Mark ‘Crowley’ Russell talks to Dr Andrea Marshall and Dr Simon Pierce, co-founders of the Marine Megafauna Foundation, about the decades of hard work that sustainable conservation requires

Sustainability is an environmental buzzword sometimes bandied about as if it can be switched on at a moment’s notice. But sustainability only works if something sustainable is created to sustain it, and that means digging in for the long haul – being prepared to face years, decades even, of adversity to achieve your goals.

‘I just don’t think people have any idea of what that word means,’ says Dr Andrea Marshall, rather bluntly, ‘because they use it so casually. Like “capacity building”, another term I hate, because building capacity is not something that is done in a week, or a month or a year – that is a very long build.’

Marshall fully understands what sustainability involves, having devoted two decades of her life to studying manta rays and other megafauna in Mozambique. She was the first person to do a PhD on mantas; formally described a second species in 2009; and co-founded the Marine Megafauna Foundation (MMF) with friend and colleague Dr Simon Pierce. It is evident when she speaks that Marshall remains fiercely passionate about the work she began 20 years ago.

Through the Instagram-filtered lens of the modern world, marine science and conservation often appear at the surface to be a life spent patrolling the sun-drenched, deep-blue ocean looking for whales to save and sharks to commune with, but the reality is decidedly different. Behind the glossy pictures are challenges that are largely unimaginable to viewers from the comfort of their smartphone screen but which scientists and conservationists in the field face daily.

‘When people hear you’re a marine biologist – especially as a female, of course – everyone imagines you fluttering around in a bikini all day, hand-feeding dolphins,’ says Marshall. ‘People often talk about the successes, you know, or winning an award or something like that, but these little moments are hard-won, and they are interspersed with really gruelling, very difficult, challenging moments in between and people rarely talk about that.’

Marshall first visited Mozambique in 2002, a nation then recovering from a brutal civil war between 1976 and 1992, and a prior decade-long war of independence from Portugal. Parts of the country were still land-mined; the single arterial road was filled with potholes ‘the size of refrigerators’, making it a dangerous and difficult place to get around in and work.

Her trip passed through the province of Inhambane – now designated a ‘Hope Spot’ by Sylvia Earle’s Mission Blue Foundation, thanks in part to MMF’s efforts – where large marine animals were present in numbers that Marshall, who was working for the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) at the time, had not encountered before.

‘I had never seen [Inhambane’s] equal in terms of marine megafauna,’ she says. ‘You could almost walk on the backs of whale sharks; they looked like leaves scattered at the surface. We’d go on a dive, and there would be 30 mantas and a bunch of other rays and sharks, and whales breaching everywhere. And I thought: “What the hell is this place?” So, as bad as it was on land, I just was like, I’ve got to stick my flag in this.’

Marshall had written the first assessment of manta ray populations during her time with the IUCN, and, disappointed with its ‘data deficient’ result, returned to Mozambique in 2003 intent on addressing the shortfall of research.

Starting up in the war-torn, desperately poor country, however, was not easy. ‘It was hard going, those first few years,’ she says. ‘I built a little leaf hut. I mean, it was genuinely woven out of coconut leaves. We had no electricity, we had no running water – we had to pump all our water and then heat it by burning coconut husks just to get a little hot water.

‘It was impossible to communicate with anyone,’ she adds. ‘We still had dial-up internet, so I had to drive an hour and a half to determine even if it worked, and then drive all the way back, just to send an email. I’d have to walk up a dune for a kilometre just to get a [phone] signal.’

Self-funded and working by herself, she bought a small boat and trained a local man to act as surface support for the hundreds of solo dives she undertook, instructing her new deckhand to watch out for her in the water, but never switch the boat’s engines off for fear he would not be able to restart them to collect her at the end of a dive – a dangerous undertaking with no nearby emergency support.

‘But – the diving was so amazing!’ she says. ‘And the potential for research and conservation was so amazing that my 20-year-old self just told myself, “You can do this”.

‘But it got hard. I almost got scurvy; there were no fresh fruits or vegetables, and I started to get sick because I was eating beans out of a can and two-minute noodles, and you can’t really live on that in those conditions very well.

‘I got every illness you can imagine, we lived through a giant category-five cyclone, and we had several major fires, one of them that burned my research centre down around about a month after it was completed.

‘I look back and I think “What on earth was I thinking!” But I was very determined, because when I first moved out there, everyone told me I wasn’t going to make it, so I just couldn’t quit because I just couldn’t let them be right. But yeah, it was real hard. And I remember asking Simon to come out and being, like, I could use a little help out here….’

