One of the best reasons to go scuba diving in the Egyptian Red Sea is undoubtedly the spectacular array of marine life. More than 200 different species of coral are found among its reefs, and more than 1,200 species of bony fish, at least 10 per cent of which are endemic. The Red Sea’s clear waters allow sunlight to penetrate much deeper than other tropical destinations, making the extent of coral and the vibrancy of its colour nothing short of spectacular.

SHARKS

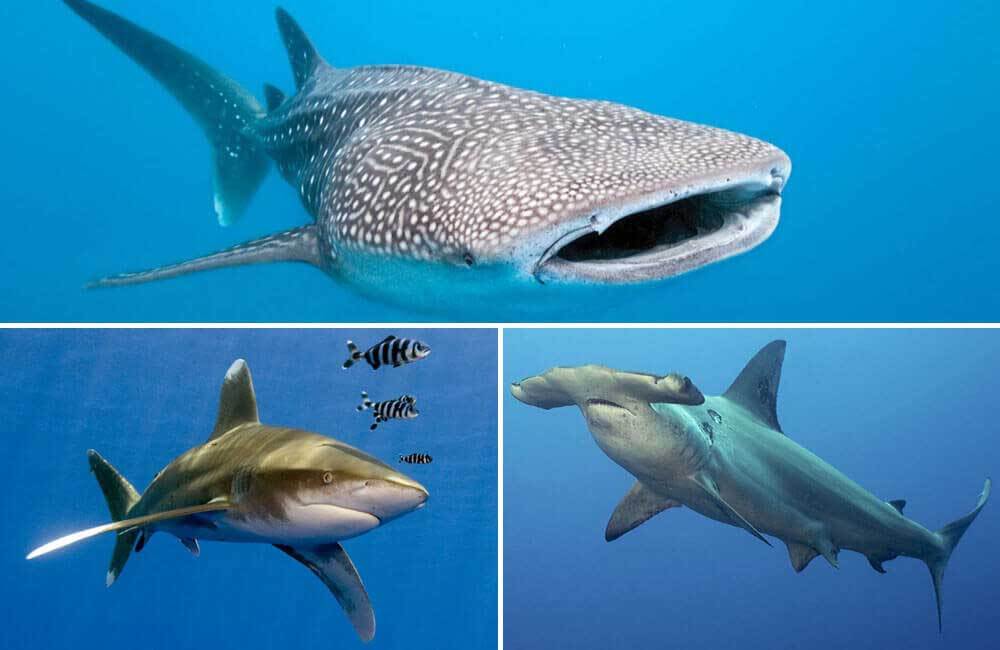

There are 44 species of shark listed as present in the Red Sea, although most of them are rarely, if ever, seen by scuba divers. Species such as the whitetip reef shark (Triaenodon obesus) and grey reef shark (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos) are two of the most commonly encountered on Egypt’s reefs, with scalloped hammerheads (Sphyrna lewini) and oceanic whitetips (Carcharinus longimanus) frequently found at offshore reefs. Whale sharks (Rhincodon typus) are infrequent visitors, but there are numerous sightings each year.

Whitetip reef sharks and grey reef sharks can be encountered at almost any dive site throughout the year. Whitetip reef sharks (not to be confused with their oceanic white-tip cousins) reach a maximum size of about 1.5m in length, with slender, flat bodies. They are easily identifiable by the white tips of their dorsal and upper caudal fins. Grey reef sharks are of the ‘classic’ shark form, with a grey dorsal fin and darker shaded pectoral and tail fin tips.

Scalloped hammerheads are mostly encountered at Elphinstone and Daedalus reefs, and further south in St John’s National Park where they can sometimes be found schooling in numbers during the summer months. They are sometimes spotted on the outside of Jackson Reef in Tiran, but surface conditions are often harsh and need to be perfectly flat to make the dive. Big-eye thresher sharks (Alopias vulpinus) are sometimes spotted in Ras Mohammed but are more often found around Daedalus and the Brothers Islands, and also St John’s between September and February

Oceanic whitetip sharks are distributed throughout the Red Sea. They are rare visitors to the reefs of Sharm El Sheikh but are spotted on an almost daily basis at the offshore Brothers Islands, often waiting underneath the liveaboards and providing close encounters with divers. They are found at other offshore reefs such as Daedalus, Rocky, Fury Shoal and Zabargad, but are most often associated with the Brothers.

