The ocean’s cleaning stations are one of nature’s most remarkable examples of how evolution finds solutions to life’s challenges

Words and photographs by Douglas David Seifert

Nature doesn’t have problems, only solutions. If you are a typical fish, you may have an array of extraordinary sensory systems, impressive navigation abilities, sustained swimming power or highly developed camouflage. Yet the one thing fish do not have is the ability for tactile manipulation of their world. As they have no hands or claws, when they have an itch, they cannot scratch themselves; when they have a parasite affixed to their tissue, they cannot easily dislodge it. Thus, without prehensile appendages to rid themselves of parasites, they have co-evolved a fascinating partnership with smaller fish and shrimp in a system of cleaner-client relations.

On reefs around the world, certain recognisable, micro-habitats known as ‘cleaning stations’ can be found. Cleaning stations are the preeminent example of mutualism in the sea. They are typically well-established, permanent, and constant in terms of location. They endure beyond fish lifespans. These cleaning stations are conducted by a specific fish species (one recent scientific paper estimates 208 fish species from 106 genera representing 36 families), or, in some cases, a handful of shrimp species (51 species from 11 genera representing six families thus far identified).

The cleaner fish or shrimp perform a daily, on-demand, non-partisan service of parasite and dead tissue removal from various kinds of visiting fish, depending upon geographic location and species of the ‘cleaner’. Some cleaners are part-time cleaners, augmenting their regular diet with the parasitic invertebrates they glean from host fishes; other cleaners are almost exclusively dependent upon the parasites carried by their neighbours for their dietary requirements.

