Exploring the vibrant coral reefs, many wrecks and conservation programmes of the Florida Keys and their exceptional scuba diving

Words and photographs by Raymond Wennekes

Stretching in a gentle arch as it loops down towards Cuba, the coral archipelago of the Florida Keys forms the southernmost part of the USA. The Overseas Highway, starting 20km (12.4m) south of Miami, strings together a host of keys, some no more than spits of sand, and others well-established holiday destinations.

Crossing the Seven Mile Bridge, the iconic road leads right down to the Lower Keys, but takes you far further than its 182km (113m) route, transporting you back in time to where Hemingway fished for marlin and wrote his best novels, where rumrunners dodged prohibition; and even further back, when pirates and privateers harried Spanish galleons.

In some ways, this romantic chain of islands may well have seen better times. Many of the big fish and lots of the smaller ones have long gone. The coral reefs have suffered from disease, pollution and now climate pressures, but are proving remarkably resilient in places. And I doubt whether Hemingway would have found the modern boutique hotels to his taste. However, it still has its unique charms and offers some great diving, with a fascinating trail of wrecks to explore and some important marine conservation projects to discover.

Diving for the first time in the Florida Keys, I immediately noticed the water to be crystal-clear, a property attributed to several factors. The absence of major rivers flowing into the Keys means sedimentary run-off is minimal, allowing the relatively shallow water to maintain its remarkable clarity.

With depths ranging from just a few metres to around 20m, sunlight can easily penetrate the water, illuminating the vibrant coral reefs and marine life below. The extensive network of coral reefs surrounding the Keys also plays a crucial role. The third-largest barrier reef system in the world, it filters and purifies the water, and helps maintain the marine environment.

The Florida Keys’ coral reefs are home to some 45 species of stony corals, 35 soft corals and more than 500 species of fish, five of the seven species of sea turtle, and a variety of ray and shark species. Equally important are the seagrass beds bordering the Keys’ shores, which serve not only as grazing grounds for the gentle, herbivorous manatees that are frequently spotted in the area, but also as nurseries for juvenile fish, providing them with a safe environment for growing before going into deeper waters.

The coastal mangrove forests also play an essential role for many species, acting as a buffer against storms and providing a crucial nursery habitat for fish and invertebrates, while helping to filter pollutants from the water, contributing to the overall health of the ecosystem.

As with much of the world’s coral reef systems, however, the biodiversity of the Florida Keys is fragile. The first sanctuary, John Pennekamp Coral Reef State Park, was established as early as 1960 in order to address the deteriorating reefs, but in some respects they have provided only a temporary stopgap.

Florida’s population at the time of the Pennekamp park’s creation was just over five million people; by the turn of the century that figure had more than tripled, and stands at more than 22 million as of 2022. With more people came more tourists – now equivalent to the entire state population of 1960s Florida – and with them, more boats, more divers and more recreational fishing.

Additional protected areas were established during the 1970s, and 80s, but oil drilling, chemical pollution and deteriorating water quality continued to take their toll. The final straw came in 1989, when the freighter MV Elpis ran aground, destroying some 3,000 square miles of reef in the process. George HW Bush signed the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary into law in 1990 almost as a direct result.

Some estimates suggest that over the last century, as much as 90 per cent of Florida’s coral has been lost, with an increase in both commercial and recreational fishing simultaneously depleting the local fish stocks. A study from the University of Miami and NOAA found some species had waned to as little as five per cent of their sustainable population levels. Florida’s ‘red tide’ – a natural bloom of toxic algae significantly enhanced by agricultural run-off – has regularly impeded recovery, and an insipid spread of stony coral tissue-loss disease (SCTLD) since 2014 has killed off more of an already overstressed reef.

The establishment of special areas of conservation within the Marine Sanctuary, however, appear to be having an effect. Around 550sq km of the park’s 9,900sq km total area are dedicated ‘no-take’ zones, and NOAA’s 2022 report found that there has been an increase in both the populations of non-targeted fish species, and their physical size.