Marshall and Pierce had met through the University of Queensland in Brisbane, Australia, where they were both doing their PhDs, although Pierce was mostly focused on Australia’s coastal shark species at the time. He put his PhD on hold to move to Mozambique and spend some time ‘hanging in the field’ to help his colleague.

‘It was a huge culture shock,’ says the characteristically – possibly pathologically – humorous Pierce, of the moment he first arrived in Mozambique. ‘It was my first time in Africa, so I kind of thought lions were going to jump me as I got off the plane. It was definitely a big learning curve coming from a pretty sheltered life in New Zealand, where everything is like rainbows and unicorns.’

‘There were some pretty crazy bugs, then you’d hear this weird noise and then be like “Oh my god there’s bats in the roof!” And then you’d hear another weird noise and see a snake crawling through the roof slats to go and get them – I called it the “ecosystem approach to house maintenance”!’

‘I don’t think I left for about three months, and then went down to South Africa and walked into the first supermarket I could find, and it was just like the Promised Land, with choirs of angels singing. I wanted to lie on all the cheese, because there was just so much we couldn’t get in Mozambique.’

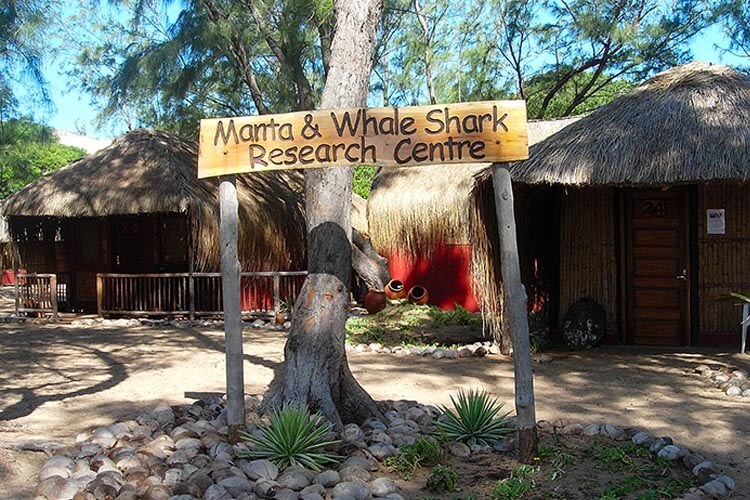

Today, MMF is at the forefront of sustainable marine science and conservation, with nearly 140 papers published by affiliated researchers since its inception. What was once a beachfront hut with a wooden signpost naming it the Manta & Whale Shark Research Station has become a globally recognised organisation which, although still relatively small, has operations spanning the Americas, Western Indian Ocean and South East Asia.

MMFs success has been hard-earned, however, and the story of its founders brings to the fore the reality of a life in science and conservation, particularly in still-developing nations where the culture, politics and economic status of the local population can be drastically different from what others might consider to be a more progressive, ‘developed’ world.

Many people will recognise that there is a vast difference between passing through a country on vacation and living and working within the different culture of a foreign land, especially one that, in the case of Mozambique, had essentially been shut off to the ‘developed’ world for the latter half of the 20th century.

There is also a substantial disconnect between the way people who pass through on a short-term basis perceive the activities of fishers who are taking from the ocean what are otherwise considered to be endangered species. Blame is often laid at the door of the people who commit the deed, rather than the reasons for which they take such actions.

To a poverty-stricken population, the future of a threatened animal species is of little importance when your children are in danger of having no future at all. Whale sharks and manta rays are simply resources for use in the same way that other cultures rely on industrially-farmed cattle and sheep; easily accessible sources of protein and, latterly, extra income from the sale of fins and gill rakers to the international gangs who bear sole responsibility for their illegal trade.

The lengths to which such people will go to protect their livelihoods was grimly illustrated when, following an emotional confrontation during which Marshall tried to persuade a group of fishermen who had caught four mantas – still alive in their nets – to let their catch go free, the research station’s pet dog was killed and mutilated and left on the research station’s doorstep as a warning to stay out of their business.

The experience was a sobering one: several hundred conservationists around the world are killed each year by people who object to their activities.

‘I realised I needed an about-face in terms of my approach,’ says Marshall, ‘and that’s when we started to heavily invest in education. This wasn’t just me yelling at them on the beach, telling them what they’re doing is wrong; this was about sustained education. Not stopping them from doing anything, just let’s have conversations under the trees; let’s start getting your kids into marine courses. I don’t care if this is going to take 20 or 30 years; this other approach isn’t going to work.

