Words and pictures by Douglas David Seifert

You look around, into the smoky, blue-grey waters: visibility is pretty good, something approximating 20m horizontally, maybe more, hard to tell, because it is somewhat dim. You are trying to discern any shape or movement – anything at all – and all you see is… nothing. Your depth gauge reads ‘28m’ and a glance at your watch informs you that it is just after 6am – sunrise. The combination of these two pieces of information explains why the light is so subdued, even as you look upwards in the direction of the rising sun. You are diving at this remote place at dawn solely because then, and for a short time after, something very special can be seen with a predictable degree of reliability.

The scene illuminates itself incrementally as every minute the sun rises a notch higher above the horizon. Before you is a vista of a reef that is unremarkable, and, in fact, quite plain, bereft of points of interest, sparse on fish life, or any life at all. The divers are kneeling on the rubble on a nondescript plateau. It is made up of antediluvian limestone rock, and the well-worn skeletons of dead coral heads rubbed smooth by time. It has been laid flat partly by the unrelenting contact with carelessly tossed boat anchors and the daily collisions of clumsy scuba divers.

It is not a pretty seascape. In fact, it is quite ugly, like the aftermath of a natural disaster or war zone. There are a few fish and some rather worse-for-wear gorgonian sea fans and sea whips that look as if they have been through a storm. It’s true that major typhoons have devastated this region in the recent past, but this reef damage is too deep to have been caused by the fury of waves. It looks scoured, diseased, worn-out. A wasteland. Perhaps it was caused by the abuse of man or it may be that it was never pretty at all. Regardless, you think to yourself of all the rich, beautiful reefs of the Philippines archipelago, this dive site certainly is not one of them. And yet here you are – you came for one reason and one reason alone: to see a thresher shark.

Kneeling is unnatural for scuba diving where the golden rule is to remain neutrally buoyant and not make any unnecessary physical contact with the reef. But we do as we have been instructed in the pre-dive briefing. There is a mêlée of other divers – a dense cluster of bodies and activity. The dive guides check that everyone follows ‘The Rules’, which were covered in such detail during the pre-dive brief. They are the generally agreed upon code of conduct formulated by the local operators. The Rules have evolved to allow this rare marine wildlife interaction to proceed successfully both for the visitors and for the thresher sharks, which are the undoubted stars of the show.

From the mix of accents and languages heard at the dive shop and on the boat ride out to the site made in the pitch darkness of the predawn, the composition of the dive group is primarily European and Asian, with a smattering of Americans and Brits. There are more men than women, but not dramatically so. Most are young, late teens to late 20s; the majority are newly minted divers determined to tick off another check box on their personal bucket lists. GoPro cameras on long sticks are waved about as are a smattering of point-and-shoot still cameras. Another experience for their social media.

The assembled throng of divers aligns itself along a worn polypropylene rope. The line is suspended from metal rods spaced along the rocky plateau, set back 10m from the drop-off into the abyss. It runs for dozens of metres in either direction, forming a fragile but tangible boundary situated just below the waist level of an average-sized kneeling diver.

The open space in front of the line is where the action is expected to take place: a small rise of coral heads with a few fish flitting about, some sea whip branches and gorgonian sea fans providing a small vertical accent to a largely flat, horizontal vista. You recognise one species of the small fish swirling above the coral head – they are blue-streak cleaner wrasse (Labroides dimidiatus). Their role in the marine environment is to eat parasites and excise dead tissue from larger fish at cleaning stations. Another larger wrasse species catches your eye and you recognise it as a moon wrasse (Thalassoma lunare) and you recall they too perform cleaning functions, often on manta rays.

The water is full of bubbles from the other divers. You try to ignore their presence as you peer out into the blue for your objective. Then you hear the hollow tap of metal on metal. A dive guide, maybe yours, maybe from another boat (it’s getting crowded down here with more divers arriving), is rapping his tank with a metal clip. He is pointing into the blue-grey mid-water beyond the isolated coral head. Your eyes track in the direction to which he points and you discern movement amid the monochrome grey-blue sea. You see a shimmer of light as sunbeams piercing the water glint off the flanks of a large object moving towards you.