Whale sharks are most likely to be encountered at the offshore reefs of St John’s in the south, and also the Brothers and Daedalus on liveaboards out of Hurghada. They can, however, turn up from time to time pretty much anywhere, including reefs much closer to shore. The best time to see them is from late spring to mid-summer, but a whale shark does what a whale shark wants. They are usually juveniles, between 3m and 7m in length, but always a thrilling encounter.

DOLPHINS

Bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) and spinner dolphins (Stenella longirostris) are regularly seen frolicking at the surface during boat rides between dive sites throughout the Red Sea, but – with a few exceptions – are less regularly encountered on the reefs while diving. One of the best places to see bottlenose dolphins underwater is at Sha’ab El Erg (sometimes called Dolphin House), which is a popular dive site on day trips from Hurghada and El Gouna and the surrounding area. Spinner dolphins create a spectacularly acrobatic show as they follow the dive boats, but can be regularly found chilling at the reefs of Dolphin House in Marsa Alam.

Risso’s dolphins (Grampus griseus) are identifiable by their rounded heads and much shorter beaks than other species of dolphin. They are often called ‘beluga’ by local boat crews, a nickname inherited from a case of mistaken identity due to the dolphin’s similarity to beluga whales. Risso’s dolphins prefer to spend their time in deeper waters and are rarely seen when diving on the reefs. One of the best places to spot them is the deep water saddle between Jackson and Laguna reefs near the island of Tiran in Sharm. They can often be seen displaying in groups, with their tail flukes held vertically out of the surface of the water.

RAYS

Both the reef manta (Mobula alfredi) and giant/oceanic manta (Mobula birostris) can be found in the Egyptian Red Sea, although little is known about their distribution. It is thought that the smaller reef manta is more likely to be seen along the shallower reefs of the mainland coast from Hurghada to Marsa Alam, and the oceanic manta more likely to be encountered at deeper reefs such as Shark and Yolanda in Sharm, the Brothers Islands, and more frequently at St John’s, Zabargad and Rocky Islands. Spotted eagle rays (Aetobatus narinari) can be found throughout the Red Sea, often cruising along the drop-offs as the reef plummets into the depths. Keep an eye out for feathertail rays (Pastinachus sephen, also called cowtail and fantail rays) digging around in shallow sandy patches on the lookout for shellfish – at well over 2m long fully grown, they’re difficult to miss!

BLUE SPOTTED RAYS

One of the most iconic species of the Red Sea and deserving of an entry of its own, the blue spotted ribbontail ray (Taeniura lymma) – is a common species of stingray almost guaranteed to be sighted on any dive at an Egyptian reef. Although it is part of the family of stingrays, it is often mistakenly labelled as the ‘blue spotted stingray,’ which is a different species and not present in the Red Sea. The striking blue-and-gold colouration makes them easy to spot amongst the coral, and although the sting is extremely painful, blue spotted rays are generally placid and will allow divers to make close approaches, making them perfect subjects for photographers.

NAPOLEON WRASSE

Regularly encountered throughout the Red Sea, the Napoleon wrasse (Cheilinus undulatus), sometimes called the humphead wrasse, is another Red Sea favourite. Adults can grow to over 1.5m in length, and often make their home at a single reef, where they can be spotted on a regular basis. Although they are mostly solitary, they are sometimes seen in small groups, usually with one larger fish accompanied by smaller companions. Napoleon wrasse are highly inquisitive and will often make close approaches to divers, even following along as a big green buddy for several minutes at a time.

GIANT MORAY

Instantly recognisable by its large head poking out of a crevice in the coral, the giant moray (Gymnothorax javanicus), at up to three metres in length, can look particularly frightening as it bares its sharp and pointed teeth while opening and closing its mouth to pump water across its gills. They are not aggressive animals and are more likely to turn and flee if a diver gets too close, but unwary poking around in dark holes can result in a nasty bite. They hunt at night, making for wonderful night-diving encounters, and are sometimes spotted free-swimming during the day, always a mesmerising sight. The much smaller geometric moray (Gymnothorax griseus) – sometimes called the grey or peppered moray – is more common, but less easy to spot due to its size. Also keep a look-out for the yellow-edged moray (Gymnothorax flavimarginatus), about half the size of a giant moray and double the size of the geometric, but also regularly spotted among the Red Sea’s reefs.

LIONFISH

Another iconic Red Sea species, there are several species of lionfish found in the Red Sea, but by far the most frequently spotted is the common lionfish (Pterois miles), sometimes called the turkeyfish. Possibly the most beautiful ugly fish found on Egyptian reefs, their dorsal spines are highly venomous and extremely painful and have – on very rare occasions – proven fatal to unwary humans. By day they are languid swimmers, often found sitting near motionless on blocks of coral, but will dip their heads and display their spines towards divers that approach too closely. By night, they are a different animal; voracious hunters flitting around the reef at lightning speed. Night divers will often find lionfish following the beam of their torches, and any unwary small fish caught in the light will be devoured in an instant.

