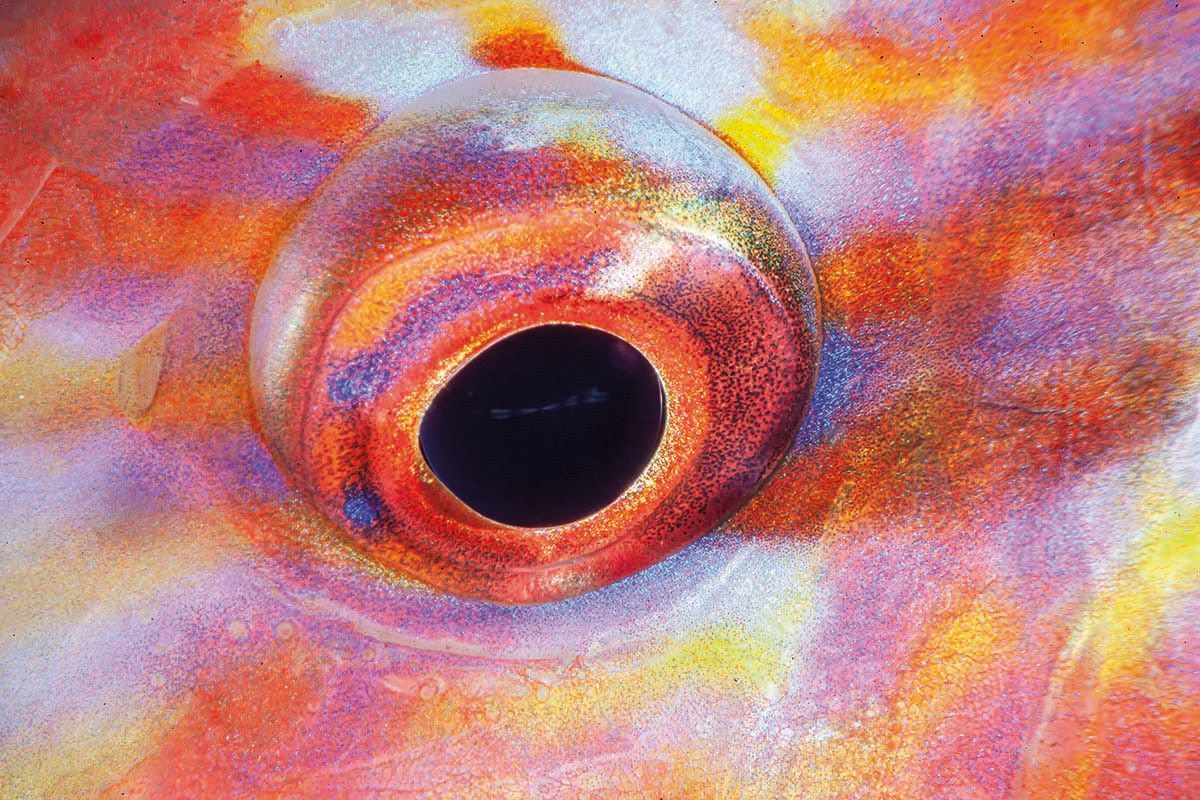

For fish, and humans, vision is the most important sense in understanding the outside world. Douglas David Seifert takes a close look at how fish and other marine creatures see underwater

Vision is by far the dominant sense shaping human perception of the world, so it is not surprising that a fascination with the eyes and visual systems of other species has an irresistible appeal. This is a universal instinct among vertebrates across all species, to identify the eyes and thus to instantly determine the gaze, establishing the attention or unwariness of any animal encountered, whether it be a kindred species or something completely alien.

The first tendency upon encountering another animal of any kind is to rapidly determine where the animal’s eyes are located. This gives the essential information of where the head, brain and mouth are situated and in what direction the animal is oriented.

Appraising the gaze – which we call eye contact – is crucial for determining whether the encounter is with a predator or with potential prey; or if the subject is a territorial or reproductive rival. It is the essence of the phrase ‘life or death’. It distinguishes whether the subject can be disregarded as non-threatening or neutral and therefore relegated to the background.

Vision, simply described, is the result of detecting and processing visible light (electromagnetic radiation) on a light-sensitive receptor which transmits a signal to be interpreted by the brain.

No one knows for certain when the first organisms originated photoreceptive organs, but current scientific thought suggests that one billion years ago, elementary multicellular animals divided into two physical frameworks: those which were radially symmetrical, and those which were bilaterally symmetrical (with right and left flanks mirroring each other, and a defined posterior and anterior). These bilateral animals diverged some 600 million years ago to create the invertebrate and vertebrate lineages that exist today. Primitive vision was probably a simple light-sensitive photoreceptor cell and pigment cell combo called an eye patch, as is found in today’s marine flatworms. The eye patch functions to regulate circadian rhythms – alerting the animal to when it is daylight or darkness – rather than providing much information about its surroundings. Further refinements in design brought forward the pigment cup eye, in which the retina is cupped, and thus light can only enter from one direction, giving an indication specifically from where the light originates, as is found in the gastropod mollusc limpets and in bristleworms.