Your eyes and imagination struggle to make sense of what you are seeing: an elongated, wavy, sinuous ribbon, thin and flexible as an aluminium tape seems to be fluttering in the mid-water. You realise the object is approaching, not receding, and it is, in fact, the tail of a truly extraordinary animal. The tail propels the animal’s odd, torpedo-shaped body forward at a swift pace.

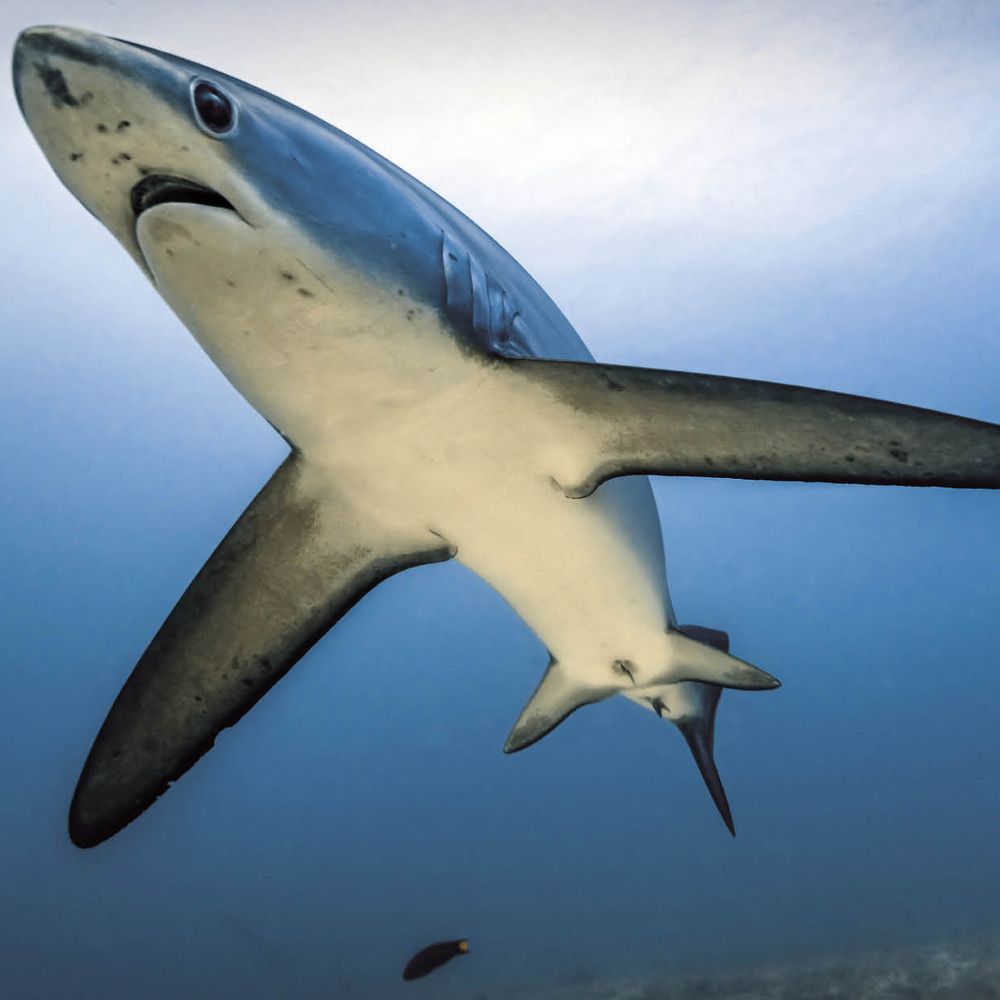

The scythe-like tail defines the animal: it constitutes nearly 50 per cent of the animal’s total length and it is mesmerising in the way it moves, not back and forth with the predictability of a metronome or rigid like an oar but instead, the tail oscillates fluidly and somewhat theatrically, in broad strokes, waving, twirling, swirling like the pennants of a Chinese acrobatic troupe. The tail is, more accurately, an elongated, asymmetrical caudal fin, and it is used not only for propulsion but also as an evolutionary adaptation to kill or stun prey. The tail can be used in the same fashion as a bullwhip, with the same ability to transfer great energy and speed to its tip with concussive force. Their prey is often small schooling fish, such as clupeids or sardines or other baitfish. A thresher shark flicks its tail into a fish school and stuns multiple small fish. It then turns back and devours them in a leisurely fashion. The body is fusiform, tapered on either end, with a conical head, a thick midsection, with the characteristic dorsal fin and long, elegant pectoral fins that instantly conjure the iconic body form of a shark, albeit an exotic one. Its body has an electric glow, glinting a gunmetal-to-bluish tint that catches the sun’s light rays and reflects them like the metal fuselage of a vintage fighter aircraft. On its underside there is a creamy white counter shading colour pattern. It has a relatively tiny mouth.

The shark’s eyes are enormous, needed for the deep-water domain where it spends the majority of its time. It stares straight through you as it approaches and passes.

You remain kneeling on the bottom, transfixed. The body, the tail, the great big eyes and the tiny mouth wholly capture your attention and remind you of nothing else in nature. Rather it brings to mind some creation by Disney or perhaps Hergé’s Adventures of Tintin cartoons.

The shark has risen from the depths as the subdued crepuscular light signals that the reef’s cleaning stations are open for business. There is no parasite removal at night because cleaner wrasses hide in reef crevices under cover of darkness to avoid potential predators and because the majority of their client fish are diurnal, not nocturnal. The thresher sharks leave their comfort zone of the dimly lit waters 700 to 200m below and make vertical migrations to visit these cleaning stations as dawn breaks. The cleaner wrasse and moon wrasse swarm over their parasite festooned bodies. The sharks return to the deeper water after their manicure. The depths protect them from most predators (such as larger sharks and orcas), and it is where they hunt their cephalopod prey during the day. They do rise to near surface depths at night to hunt small fish and surface-hunting cephalopods, and they are often caught on longline fishing tackle – hooked in the tail.

