This poignant and challenging film is a fitting tribute to filmmaker Rob Stewart who died in a diving incident before it was completed

It makes you angry – extremely. It makes you sad – desperately. And, Rob Stewart’s third and last film, Sharkwater Extinction, also manages to leave you feeling empowered and keen to keep his fight going.

This is no mean feat for a campaigning documentary whose 37-year-old star, director and driving force was killed two years before the film’s release in a tragic diving incident.

It must have appeared to be an impossible job to pull together the at times stunning footage that Stewart had made about sharks and our awful exploitation of them before his death and turn it into a coherent, meaningful film. But the team behind the production of Sharkwater Extinction has succeeded and managed to avoid it becoming too mawkish or cheaply sentimental.

That’s not to say that it isn’t highly emotionally charged. There are moments when it is difficult to watch, such as the sequence of Stewart kitting up for his last dive. The camera lingers on his face. In close-up you see the apprehension we probably all feel the moments before we enter the water, but here it is poignant, nearly unbearable, as we know the outcome of this 65m-deep, rebreather dive.

When Stewart with his buddy and rebreather instructor Peter Sotis surfaced after their third dive of the day to the wreck of the Queen of Nassau in the Florida Keys, Sotis lost consciousness. Stewart seemed okay. As the crew retrieved Sotis from the water, Stewart disappeared. His body was found three days later. The autopsy says he drowned suffering from acute hypoxia on the surface – that is a lack of oxygen.

The latter part of the film, not only tells the story of his death, it pays tribute to Stewart’s remarkable career and legacy.

As a young Canadian dive instructor, underwater photographer and marine biologist, Stewart had been shocked to see the impact of long-line fishing in the Galápagos Islands and decided to make a film about the global plight of sharks. Four years later that became Sharkwater which was released in 2007 and has since been viewed by more than 125 million people and garnered 70 international awards.

That was followed by Revolution in 2013 which focussed on carbon emissions, particularly the impact they are having on the oceans through sea warming and acidification. There was something about the determined but humble way he told his stories that connected. He was charming, photogenic and passionate. He encouraged others and mentored key figures such as Australian filmmaker and activist Madison Stewart (aka Shark Girl and no relation) in the growing campaign to save our oceans from the threats of over-exploitation and global warming.