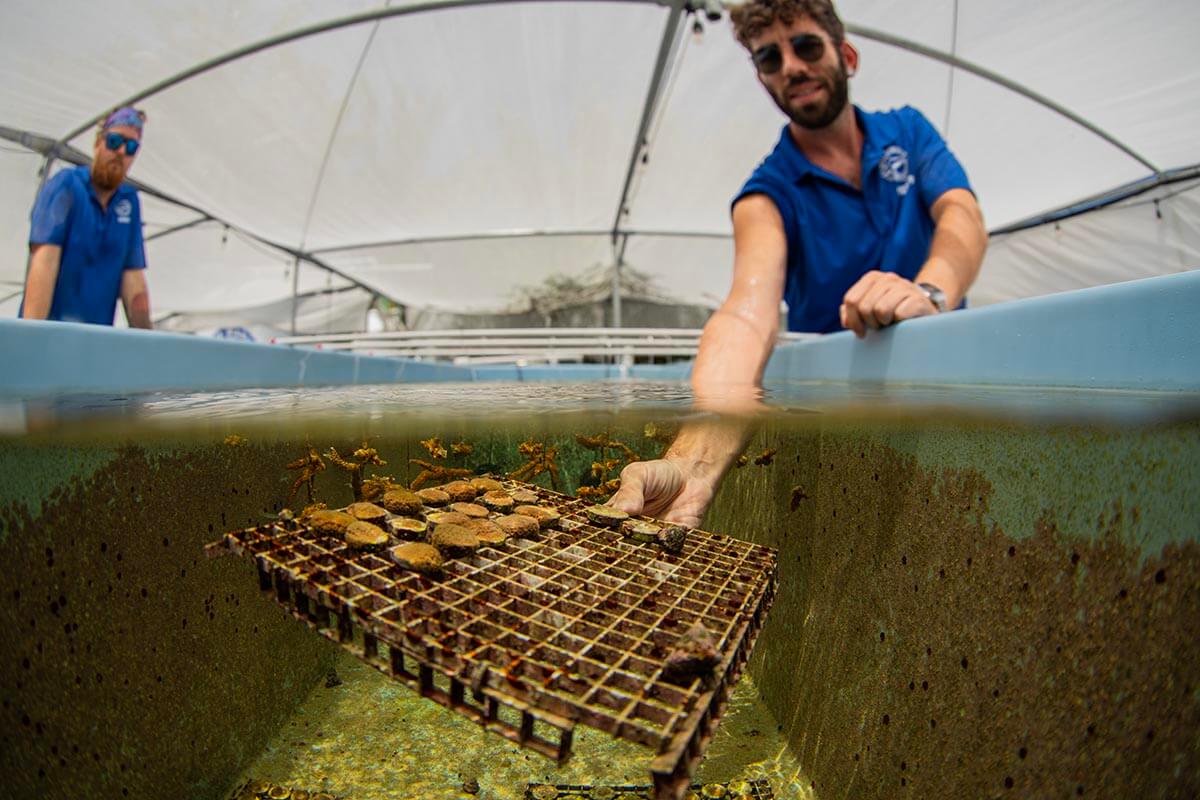

Coral conservation initiatives, as exemplified by the Mote Marine Coral Nursery in Islamorada, are also playing a vital role in coral reef restoration. Established by the Mote Marine Laboratory, the nursery’s focus is on cultivating the most observably resilient coral before outplanting them back into the reef, heightening their chances of survival.

Showcasing its very much ‘hands-on’ approach, Mote Marine Coral Nursery offers tours for visitors and allows divers to take part in coral reef restoration dives, which we experienced during our visit. ‘We aim to generate new research findings,’ said Elli, our guide during the tour.

‘While it’s gratifying to stimulate coral growth and artificially reproduce them, it’s even more crucial that we find ways to adapt our corals to the ongoing ocean warming, as the temperature of the ocean will rise regardless of our local efforts. That’s why we’re also conducting genetic research to make our corals more resilient to warmer waters.’

The urgency of these efforts became painfully evident a few weeks after our visit, as the Florida Keys witnessed record-breaking seawater temperatures, which caused a widespread coral bleaching event. Prolonged exposure to warmer waters prompts corals to expel their colourful symbiotic algae, making them susceptible to disease and hindering their ability to recover. The distressing phenomenon left the lively coral colonies we saw during our visit pale and weakened.

The bleaching is undoubtedly a result of the recent El Niño, which forms over the central and eastern Pacific Ocean but affects oceans all around the world and caused the water to rise to record-breaking temperatures in the South of Florida. In July 2023, water temperatures throughout the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean Sea rose approximately 1-3°C (2-4.5°F) above the average of 28-30°C (82.4-86°F) for the time of year.