Monad Shoal is a flat-topped seamount with a meandering plateau at a depth of 15–33m and is approximately 1.5km in irregular length, the shoal rises from a 230m sea bottom and is located 8km from Malapascua, a 2.5km by 1km island on the northern tip of the island of Cebu, in the Visayas Sea of the Central Philippines. Monad has many cleaning stations situated along the eastern wall adjacent to deep water and hosts many colonies of blue-streak cleaner wrasse and other parasite-removing wrasse species.

It is one of the only reliable sites for divers to experience the thresher shark, although they can be encountered with some degree of frequency in the Southern Red Sea at two sites: the pinnacle near Elphinstone Reef and on the plateau at the south end of Big Brother Island. The thresher shark is occasionally seen in Alor, Indonesia; Pescador Island, Philippines; Osprey Reef, Great Barrier Reef; and at certain deep-water sites around the island of Bali, Indonesia.

This shark’s scientific name comes from the Greek Alopias (from Alopexias, meaning ‘fox’) and the animal is known by the French as requin renard (meaning fox), the Spanish as tiburón zorro (again, fox), and by the Germans as fuchshai (fox); as tiburón coludo in Mexico (slang for having a long tail) and lawihan in the Cebuano language of Cebu in the Philippines. The English and Americans use the common name thresher shark.

There are three known species of thresher sharks: the bigeye thresher (Alopias superciliosus), the slowest growing thresher reaching 4.6m; the common thresher (Alopias vulpinus), the largest species, reaching 6m in length for females, 5.5m for males; and the pelagic thresher (Alopias pelagicus) which is the only thresher shark that scuba divers are likely to encounter and is the smallest, maxing out at 3.3m. Without man’s interference, thresher sharks can be long-lived: pelagic thresher sharks are believed to live to be 29 years old and common threshers may even live 50 years.

Unfortunately, thresher sharks are highly prized by commercial fishermen and their populations have been critically depleted to virtual commercial extinction levels. The thresher shark populations in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans have been over harvested resulting in a population decline currently understood to be 70–80 per cent of their population numbers from the 1980s; a 99 per cent decline in the Mediterranean; and a 70–99 per cent decline in the Indian Ocean. An active fishery in the Lombok Strait off Bali is currently catching approximately 75 pelagic thresher sharks a day in the months of September and October; 90 per cent of the sharks are pregnant females. In an Indonesian fish market, the thresher shark’s fins bring US$30 and the meat US$1.50 per kilo. In Ecuador, 36 per cent of the sharks caught and brought to market in the shark-fishing town of Manta are thresher sharks.

