The hot and dense jungle of the Yucatán peninsula is strangely devoid of large rivers. However, below the ground run the three longest underwater systems in the world (Dos Ojos 82km, Sac Aktum 172km and the Ox Bel Ha 270km).

The limestone slab that makes the area was once a vast underwater coral reef – today the sea has receded and over time a massive cave system has been created by slightly acidic rainwater eating away at the alkaline rock.

Ten things you need to know

1) Cave diving or cavern diving?

Well, technically they’re the same thing but different. Both involve diving in an overhead environment, but cavern diving means not straying out of the range of visible light from the surface, and not going further than 60m into the overhead environment. Cave diving is exploring beyond the range of visible light, passing into spaces that are not suitable for untrained divers.

2) Do I need a special certification?

Not necessarily. To dive the cenotes as a recreational diver, you just need an Open Water certification. To explore deeper into the underwater world, however, you need to undergo extensive cave diver training and learn how to use different types of equipment.

3) Is it dangerous?

As long as you follow some basic rules, cavern diving is no more dangerous than regular recreational diving, but the rules are different. Reputable dive centres insist on a maximum cavern penetration of 60m from the surface, maximum depth of 21m, maximum group size of four people and no passages that require the team to swim single file, and they will insist on following the rule of thirds. Cave diving, on the other hand, requires a strict adherence to much more stringent guidelines, in much the same way that deep technical diving differs from the shallow recreational world.

4) What’s the rule of thirds?

A common recreational dive plan would be to signal your team when you reach half a tank, at which time you level up, turn around if necessary and head back to the exit. Cavern diving uses the rule of thirds – that’s a third of a tank to make the dive, a third to get back to the exit, and the remaining third for unforeseen complications. It’s a standard technique for overhead environments where there’s only one way out.

5) What equipment do I need?

Normal dive gear is fine but long suits and boots are a good idea. The water temperature’s a little cooler in the cenotes than the open ocean and you may have to hike through a little bit of jungle to get to the entry point. Ditch your snorkel – apart from the overhead environment, some of the cenotes are filled with tree roots and branches, which present an entanglement hazard, and you don’t want to risk having your mask pulled off by a wayward piece of vegetation.

6) Do I need special gear?

For the basic cenote dives, you will need a torch, and preferably a backup. Although you won’t be straying too far from the visible light, that doesn’t mean it won’t get dark. Torches will help you to see more when you’re down there, and they may also be necessary for signalling to your dive group. For full cave diving then yes, you need specialist equipment.

7) I’ve read about sidemount diving?

Sidemount diving is becoming increasingly popular among the recreational dive community and is very useful for overhead environments as you wear the tank(s) slung under your arms, not mounted on your back where you are at a greater risk of bumping into things. It’s not for everybody, and you definitely need thorough preparation in using the equipment, if not a full sidemount speciality training course.

8) What about buoyancy control?

Like any overhead environment, good buoyancy control – which is important on any dive, naturally – is essential in the caverns. Bumping into things is never good, especially when there is a risk of injury or serious gear damage from sharp and pointed rocks, or entanglement hazards from vegetation. As a recreational diver, you won’t be going through any really tight squeezes, but there may be some narrow passageways you need to manoeuvre through with greater care.

9) What’s the best finning style?

Learning the ‘frog kick’ is the ideal way to dive in any overhead environment, especially those such as wrecks or caves and caverns where there may be a silted bottom. Kicking up the silt can severely impair the visibility, to the point where you might not be able to see your exit point. The standard up-and-down flutter kick will disturb the bottom even if you’re a few metres above it, especially if you’re kicking hard. The frog kick, where you bring your fins together horizontally, creates propulsion directly behind you and therefore doesn’t pick up the silt. It’s a good technique to master for all diving, but it’s the best for caverns and caves.

10) What will I see down there?

There’s not a lot of fish life in the cenotes, but that is more than made up for by the spectacular rock formations, stalactites, stalagmites and fossils, all lit by the most beautiful displays of light. You may well also encounter the spooky phenomenon of the halocline, a boundary between fresh water from the surface and heavier salt water seeping in from the ocean, which gives you the impression that you are swimming over a lake, or above the clouds.

