had it failed after six or seven years, I would have still have been able to have walked away completely content with my experience.’

Few boats can claim to be built and sailed by actual pirates, and although there is slightly more sophistication behind the operation, the spirit is real. Seeing Calico Jack hoist its red sails is truly a unique sight, and an embodiment of Adam and Jamie’s love affair with the life they carved out for themselves. The only downside to owning a pirate boat in Indonesia is that the local rum is not up to standard, so if you should ever decide to sail with the Calico Jack, maybe bring a bottle with you.

www.calicojackcharters.com

More great reads from our Magazine…

- Accused: a dive instructor’s wrongful prosecution for manslaughter

- Big Shot Megafauna – THE WINNERS!

- How the Marine Megafauna Foundation makes sustainability sustainable

- Scuba diving Curaçao – a Caribbean gem

- Life Returns – coral reef restoration in Mustique

- Going Beyond: Alfred Minnaar learns to cave dive - 27 October 2022

- Ice cool scuba diving in Lake Baikal - 8 September 2022

- A pirate’s life: the story of Raja Ampat’s Calico Jack - 16 June 2022