Temperate reefs can be as rich and vibrant with life as their tropical counterparts as Douglas David Seifert discovers exploring the best dive sites of Vancouver Island, Canada

The western shore of Canada is a rugged, rocky, 27,000km coastline of temperate coniferous rainforest set among dramatic coastal mountains, deep-water fjords and bays. The underwater environment is so rich on the coast of British Columbia (BC) that the number of worthwhile dive sites is boundless. If so inclined, one could make a dive from any location along the shore of Vancouver Island, or the mainland across, and find a virtually pristine, wild, underwater seascape teeming with life.

However, the greatest concentration of diverse fish and invertebrate life and the most photogenic location is at God’s Pocket Marine Provincial Park, located 20km northwest of Port Hardy on the northern coast of Vancouver Island. Its 2,025 hectares encompass Hurst Island and Bell Island and the world-famous dive sites of Browning Wall, Seven Tree Island, Buttertart Reef and Hussar Point.

Vancouver Island is 456km long, 100km at its widest point and forms a formidable barrier to the force of the Pacific Ocean. The Alaska Current rushes towards the coast of British Columbia but is hindered by the sheer magnitude of the island, which funnels a vast volume of water (billions of litres twice a day) around the island and through the Inside Passage. Tides can run five metres or more.

Before you even put a toe into BC waters, you are aware of the richness of life. The landscape is framed by enormous snow-capped mountain ranges rising high upon the horizon, with the coastal coniferous rainforest – a part of the world’s largest temperate rainforest system – dominating the landscape as far as the eye can see. Bald eagles hunt fish in the waters below. Seabirds abound, with petrels, murrelets and auklets making BC their principal breeding habitat. Surface disturbances betray the presence of a variety of marine mammals: sea otters, sea lions, seals, dolphins, orcas and baleen whales. At the water’s edge on the shoreline, sea stars, anemones, and mussels cling to rocks of the intertidal zone.