El Niño not only elevated water temperatures but also led to a prolonged period of calmness, during which the absence

of wave action caused the shallow waters of Florida Bay and the Gulf of Mexico to become excessively warm. Key Largo, being the largest land mass, fared better than most, but corals on inner reefs like Horseshoe Reef and Banana Reef experienced notable bleaching. Areas on the outer reefs,which benefit from a better inflow from the Gulf Stream, however, showed more resilience.

Just after my visit to the Florida Keys, I talked to renowned underwater photographer and publisher of many articles about diving the Florida Keys, Stephen Frink. He believes it is inevitable that there will be substantial coral mortality across the Florida Keys, particularly among the most affected elkhorn and fire corals and especially in the south, where the islands are smaller, and the channels allow for greater tidal flow.

The fish populations appear, for now, to be relatively stable. It seems that some migrated to deeper waters during the warm period, but once the temperature dropped, and then continued to decrease, the fish returned. There is hope, however: small blocks of coral remain alive among the dead reefs, adding weight to the essential nature of work such as Mote Marine’s, whose staff have been relocating living corals to onshore labs to wait out the heatwave.

Reports from Florida also suggest that the worst of the damage is mostly confined to the shallower reefs, whereas the deeper reefs, including those that are home to the wrecks of the Florida Keys National Marine Sanctuary Shipwreck Trail, have remained relatively unscathed.

The nine wrecks that make up the Shipwreck Trail – four of which are also included in the official Florida Keys ‘Wreck Trek’ (see page 40) – are a mixture of both accidentally and intentionally sunk ships – and more than one that sank accidentally while waiting to be sunk intentionally.

Time meant we couldn’t dive all nine, but the Vandenberg especially did not disappoint. One of the largest ships ever sunk as an artificial reef, the Vandenberg was scuttled in 2009, 11km (7m) off the coast of Key West, with the intention of relieving pressure from divers on the reefs closer to shore – although its difficult to say if this goal was ultimately achieved, as the local dive shop owners I spoke to said the Vandenberg actually caused even more tourists to come to the Keys to dive the wreck and, by association, the local reefs.

Originally known as the USS General Harry Taylor, Vandenberg was a naval transport ship that played a vital role in various military operations. Commissioned in 1944 during the Second World War, she served as a transport vessel for troops during the Korean and Vietnam Wars, before being transferred to the Maritime Administration where she was used for training exercises.

Today, the the wreck of the Vandenberg lies in around 55m of water at its deepest point, with its main deck at around 30m. It is a colossal ship, at 150m in length, and would take a number of dives to explore in full. Schools of fish swarm around the ship, goliath groupers, barracuda and moray eels among the larger species; and peering over the railing, divers might see bull sharks and sandbar sharks patrolling around the hull.

Although the long-term impact of the recent bleaching event will not be known for some time, there is much work being done to revitalise the reefs of the Florida Keys, and much for visiting to see while that work takes place, including joining in with the restoration dives.

The Keys may not be the ideal destination for hardcore divers who need to do three or four dives a day, every day, as most of the operators limit themselves to two dives – a deep wreck dive followed by a shallow reef dive – per day. There is, however, something here to suit all levels of divers, and as an underwater photographer, I had the time of my life in both the deeper wreck dives, and during the shallow reef dives with the vibrant corals, sun rays and the company of a casually passing turtle every now and then.

It also has to be said that for those who want to enjoy activities beyond diving (this is the home of Disney, after all) and also enjoy some laid-back topside atmosphere, delicious restaurants, and experience the rich history of their surroundings, the Florida Keys is combination that will not disappoint.

FACT BOX

Diving is year-round with average water temperatures ranging from 23°C (73°F) in January to 30°C (83°F) in August; expect to pay around £90 + taxes for a two-dive day (equipment extra). Return economy flights to Miami from the UK are priced between around £650 in the winter and £1,100 during the summer peak.

For more information visit www.fla-keys.co.uk or www.fla-keys.com outside of the UK.

Raymond Wennekes is an award-winning Dutch underwater photographer and DIVE Featured Photographer Find more from Raymond on his website www.raymondwennekes.com, and Instagram @raymondwennekes

More great reads from our Magazine…

- Battle of the Colours – the mating ritual of giant cuttlefish

- Mexico’s Manatees – the Sirens of the Caribbean

- DIVE’s Big Shot Kaleidoscope – the winners!

- How the Marine Megafauna Foundation makes sustainability sustainable

- Over & Under – the unique effects of modified digital lenses underwater