More great reads from Douglas David Seifert

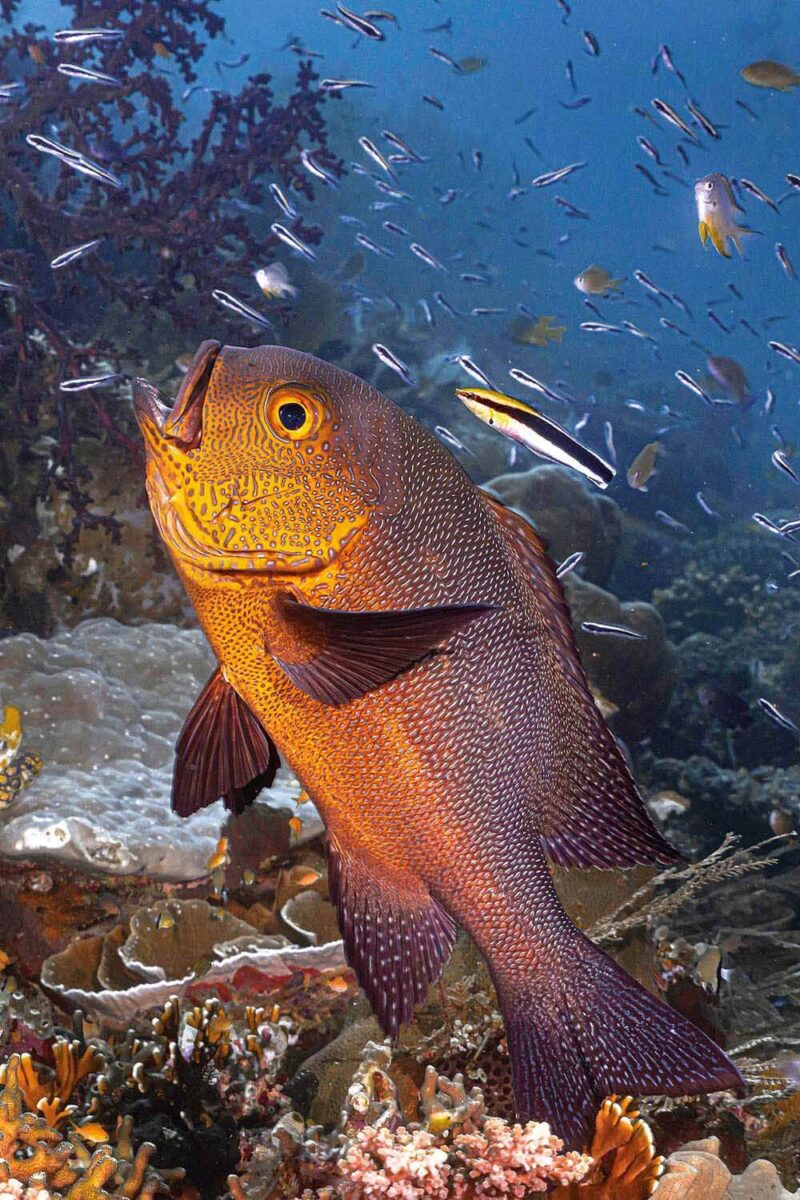

These ‘clients’ range from local reef residents to transient visitors, small reef fish (sometimes even smaller than the cleaner itself) to reef predators such as groupers, jacks, snappers and barracuda, to large pelagics, such as manta rays, sea turtles, ocean sunfish, or sharks.

An active cleaning station is obvious from the traffic and variety of fish species visiting the site, and even more obvious when the cleaning client is megafauna of large proportions. It is not uncommon to see various fish milling about an area, waiting for a cleaner wrasse or goby or shrimp to be available, and many client fish may make multiple visits daily, with a frequency observed to be between 12 and 144 times per day.

The parasite load of gnathiid isopods, copepods, and worms is infinite and provides a continual source of irritation for the infested clients and a continual buffet for the cleaners. In return for this service, the clients that are not herbivores or planktivores and are, in fact, by nature piscivores, somehow overcome their natural urges and remarkably do not eat the ‘cleaner’.

This is quixotically referred to as ‘reciprocal altruism.’

The most active cleaning stations are found adjacent to reef crests, at the peaks of bommies and pinnacles, and at select sites along a reef face sloping into deep water.

Cleaning stations are associated with rich biodiversity and abundant concentrations of fish populations; a popular one is indicative of a healthy reef. These reef pitstops attract all manner of fish life. Indeed, it is not uncommon to have predators lurking within sight of a cleaning station awaiting an unwary fish distracted by the frenetic activity or, perhaps, after its session, a bit too relaxed to resume its vigilance.

The most commonly encountered (and best studied) cleaning stations are those found throughout the Indo-Pacific Ocean and in the Red Sea which are serviced by the bluestreak cleaner wrasse (Labroides dimidiatus). They advertise their cleaning service through the combination of a highly visible colouration and a flamboyant behavioural display.

They exhibit an undulating dance of enticement as they hover in the water column above the coralline structures. Experiments have determined that their colouration of vibrant blue stripes bisected by a pronounced dark lateral line is universally recognised by other fish instinctively, as a cleaner.

Bluestreak cleaner wrasse live together primarily in male-dominant, male-female pairs, although the male may tolerate additional female partners in his territory. They work together, inspecting a client fish’s body surfaces, gill cavities and mouth, and consuming ectoparasites (bloodsucking gnathiid isopods, monogenean flatworms, and trematodes).

Occasionally, they also ‘cheat’ by taking diseased tissue, scales, and fish mucus, a painful departure from the anticipated parasite removal service the client fish bargained for. When a cleaner cheats, it may be punished by the client fish, either by being chased around the reef or, in the future, the fish will go elsewhere for cleaning.

When a client fish at a cleaning station is observed to twitch or jolt, the probable reason is an unanticipated nip of a cheating cleaner, a jarring sensation akin to having a scab unexpectedly ripped away.

Often, the cleaner will stimulate the client by tickling its body with their fins in an attempt to placate the aggrieved client. In experiments, cleaners prefer the high-calorie, energy-rich fish mucus to the protein-rich isopods, but they restrain themselves as best they can to make the cleaner system work.

It is believed that the cleaning behaviour of feeding upon parasites evolved from an original niche diet of feeding upon fish mucus and that parasite removal service had greater success for the species, thus refining the behaviour of modern-day cleaner wrasse.

Because most fish are incapable of removing parasites, the benefit of having another do so is evident. The cleaner gains a rich source of food that is brought to them and for which they do not have to expend energy foraging. A win-win situation.

Bluestreak cleaner wrasse have pincer-like canines designed for picking, and are selective feeders, choosing the largest of parasites and species that appeal to them the most. They have a short intestinal tract and lack a stomach. Therefore food passes through in less than four hours, a reason why an average cleaner wrasse consumes seven per cent of its body weight in parasites – some 1,200 gnathiid isopods – a day.