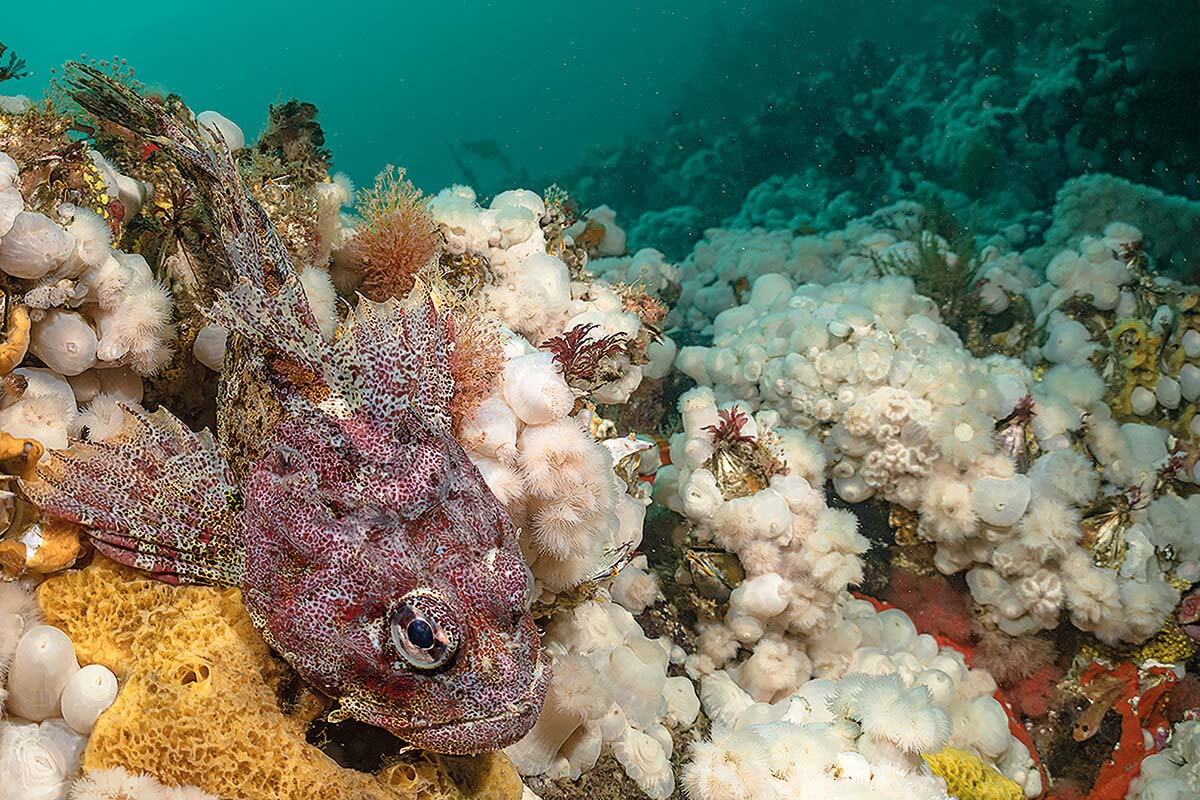

As enthralling as coastal BC’s natural world is at sea level, you are transported to another realm entirely as you submerge into the bracing 10.5°C water. Once you adjust to the chill in the water and the visibility of 6 to 25 metres (depending upon the season) and you first begin to take in the topography, trying to make sense of what you are seeing, you wonder if your eyes are deceiving you. The underwater seascape is otherworldly. Phantasmagorical.

A mind-boggling whiteness predominates, as if the rock face and bottom had been subject to a heavy snowfall or blizzard. It is a living thicket of white plumose sea anemones, cladding the crags, boulders, slopes and walls from near the surface and downward into the depths beyond sight. A smattering of bare rock outcrops and patches on the sheer walls are exposed, to affirm there is a solid geological structure underlying to which the anemones adhere. Sea anemones are in the phylum Cnidaria, in the same class as the stony corals of the tropics, and they share the coral’s polyp body form. A sack-like body clings to the bottom with a basal disc and then rises as a columnar trunk to an opening, an oral disc, where food enters and waste is expelled. The oral disc is ringed with threadlike organs that contain stinging nematocyst cells which the anemones use to defend themselves and capture prey passing within the reach of these tentacles. Anemones are sessile carnivores, ingesting passing invertebrates, zooplankton and larval fish, but they avoid consuming eggs, copepods and ostracods.

In the Pacific Northwest waters, there are two species of plumose anemone. Teeming in unimaginable numbers is the ubiquitous plumose or frilled anemone (Metridium senile), each the height and shape of a head of broccoli, although snowy white in colour. It is joined by the giant plumose anemone (Metridium farcimen) which can reach a metre in height, and while less numerous than its smaller relative, is conspicuous due to its towering tree-like form, crowned with lobe-like florets.

The giant plumose anemone is the world’s tallest polyp. The plumose anemones are found from surface waters down to 300 metres. They reproduce both sexually – via broadcast spawning with eggs or sperm emitted from the mouth – and asexually, by longitudinal binary fission, where a fragment of its basal disc is left behind as the anemone moves, leaving the fragment to form a new anemone. As the anemone has the ability and propensity to clone itself, could it be considered immortal? And even though they are individual polyps living communally, are they actually all one and the same? A clone that is the perfect copy of its progenitor is, arguably, the same animal, on a molecular level.

As you ponder these possibilities, you become aware of the various other lives that exist in association with, on, or around the anemones. Gaudily coloured Puget Sound king crabs amble about in their orange, purple and red armoured livery, looking for prey, such as barnacles, sea urchins and sea stars. These crabs grow to a maximum size of 30cm and have thick shells that only the most determined predator can penetrate.

Sea stars in a dazzling variety of sizes, shapes and colours are commonplace. Their number of arms vary by species. There are 43 species found in the Pacific Northwest. They range from the more-or-less standard five arms of the ochre sea star to the 24 arms of the sunflower sea star, which is, at one metre in diameter, the second-largest sea star in the world. There are also colourful sea cucumbers that snake through the anemone assemblies and boulders, while sea urchins are ever-present.

The grip strength which keeps the kelp steadfast against the force of the strong tidal currents is remarkable. Kelp species are, by nature, gregarious and form kelp beds of dozens to hundreds of individuals. This dense marine forest has a broad canopy at the surface, stipes tangling and untangling as currents ebb and flow, with a labyrinthine understory of long, lithe stipes rippling in the current, providing habitat, food and shelter to a universe of fish and invertebrates.

Fish are abundant, in a multitude of sizes and shapes. BC is home to approximately 410 species of marine fish. Some are bottom-dwellers, nestled among the plumose anemones for concealment from danger, others are formidable ambush predators awaiting the opportunity of an oblivious, close-passing prey to come within striking distance. Fish can be seen temporarily resting upon bare rock promontories or perched upon the varieties of colourful encrusting sponges that have somehow managed to displace the omnipresent sea anemones for their own bit of turf.

