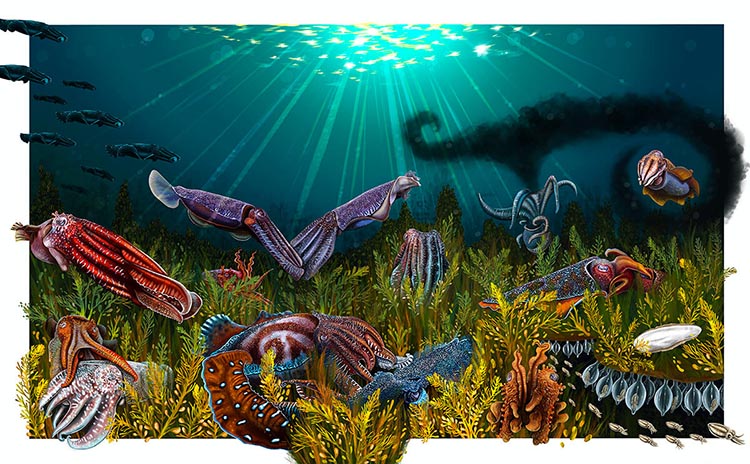

One of nature’s greatest spectacles, the final mating rituals of the giant cuttlefish, takes place on the reefs of South Australia

Words, photographs & illustration by Francesca Page

Immersed within the frigid embrace of the South Australian waters, I find myself gasping as the ocean strips away my warmth. I descend into a realm below, a world teeming with creatures that seem to belong to another dimension. As I surrender to the cold, a mesmerising spectacle unfolds – a showdown of hues as vibrant as they are enchanting. Let the battle of the colours begin!

Enveloped within emerald and marigold shades, I was surrounded by a bustling amphitheatre of giant cuttlefish, with the males in a contest for the attention of the females hiding in the seaweed below. My eyes struggled to grasp what was going on, even though this is an event I had researched and had longed to witness for years. At last, I hovered within a living scene straight from a David Attenborough documentary.

During the winter months in South Australia, between the shallow waters of Fitzgerald Bay and False Bay near Whyalla, this coastline hosts one of the world’s most unique and spectacular wildlife events. From May until August each year, more than 250,000 giant cuttlefish migrate to the cold and rocky coastline to breed and then perish. At the heart of the Spencer Gulf, with perfectly balanced salinity levels and an abundance of large, overhanging south-facing boulders, these are the ideal breeding grounds for these alien-like creatures.

The giant cuttlefish, recognised as ‘Yaryardloo’ by the Barngarla people – the Indigenous landowners – plays a crucial role in signalling the shifts of seasons. Cuttlefish await the water temperature to dip below 16 degrees Celsius before springing into action.

As my partner and I pull into the gravel car park at Point Lowly, our vehicle laden with scuba gear and camping essentials, we’re greeted by the sunrise illuminating our playground for the coming week. While we prepare, squeezing into layers of thick neoprene and adjusting our cameras for the dive, the car park starts filling up with fellow thrill-seekers. A local diver, his face beaming with enthusiasm, strolls over: ‘G’day! You folks picked the perfect week for a cuttlefish dive.’ Intrigued, I ask: ‘What’s so special about this week?’ He replies, pointing at our camera gear: ‘No southerly winds in the forecast for at least a week, only northerlies, so great vis for your shots.’

According to him, the prime time to encounter cuttlefish in all their glory begins in early June, when both favourable weather conditions, and their population i sreaching its peak. He has lived and dived here his whole life and generously gives us the ‘secret sauce’ to diving this dive site and how to get the most out of the event.

Thousands of cuttlefish migrate to this narrow coastal stretch due to its ideal conditions. The south-facing rocks provide perfect shelter for the cuttlefish to lay their tear-shaped eggs. With cold, brackish waters and a scarcity of predators, this spot is the ideal breeding ground. We gear up and slowly make our way down a narrow path, nimbly stepping from rock to rock, eager to get into the water to release the heavy load from our backs.

Taking a deep breath we plunged into the chilling waters for the first of many extraordinary dives in the week ahead. Camouflaging myself in the seaweed, I slowly come to the realisation that the cuttlefish are engrossed in their own world of courtship, seemingly indifferent to our presence.