A cleaner wrasse’s day is non-stop, from dawn until dusk, with up to 2,300 client (and would-be client) interactions a day, often servicing more than 100 different species of fish, including large piscivores that refrain from eating them. In experiments, cleaner wrasse cleaning activity caused a 4.5- fold decrease in ectoparasite abundance after twelve hours.

A cleaning station is closed at night when most reef fish settle into nocturnal hideaways. It is at this time, when fish are hunkered down close to the bottom that the gnathiid isopods rise up from the substrate and attach themselves to the sleeping host fish. The isopods are parasitic only as juveniles, living on fish blood and plasma until they grow into free-living adults, no longer bloodsucking pests.

There are twenty or so species of cleaner wrasse engaged in cleaning station behaviours in the Indo-Pacific and the Red Sea. At cleaning stations regularly visited by reef manta rays (Mobula alfredi) in places such as the Maldives, Indonesia, Micronesia, Africa and other regions, bluestreak cleaner wrasse share the daunting task of cleaning a four-metre, 1,000kg ray with moon wrasse (Thalassoma lunare).

Competition is hardly a problem, due to the size of the client and the number of clients likely to visit over the course of a day. Because of the sheer amount of ectoparasites a manta can carry, and the magnitude the wrasses consume, the wrasses’ metabolism must be similarly hyperactive to that of hummingbirds.

These two wrasse species have also been observed to clean pelagic thresher sharks (Alopias pelagicus), silvertip sharks (Carcharhinus albimarginatus), and grey reef sharks (Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos).

In Hawaii, green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas) regularly visit cleaning stations where marine herbivores yellow tangs (Zebrasoma flavescens) and gold-ring surgeonfish (Ctenochaetus strigosus) remove algal growth from their shells and other body areas, as well as dead tissue and moulting skin.

In Indonesia, most notably off the islands of Bali and Alor, southern sunfish (Mola alexandrini) can seasonally be found at cleaning stations attended to by blacklip butterflyfish (Chaetodon kleinii) or bannerfish (Heniochus diphreutes) and occasionally by emperor angelfish (Pomacanthus imperator).

Sunfish are notorious for infestations of parasites, sixty species of which have been found on a single animal. In the Eastern Pacific, fishes that are non-specific cleaners perform cleaning duties to augment their normal diet: scalloped hammerhead sharks (Sphyrna lewini) are regularly groomed by shoals of blacknose butterflyfish (Johnrandallia nigrirostris) and passer’s angelfish (Holacanthus passer); at San Benedicto Island. Clarion angelfish supplement their feeding habits by performing parasite removal services for oceanic manta rays (Manta birostris).

In the Atlantic, gobies are the primary reef fish cleaners, with cleaner gobies (Gobiosoma genie) and neon gobies (Elacatinus oceanops) the main cleaners at stations associated with large sponges or coral heads, where gobies are more likely to be situated, in contrast to the free-swimming cleaner wrasses of the Indo-Pacific. Other Atlantic sometime cleaners are juvenile stage French angelfish (Pomacanthus paru) and grey angelfish (Pomacanthus arcuatus) and juvenile Spanish hogfish (Bodianus rufus).

Although parasitic isopods are invertebrate crustaceans, other crustacean species perform cleaning services consuming their parasitic brethren. In the Atlantic, the Pedersen shrimp (Ancylomenes pedersoni) perform a similar undulating dance to that practised by bluestreak cleaner wrasse of the Indo-Pacific, advertising their professional cleaning skills. They are secure in the mutualistic code of servicing predatory fish without being eaten. Scarlet cleaner shrimp (Lysmata amboinensis) can be seen busily attending to moray eels of many species throughout the Indo-Pacific, crawling all over the eels’ sinuous bodies and into their mouths with impunity.

Cleaning stations are fascinating places for fish-watching and a glimpse into the codes of animal behaviour. They are the most active sites on a reef, with only areas adjacent to strong current or provisioning sites to rival them for biomass, diversity and activity. They are a fish-watcher’s or photographer’s best opportunity to get close to otherwise flighty and cautious fish.