Approximately 300 species of sponge live in BC waters, all managing to utilise chemical defences to obtain a foothold among the anemones. Other fish patrol and defend boundaries they alone recognise among the rocks, clefts and caves of the craggy topography. Other species go about fish business higher in the water column or seek protection or prey among the giant kelp canopies.

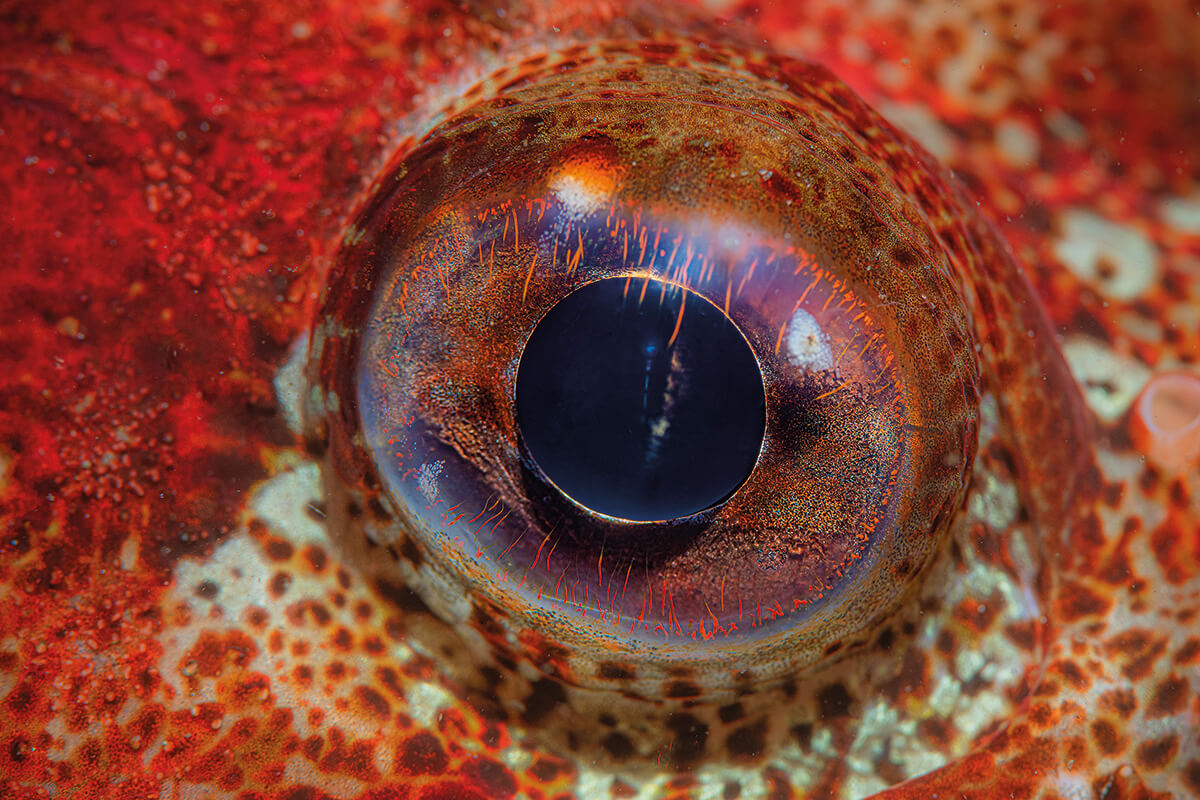

In these temperate waters, the fish population is dominated primarily by members of the scorpionfish family, one of the world’s largest fish families, with 65 genera and 450-plus species in tropical and temperate waters. In BC the rockfishes (Sebastinae), sculpins (Cottidae) and greenlings (Hexagrammidae) predominate. While it is common to think of temperate water fish as being in the autumn colour palette, in fact, there are numerous species that have dramatic colouration which would rival that of their distant tropical cousins.

The most diverse and varied species are the rockfish, exhibiting a wide variety of colours, patterns, shapes and sizes, yet all characterised by possessing venomous spines on their dorsal fins (as with tropical stonefish, scorpionfish and lionfish), large eyes and mouth, a compressed lower body, a jutting lower jaw, large size, slow growth, and their extreme longevity. They are usually solitary and territorial, tolerant of visiting divers, even curious. Rockfish are among the longest-living fish on Earth, with several species known to surpass 100 years of age (and a maximum reported age of 205 years for the rougheye rockfish).