‘Things got infinitely better when we did that, but it took a moment like that for me to realise that I can’t just stop people from doing something, I have to teach them why we can’t do these things.’

Therein lies the lesson of successful sustainability. MMF’s long-term investment in education has reached a level where, two decades after those first confrontations, native Mozambicans – and other nationalities from across MMFs areas of operation – are now heading to university to become marine biologists, with a new generation of Mozambican children being taught about the environment by a previous generation set on a path laid out by the MMF co-founders’ vision.

‘I think conservation organisations are on a kind of a continuum,’ says Pierce. ‘Sometimes the people that make a lot of noise are very good at drawing public attention to something and getting media interest, because media loves conflict. Whereas with our science training, we are more of an intermediary.

‘Activist groups can be really good at pointing out a problem, but community members often don’t want to work with them, because they don’t like being painted as the bad guys, though they will often work with us, but in a less confrontational manner.

‘Most of our work has been in some of the poorest countries in the world, and we’re dealing with people whose unsustainable activities are coming from a place of poverty,’ adds Pierce, ‘so we’re trying to work with them to solve the problem. Rather than take away their livelihood, you’ve got to come up with an alternative. It might not be as lucrative. But it might well be better.

‘When you talk to the shark fishers in Mozambique, they don’t like their job. It’s super-hard; it’s dangerous, they’re at sea in all conditions, and most of them can’t swim. And so if you can hook them up with a job like being a deckhand at a dive centre or something, well, they’ve got a much better job. They love it. So if we can find those opportunities, then that’s kind of the win for us.

‘I learned quite early that, as a biologist, I was thinking about conservation as a biological concept – about the animals. But you realise quite quickly that conservation is actually all about the people. These people have significant problems that they are trying to solve through sometimes unsustainable fisheries and things like that.

‘Conservation is basically helping them solve their problem so they can do something that is better for the animals.’

Ultimately, most of the problems conservationists face boil down to cold, hard currency, but paying people off by throwing money at them is not a sustainable solution for the long-term survival of the ecosystem.

Funding is scarce; support is not guaranteed; campaigns rise and fall on the whim of a fickle media. The only sustainable solution to conservation is to get people to understand the need to invest in their own futures, by providing them with alternative resources so they are no longer dependent on placing their own survival over that of a species under threat of extinction.

Over the years, scuba diving has become a part of that education. In the Mozambican megafauna hotspots of Tofo, Inhambane, and Bazaruto, diving is now a well-established business, gainfully employing locals who now have a vested interest in the survival of ecosystems which, as a result, are being turned into marine protected areas.

‘Older fishers could see that the fishing wasn’t nearly as good as it used to be, and a lot of them blamed diving,’ says Pierce. ‘They thought that the divers scared away the fish, [but] as they learned to dive, they could see that wasn’t true.’

It is more than two decades since Andrea Marshall planted her flag in Mozambique, and 14 years since she and Pierce officially launched the Marine Megafauna Foundation. They are rightfully – if modestly – proud of their achievements in both science and conservation, but neither is satisfied that their work is complete. If anything, Marshall suggests that, even after 20 years, it has only just begun.

‘This whole ‘parachute’ science, or conservation, where people flitter in for two weeks, or a year, and then leave, passing all kinds of judgement and making all kinds of comments, that’s just not very helpful,’ says Marshall. ‘You have to do the hard work; you have to put the time in.

‘In Mozambique, I feel like we’re just gaining momentum now, after 20 years on the ground, of really hard work – 365 days a year, full-time for 20 years – that’s the kind of effort that it takes to even break ground and make a little impact.

‘You cannot just go in and tell someone they can’t use their resource unless you offset that with something else. But you also have to educate them so that over time they realise that they’re doing the right thing, because that’s ultimately what it takes to have sustainable conservation.’

More great stories from Marine Megafauna Foundation

- Whale shark reproductive ultrasound study published

- World’s largest oceanic manta ray population in Ecuador, says MMF study

- Inhambane Seascape named Mission Blue Hope Spot

- The big questions remaining about whale sharks

- Prince Harry visits MMF project in Bazaruto, Mozambique

- Full Circle – a return journey through 25 years of Sharm El Sheikh - 25 February 2026

- Hollis 200LX second stage regulator recall notice - 25 February 2026

- Student diver dies during training dive in Golfo Nuevo, Argentina - 20 February 2026