Thresher sharks have relatively rapid growth rates with females growing faster and growing larger than males and reaching sexual maturity earlier than many other shark species. However, thresher sharks produce but two pups per litter per year for the pelagic thresher species and up to four pups per litter in the bigeye and common thresher species. The small number of offspring does not allow for a rapid comeback from depletion. Interestingly, thresher shark pups are relatively large when born – perfectly formed smaller versions of their parents. Pelagic thresher sharks are born between 1.5 and 1.9m in length! One such birth was witnessed at Monad Shoal in April, 2013.

The thresher shark is one of the few sharks that doesn’t respond to bait being used to attract them to a dive site. Just as with encountering scalloped hammerhead sharks (as is done most notably in the Eastern Pacific Ocean), all you can do is go where they are known to habituate and wait.

It is estimated that as many as 35,000 divers visit Monad Shoal each year to see the thresher sharks. They are brought by the four, large dive operations on Malapascua, some smaller seasonal operators and the peripatetic visits of liveaboard dive vessels.

A thresher shark dive currently costs the equivalent of US $27 per diver, per trip, which amounts to an aggregate value to the dive operators in direct fees alone of more than US $1,000,000 annually. And this does not take into account the substantially larger value of the connected tourist activity for the community of Malapascua (a small island home to 4,000 residents), for Cebu and for the Philippines as a whole. The indirect benefit is several millions of dollars per year to the local economy and a significant sum of money being spent in the rest of the Philippines.

And the sharks benefit as well. They now have legal protection, and ostensibly it is illegal to catch them or kill them in the area. There are other types of reef diving and other dive sites to be enjoyed at Malapascua beyond the unique experience with thresher sharks at Monad Shoal. But the reality is the reefs are extensively damaged and below standards due to relentless dynamite blast fishing in the past and continuing dynamite fishing today. The sad fact is on an hour-long dive, the muffled sound of an explosion heard underwater is a certainty, not the exception. Although dynamite blast fishing is supposed to be illegal, it is rumoured that the spouse of a highly placed government official owns a dynamite factory. Enforcement is largely a matter of talk, not action. There are macro subjects to delight any diver: plentiful nudibranchs, ghost pipefish, cuttlefish, frogfish, starfish everywhere, and a really good mandarinfish dive. But for glorious coral reefs, one has to visit another part of the Philippines.

It is debatable if the sharks have a choice about whether to perform their cleaning station ablutions with a gaggle of bubble-blowing onlookers. Certainly the regular and constant presence of scuba divers has altered the behaviour of the sharks in a way beneficial to human beings. The sharks’ natural wariness has been tempered by non-threatening experiences with relatively courteous human behaviour.

The code of conduct that the majority of operators abide by serves to balance the needs of the animals with the desires of the tourists. Most of The Rules make perfect sense: divers are to stay behind the rope line; to settle down and not create commotion when the sharks appear; to breathe slowly, minimise breathing or to slightly hold your breath when a shark is on a direct approach; and the use of lights or strobe flash photography is strictly forbidden. The rationale for the latter point being animals with big eyes will be discomforted by bright lights – which makes sense on the face of it, but has questionable scientific validity – especially as the thresher sharks are known to breach in bright sunlight without adverse effects.

You watch a thresher shark approach to within a few metres and turn away, circling back slowly to the frenetic coterie of cleaner fish. As you watch it turn, a movement beyond catches your eye and a second thresher shark appears. The cleaning stations are popular. Multiple sharks being cleaned at the same station at the same time are not uncommon. You realise you are not bothered by the crowd of divers to either side of you along the rope line. They are enjoying the moment, just as you are. •

• Douglas dived in Malapascua with Sea-Explorers Diving Center. Special thanks to dive guide extraordinaire Tongy (Tong Abyss Dayday). In the process of making these natural light only images, Douglas was stung in the knee by an inimicus scorpionfish that was buried in the rubble underneath the rope line. Not recommended.