Glancing at my partner, who was captivated with filming the mating rituals, I couldn’t help but chuckle. He’s so focused on his camera that he remains oblivious to the crowd he has attracted. Some used him as a shield, others as a resting post, some were fascinated by his video lights.

Males significantly outnumber females, sometimes reaching an astonishing 11 males to one female. This gender ratio fuels intense competition. Even with numerous suitors, females reject up to 70 per cent of advances, while still mating with multiple males. This backdrop sets the stage for an array of mating behaviours, each male trying to outshine the other to secure their chance. The more impressive the display, the greater their odds of winning over the female.

I watch two males eyeing each other up. They start an elaborate colour and shape-shifting show paired with intimidating skin displays. The battle commences! It felt as if I had entered a well-rehearsed stage show in London’s West End. All the males dressed up in the most colourful and elaborate costumes, putting on the performance of their life – and for some, their last.

Intricate dances of courtship unfold among the males, as they whirl around each other, flattering their form to appear larger. The spectacle intensifies as their bodies pulsate with a kaleidoscope of white and orange swirls. One male, engrossed by his reflection in my camera’s dome, mistook it for a rival. He began to reach out with his large arms, pushing his body against my camera, almost as if saying: ‘Back off, she’s mine!’

At one point he got so close to my camera that no photos could be taken; instead, I watched on, in awe.

Giant cuttlefish live for between one and two years and their death comes soon after a single cycle of mating and egg-laying. In the relentless contest for attention, the larger males parade their impressive size and colours trying to outshine each other, but this hormone-fuelled dance sometimes gets the better of them. In this courtship, size doesn’t always matter, and some of the smaller males, some only three months old, have mastered a crafty strategy: they are known as the ‘sneakers’.

These clever creatures masquerade as females, altering their colours and adopting a female form by retracting their tentacles. When the larger males are distracted, the ‘sneakers’ stealthily slip in, evading notice to swiftly mate with the female, right under the very snouts of the larger males above. This cunning crossdressing tactic proves remarkably fruitful, as the ‘sneakers’ have a 60 per cent mating success rate.

This was undeniably one of the dive’s highlights for me. Having witnessed this behaviour on Blue Planet, seeing these incredibly clever creatures in action is an unforgettable experience. In a mesmerising dance, cuttlefish undertake a unique mating ritual. They entwine their eight arms and two tentacles, forging an intimate head-to-head connection. The males then delicately transfer their sperm packets into the female’s mouth, fertilising her eggs.

The female then gently lays her tear-shaped eggs beneath the protective shelter of rocky ledges at depths of one to five metres, awaiting their transformation over the span of three to five months.

It is believed that they congregate here in such large numbers because it is the only area in the vicinity with rocky ledges suitable for egg laying and has the

perfect ratio of fresh to salt water. The area was almost destroyed by commercial fishing. In the 1990s the giant cuttlefish were nearly wiped out due to being overfished. In the space of three weeks, 38 boats caught 270 tonnes of giant cuttlefish. In the years following, their population dwindled to next to nothing.

However, following pressure from conservation groups, a permanent ban on fishing for giant cuttlefish has been put in place in the area, allowing them to return to healthy numbers. Now, instead of fishing them, we dive with them to enjoy their beauty and wonder.

This conservation triumph is a testament to the resilience of nature herself, showing that when we educate others and protect these vital ecosystems and marine life, Mother Nature can stage a remarkable comeback. As my week of diving in these cold and colourful waters comes to an end, I reflect on the extraordinary moments shared with these clever creatures. I’ve witnessed nature’s wonder and resilience first-hand in this underwater theatre of colourful dances and cunning strategies.

As I resurface from this captivating world, one truth remains clear; with the right conservation effort and education, we can turn back time and allow these wild places to thrive again. This isn’t a goodbye but ‘See you next year’, as I shall be back to witness the battle of the colours once more.

Find more of Francesca’s beautiful artwork at www.francescapageart.com and Instagram @francescaapage

More great reads from our Magazine…

- Mexico’s Manatees – the Sirens of the Caribbean

- DIVE’s Big Shot Kaleidoscope – the winners!

- How the Marine Megafauna Foundation makes sustainability sustainable

- Scuba diving Curaçao – a Caribbean gem

- Over & Under – the unique effects of modified digital lenses underwater