During the Cambrian Explosion, 541 million years ago, a mass divergence and diversification of animals occurred over a 25 million-year period and set the stage for the majority of animal species living today.

During this time of evolutionary experimentations, ancestors of today’s cephalopods proliferated throughout the seas, from which the first nautiloids evolved and continue to this day in six species of nautilus. The nautilus evolved a pinhole eye, open to the environment, also known as a camera obscura, wherein a tiny opening in the eye serves as an aperture and permits light to enter and form a dim, inverted, and somewhat blurry image on the retina, giving the most rudimentary vision.

During these evolutionary visual experiments, several successful visual systems developed along two very different trajectories that carry forward to this day:

the compound eye and the camera-type eye.

The compound eye is a honeycombed, spherical array of multitudinous, hexagonal, identical imaging modules, called ommatidia, oriented to point in slightly different directions. Each acts as a lens or reflector, to transmit light to light-sensitive photoreceptors, that give the animal enough information to perceive its environment. Compound eyes are widespread throughout insects, crustaceans and stomatopods (mantis shrimp).

The advantage of compound eyes is a very wide field of view and the facility to detect rapid movement – as much as twelve times faster than typical vertebrate lens-type eyes, although at the expense of image resolution (clarity). Mantis shrimp eyes move independently, and constantly scan the environment. They have twelve different receptor types in their ommatidium arrays, compared to the three types found in humans, and four kinds found in fish, giving them an ability to see in the ultraviolet spectrum and in polarised light, though they don’t see colours particularly well. They are perfectly able to perceive the world in three dimensions and are accurate in distance estimation.

The camera-lens-type eye is found in all vertebrates, terrestrial and aquatic, as well as non-nautiloid cephalopods. It is not surprising that humans and fish should share a similar eye design, as all descend from the same distant ancestor, but it is curious that octopus and squid, which share no common ancestor with humans or other vertebrates, would develop a similar but slightly different camera-lens-type eye as an example of parallel evolution.

The camera-lens-type eye has a single lens, which creates the sharpest image resolution and light sensitivity. In terrestrial vertebrates, light enters through the cornea, where the light rays bend on the curved surface of the eye, and passes through the central pupil and surrounding iris and onto the clear lens. Here the light is further focused to fall upon the retina, which lines the rearward curved wall of the eye.

The retina is the site of light-sensitive cells called rods and cones, which collect information and transmit it via the optic nerve to the brain. Rods are sensitive to low light and do not detect colour but allow greater vision in dim illumination. Cones have the greatest resolution and excel at detecting motion. In many species, they also provide for colour vision.

In fish, because the surrounding water is equivalent to the aqueous humour (liquid) within the eye, and thus the light rays do not bend at an interface between air and lens, only the lens is of importance. Unlike terrestrial vertebrates, fish eyes do not possess a mobile pupil and the cornea is inefficient, so the lens does most of the work to achieve vision in the near, intermediate and distant ranges.

This is achieved by changing the lens position in relationship to the retina. If the lens is drawn close to the retina, distant vision is achieved; if the lens is deployed outward, near-vision is dominant. With many demersal and reef fish, the default setting for vision is this near-vision, which allows the ability to see close to the fish as well as having a wider angle of view than when the lens is pulled back for distance sight. Predatory fish, particularly sharks, billfish, tuna and jacks, default to their distance vision for greater facility at detecting prey at distance while hunting.

Most reef fish see in colour quite well. They see what humans see, even if they may process that information differently, in terms of brightness and reflectivity. Humans are trichromats – having three cone receptors, blue, green and red – while most fish are tetrachromats, having an additional cone attuned to the ultraviolet spectrum. This allows fish to see signals and patterns invisible to humans on the bodies of their conspecifics, their mates, their neighbours.

Octopus vision differs slightly in that the cornea sits atop the eye, and thus light is transmitted directly from the lens to the retina without having to pass through tissues, providing the octopus with more contrast and less interference in processing visual information. The octopus eye focuses by movement, often independent, and muscular expansion, contraction and manipulation. They can see polarised light, which may contribute to their prowess in communicating with each other, hunting and navigation.

There is considerable debate as to whether octopus and other cephalopods can see colour. They possess only one type of light receptor, which should mean they can only see in black and white and shades of grey, yet the ability to manipulate their U-shaped or W-shaped pupil may allow light to enter the lens from many directions. This creates an accentuated chromatic aberration which is exemplified by an image framed with colourful fringes that give the cephalopod enough colour information to perceive its world.

It has been said that ‘eyes are the window to the soul’. They are the shared sensory organ we find fascinating in all creatures great and small, on land and under the sea, and which bind all species together, giving each animal the mechanism to better see you with.