Most species utilise internal fertilisation, and some species are ovoviviparous, while others lay their eggs in a gelatinous mass. They feed on shrimp, small fish, jellyfish, squid, crab, crab eggs, octopus, sea snails and worms. Thirty-six species of rockfish are found in BC waters.

When it comes to coloration, the greenlings rival the rockfish. They are large fish, accustomed to resting on the bottom, but can be very active predators. The rock greenling (Hexagrammos lagocephalus) stakes out a territory within the dynamic surge zone where eel grass and kelp form its preferred habitat. The male is striking with its bright red livery and inquisitive nature, and this 60cm fish has a lifespan of 11 years. The kelp greenlings are similarly sized, with the female exhibiting a stunning yellow coloration and the male a pale-blue, dotted with brilliant cyan spots.

The largest greenling is the ling cod, which reaches 114cm in length, can weigh 25 kilos, feeds upon fish, crustaceans and octopus, and has the demeanour of a tropical barracuda.

Sculpins are bottom-dwellers, masters of camouflage, and many species exhibit plate-like structures on the body. The largest and most frequently encountered species is the red Irish lord, a carnivorous, sit-and-wait predator, blending into its surroundings, using its colour-morphing ability as camouflage to conceal itself from its prey: crabs, fish and shrimp. No one knows the derivation of the name ‘red Irish lord’, which are ever-present on BC reefs, even if their camouflage often makes them difficult to see.

Grunt sculpins have a distinctive look that is cartoonish, as if cobbled together from parts of several other fish. Their large heads represent over half of their total body length, and feature a long, tapered snout, two bony ridges on top, and small cirri on the upper lip. They are the size of a golf ball and hop around on their pectoral fins, using mussel shells and abandoned barnacles as homes. The smaller and more cryptic species encountered are the eel-like gunnels (Pholidae), and the warbonnets (Stichaeidae).

But there are two marine animals found in BC waters that fascinate beyond all others: one vertebrate and one invertebrate. Both are crevice-dwelling cryptics but will often reward the patient with an audience. And these are the big-animal attractions of the Pacific Northwest.

The misnamed wolf eel (Anarrhichthys ocellatus) is not an eel. Wolf eels belong in the wolffish family (Anarhichadidae) and are the sole species representative in the Pacific Ocean, whereas the North Atlantic has four species. Wolf eels form long-lasting, monogamous pair bonds and have a life span exceeding 25 years. They grow to a length of 2.4m on a diet of mussels, clams, crustaceans, and their absolute favourite: sea urchins.

Wolf eels have strong, conical canine teeth and rows of rounded molars in each jaw, as well as a bony plate in the roof of their mouth allowing them to crush hard shells and sea urchin spines without damaging tissue. As adults, they are dark grey to grey-white, with freckled grey spots and develop a very large head with big fleshy lips. The females are smaller in length and a darker brownish-grey coloration.

Juveniles are bright orange, with a brown, mottled spot pattern, and as they grow, the orange fades and is replaced by a grey or olive mottled pattern. They may look fierce but are benign, often coming out of their lairs to investigate visiting divers. Some may call them ugly but truly they are one of the most charismatic fish one can encounter in any ocean.

The giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) is the largest species of octopus and may live up to five years, in which time it grows from a tiny paralarvae smaller than a grain of rice, to an adult, 45kg in weight and 6m from arm tip to arm tip. There are reports of giant Pacific octopus reaching 270kg and a 9m span. They are capable of changing colour from pale pink-brown to a reddish-brown, to deep crimson. Each of their eight arms has two rows of suckers, with 280 suckers per arm, or 2,240 in total. They are highly intelligent and prey upon crustaceans, with a particular fondness for crabs, bivalves, fish, small sharks and even, on occasion, seabirds. Octopus are primarily nocturnal hunters and spend much of the day hiding in crevices in the reef, but it is not uncommon to find them out and about. Their sheer size is staggering to witness, a true meeting with a powerful, intelligent alien being. The reefs of British Columbia are rich with octopuses’ gardens and the sight of a giant Pacific octopus gliding about the fields of plumose sea anemones is beyond your wildest dreams.

• Douglas dived with God’s Pocket Resort (www.godspocket.com) and is grateful for the assistance and guidance of two incredible dive guides, Tiare Boyes (www.tiarebuoys.com) and Suzie Hall. This feature would have been impossible without so much help from these fine guides. Thank you!