A coral restoration programme and an environmental clean-up around the island of Mustique have brought a remarkable amount of marine life back to a once-bleak Caribbean reef

Words and photographs by Douglas David Seifert

As with much of the Caribbean, the reefs around the tiny island of Mustique have suffered over the past 50 years – hurricanes, devastating marine pathogens, overfishing, polluting runoff from tourist development, and other calamities had left them in a sorry state.

When Colin Tennant, Lord Glenconner, bought the island nearly 60 years ago and turned it into a private haven with a few homes, the rich and sometimes the famous (Princess Margaret was a regular guest) could snorkel some of the best coral reefs in the region. However, as the island developed, wastewater, fertiliser, and chemicals found their way into the sea, which lessened the corals’ resistance to disease.

In 1986, Tropical Storm Danielle exacerbated this pollution, which caused wholesale devastation of the reefs in Plantation Bay off the island’s southwestern shore. In 1983 and 1984, a mysterious disease wiped out populations of long-spined sea urchins (Diadema antillarum) throughout the Caribbean.

Sea urchins are keystone species, essential to keep the algal growth in check on healthy reefs. Coral polyps could not recolonise the damaged reefs without the sea urchins grazing on the quick-growing algae. The beautiful reefs of Mustique became but a fond memory.

In the years that followed, Mustique’s 100 or so homeowners created an environmental committee. Freshwater and greywater runoff into the ocean was stopped by constructing retaining walls and capturing effluent in soakaways. Raw sewage was treated, and toxic chemicals and fertilisers were phased out. The lagoon on the island’s south side was restored, and mangrove areas were replenished.

In a short period of time, the water quality in Mustique’s nearshore waters began to improve. Chairman of The Mustique Company’s environmental committee, musician Bryan Adams, invited coral restoration expert Ken Nedimyer to assess Mustique’s coral reefs. Nedimyer and his team found that although the reefs were degraded and struggling, the situation was not altogether hopeless. He proposed to rewild the reefs through coral plantings.

In 2015, Nedimyer set up a coral nursery, seeded with fragments of locally harvested elkhorn coral (Acropora palmata), staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis), and blade fire coral (Millepora complanata). They suspended these fragments in the water column of L’ Ansecoy Bay, hanging them from fiberglass ‘trees’, buoyed by flotation and anchored to the bottom in eight metres of water.

The fragments thrived and were soon harvested and broken down into 2.5cm by 2.5cm ‘frags’ and attached to bare rock with marine epoxy. The coral began to grow and establish limestone skeletons, creating their own stable anchors to the rock substrate. The tiny fragments of elkhorn and blade fire corals thrived in the shallow water.

Elkhorn coral can grow 5cm to 25cm in a year, and their colonies can live for decades, ultimately reaching 1.8m high and 4m wide under ideal conditions. Tidal surge and wave action continually massage the island, providing oxygenation and a steady supply of food — a mix that enables the elkhorn corals to thrive.

During the pandemic, Douglas spent 300 hours underwater documenting the coral reef restoration programme. He would like to thank Raymond ‘Rock’ Dewer, Keon Murray and Gilan Comas for providing the endless air cylinders. His images are showcased in a book with topside photographer Lawrence Worcester – Wild Mustique, out in March 2023.

Email marketing@mustique.vc for further details.

However, the staghorn corals have not fared as well, growing for a time but then getting smothered in mats of macroalgae that also thrive in the shallow, sunlit waters. It has been seven years since the initial coral plantings, and the elkhorn corals have grown and expanded into impressive thickets.

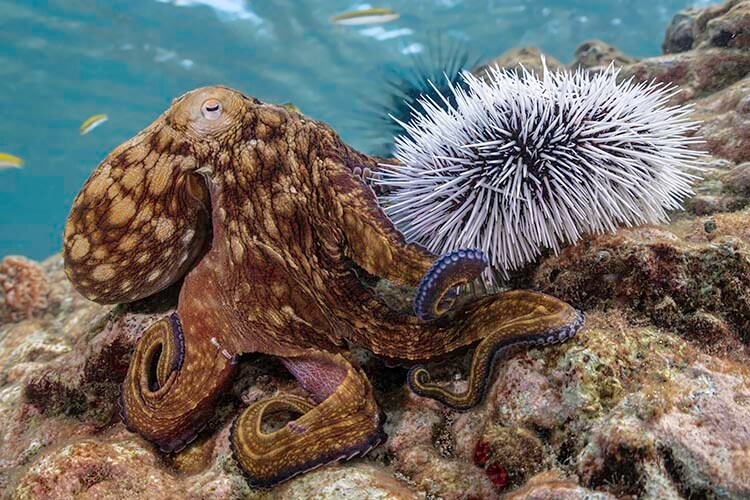

The coral branches shelter a variety of fish species, including squirrelfish, grunts, porcupinefish, trumpetfish, damselfish, angelfish, butterflyfish and eels, as well as invertebrate dwellers such as sea urchins, lobsters, and octopuses. Cleaning stations abound where juvenile Spanish hogfish and various species of cleaner gobies provide an all-day parasite removal service for a variety of larger reef fish visting the site.

Common octopus (Octopus vulgaris) are frequently seen, going about their shape-shifting business of hunting, mating and generally delighting snorkellers and swimmers with their goings-on. Reef squid are commonly seen near buoys marking the roped demarcation of the boat exclusionary zone.

Green sea turtles also feed on the seagrass beds of Endeavour Bay, and eagle rays make frequent flybys as they root around in the sand for food. Stingrays make occasional visits, as do hawksbill sea turtles.

The coral nursery has been moved to the more sheltered Endeavour Bay, where it can be viewed by snorkellers making a short swim from the wooden jetty of the Cotton House Hotel. The nursery was not moved for public relations purposes, it just so happened that the new location was more protected and easier to maintain for the coral ‘gardeners’ whose duties involve regular scrubbing of the fragments to remove encrusting algae and marine worms.

The reef has become busy, populated, and vibrant. Since 2015 more than 12,000 coral fragments have been planted along Mustique’s coast. The goal is 100,000 plantings by 2030. The biomass of fish is increasing, and the quality of sea life encounters is improving.

But reef rewilding (restoration) does not equate to a return to nature in its original state. It involves making smart decisions, prioritising the greater good, and achieving what is possible. Planting two or three types of coral in a locale that was once home to dozens of species may seem meagre, but it is a start. Recreating nature, or attempting to, is not without physical and financial costs, which the volunteers and community members bear.

While it’s still a work in progress, the restoration and rehabilitation of this formerly austere rock reef into a coral garden brings a great sense of achievement to the island community and its visitors, and provides an example of a positive way forward for reef stewardship.

More great reads and stunning images from Doug Seifert