DIVING THE CENOTES

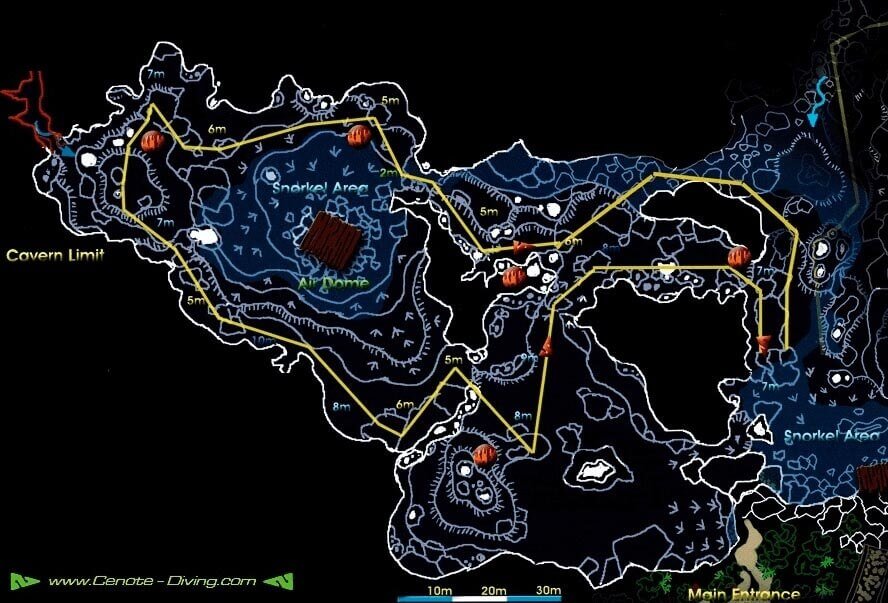

Dos Ojos & Bat Cave – Central Area

Part of one of the longest underwater cave systems in the world, it was first explored in 1987 and to date, 82km (51 miles) has been surveyed. Dos Ojos, or Two Eyes, gets its name from the shape of the two cenotes very close together. You can dive between the two and also connect to nearby Bat Cave. It is a great place to do your first cavern dive as you stay close to the surface and exit at all times.

Most guides offer two dives here – the first of the day (map above) takes you through a huge tunnel joining the two cenotes and then along the second cenote into the upstream passage of the system. At the turnaround point, you will see the famous Barbie (a toy doll tied to a rock) before returning to where you started. The second dive (map below) will lead you into Bat Cave, a huge air dome which is also accessible through a hole in the roof – where bats fly in and out.

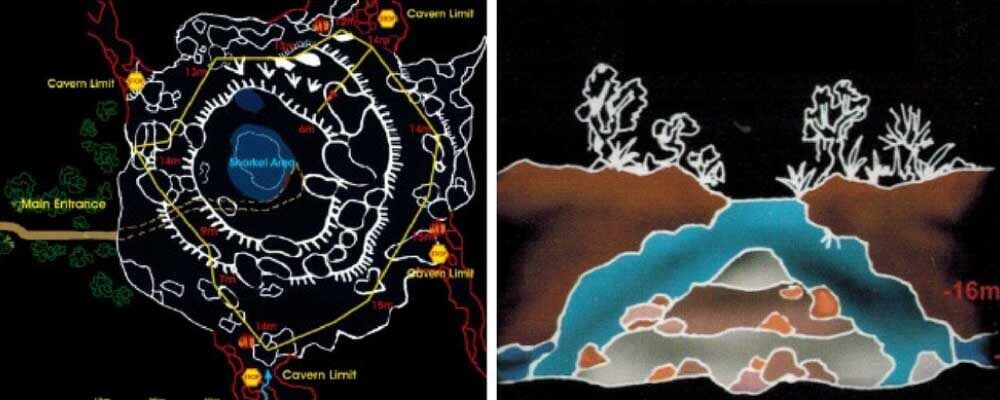

Chac Mool & Kukulcan – Northern Area

Another cenote where you can do two great dives. The first dive is normally Kukulcan (the right of the map below) – a vast open area ideal for first-time cenote divers where you can get used to diving in fresh water. In the morning there is also a stunning curtain of light which is great for photographs. There is also a strong halocline which can be disorientating for novices. The second dive takes in a fantastic dome with hundreds of stalactites. These are surreal, fantasy-world dives.

Temple of Doom – Tulum Area

Also named Calavera, which means skull, because of the three holes in the roof which give you the impression of being inside a skull. It is basically a vast hole in the ground with the water surface at a drop of about 3m. You circle a rock dome at varying depths moving in and out of haloclines which takes about 25 minutes leaving time to check out some cute stalactites in the shallower water. The limestone in the deeper sections can be bright white. The fresh water is tinged green and the salt water is crystal clear, enhancing the dramatic halocline effect. You need good buoyancy control as the sediment at the bottom is exceptionally fine.

Thanks to Cenote-Diving for the use of their maps