STONEFISH

Distantly related to lionfish and also scorpionfish, the reef stonefish (Synanceia verrucosa) is the most venomous bony fish found throughout the world’s oceans. Toxicity of the venom varies between regions but a sting from the dorsal spines is agonisingly painful and occasionally lethal. As the name suggests, stonefish have evolved to look like lumps of rock, usually with a dark skin tone interspersed with patches of colour to resemble coral, sometimes with dark green appendages giving the appearance of a rock coated in algae. They are poor swimmers and rather comically bounce along the bottom when they do move, but are capable of short bursts of speed. Stonefish camouflage makes them difficult to spot, one of many reasons that divers should never touch any part of a coral reef, and they sometimes bury themselves in the sand, meaning extreme caution should be taken when kneeling in the sand to take photographs.

LONG-NOSED HAWKFISH

A photographer’s favourite, the delightful long-nosed hawkfish (Oxycirrhites typus) is found hanging around near gorgonian fans and black coral bushes throughout the Red Sea. Growing to a maximum length of around 10cm – and usually smaller – its red and white chequered stripes make the fish difficult to spot, but once it’s been observed it will often sit still, relying on its camouflage to remain hidden, although, to human eyes, it isn’t. The long-nosed hawkfish is also every English-speaking dive professional’s favourite fish to pronounce in German – the langnasenbüschelbarsch has a ring to it that the English version doesn’t.

TURTLES

Green turtles and hawksbill turtles are common to all regions of the Red Sea. The big green turtles (Chelonia mydas) can grow up to nearly 2m in length, and are often found munching on seagrass beds with large remoras clamped to their carapaces. They are incredibly tolerant of divers, to the point that they will ignore a camera lens even when taking close-up shots. Hawksbill turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata) are mostly to be found in rich coral gardens, and although they are more wary of divers, it’s unusual to get through a diving day without seeing at least one somewhere.

TITAN TRIGGERFISH

Another famous face that only a mother could love, the titan triggerfish (Balistoides viridescens) has a reputation for menacing divers that is unmatched by almost any other sea creature. For most of the year they remain placid, often seen blowing up clouds of sand as they dig for shellfish, and remain unperturbed by divers. The spiny-shaped dorsal fin is raised as a warning to divers that get too close, but by and large, they swim away and dig around elsewhere. During mating season, however, the titan will defend its nest against anything and everything that strays too close. They will attack on sight and they will not stop until the diver has left the area. The best advice is to swim away and – if possible – down the reef, but keep your eyes on the fish – the titan’s teeth evolved to crush coral, and a bite can cause serious injury.

DUGONG

The dugong (Dugong dugon) – also known as the ‘sea cow’ – was once thought to have a population numbering in the thousands in the Red Sea, but hunting and the depletion of seagrass fields over the years have rendered them vulnerable to extinction. Dugongs are relatives of manatees, and together they are the world’s only known herbivorous aquatic mammal. Like their land-based cousins, sea cows graze perpetually on seagrass fields, eating up to 40kg and more per day. There is thought to be a population on the far side of Tiran island which is strictly off-limits to dive boats, and the only place they are regularly spotted by divers is in the Abu Dabbab region of Marsa Alam. There may be only a handful of individual animals along much of the Egyptian Red Sea’s coast so care must be taken not to disturb the animals.

CLOWNFISH

There is a variety of anemonefish in the Red Sea, but it is the Red Sea clownfish (Amphiprion bicinctus) with which everyone will be most familiar. Since the launch of the cartoon movie ‘Finding Nemo’, it has become almost mandatory for divers to photograph a ‘nemofish’ and caption it on Facebook with the words ‘I found Nemo!’ even though Nemo himself was based around a different species, the ocellaris clownfish (Amphiprion ocellaris), which doesn’t live in the Red Sea. The Red Sea clownfish spends its entire life living among the stinging tentacles of a variety of anemones, with each species providing protection to the other. Clownfish are among the most sought-after subjects of photographers and look out especially for those that live among the rare red anemones. Rather like the titan triggerfish, clownfish can be very aggressive when defending their young, and although their jaws are too small to cause serious injury, it’s not unheard of for divers to receive small bites if they get too close to ‘Nemo’.