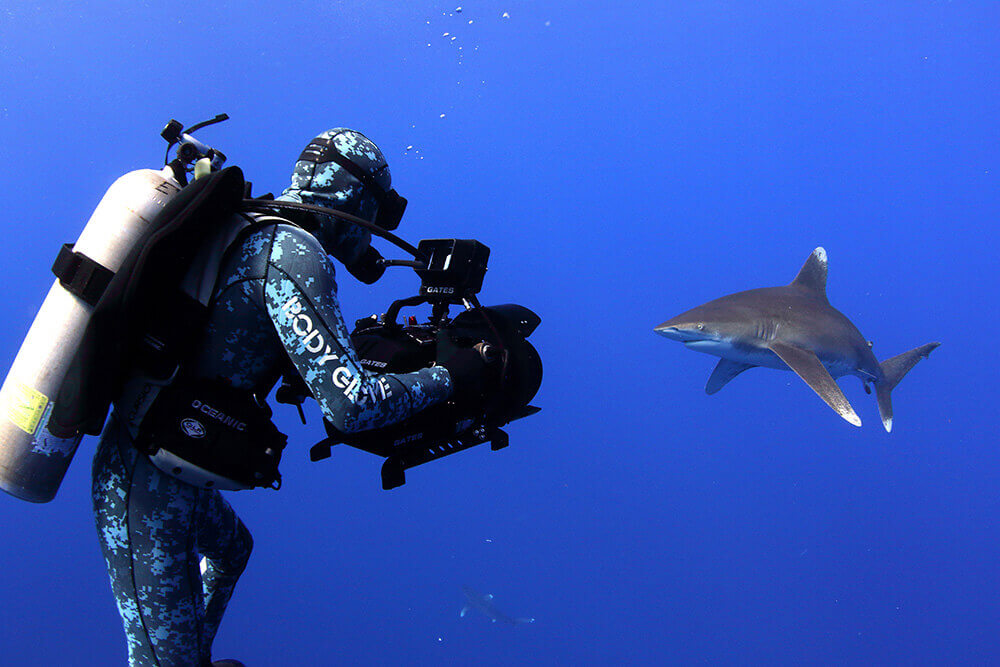

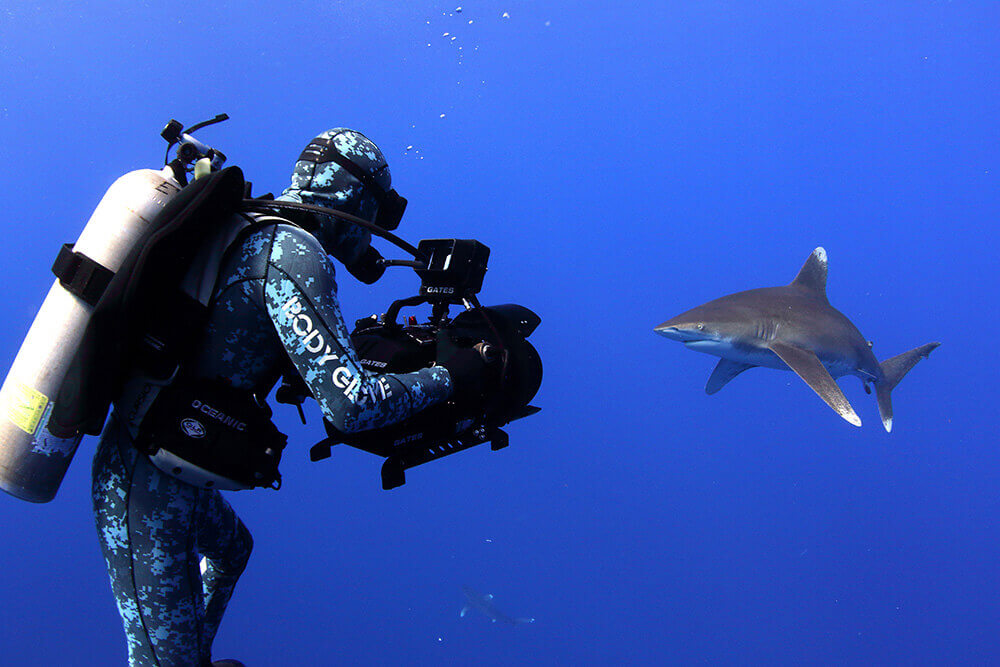

The first part of Sharkwater Extinction shows Stewart in action. High-quality, guerilla filmmaking, tracking the perpetrators of the mass destruction of sharks across the globe. As many as 150 million sharks are killed each year in a relentless pursuit of profit.

His drone finds a clear patch of roofing covering a dock in Costa Rica and we zoom down to see the hundreds of fins stacked underneath. That is just after we hear the bluff Louis Guillermo Solís, who was the country’s president at the time, telling Stewart at a press conference that they have made finning illegal and were doing everything possible to enforce the law. A local activist also tells us that Solís was responsible for tearing up a raft of environmental and fisheries regulations on coming to power in 2014.

We see Stewart charm his way onto a ship moored in Capo Verde off the African west coast and persuade the Taiwanese crew to boastfully show us their freezer hold packed with thousands of the mutilated corpses of blue sharks already stripped of their fins and destined for some unknown food or cosmetic factory.

We dive with Stewart just off Los Angeles at dawn when he finds a thresher shark slowly dying in a now illegal gill net. As he surfaces we see the irate fishermen firing multiple shotgun rounds at the dive boat as they quickly speed away.

One of the most shocking sequences is when he and Madison Stewart talk their way onto a leisure shark fishing boat out of Miami. They give the preening skipper more than enough rope to hang himself with as he boasts of killing more than 50,000 sharks for fun. But there is little time to mock his vanity as a paying angler hooks a scalloped hammerhead. As the skipper explains that most hammerheads die even if you quickly release them back into the water after taking a quick selfie on the deck, they slip into the water and film the sordid process of the shark being reeled in.

Back on board, Madison is clearly very upset. An interesting aside I discovered after seeing the film is that Madison befriended the skipper’s children, taught them to dive and they now support the campaign to protect sharks. There is always hope!

The film threads a number of these episodes into a powerful broadside against the obscenity of shark fishing and makes its case clearly and with plenty of impact. However, it does leave a stack of questions unanswered.

I wanted to know the name of the Costa Rican businessman that has built up a sinister empire on the back of illegal shark fishing. While I applauded Stewart and a friendly academic testing a variety of supermarket products to reveal shark DNA, I wanted more detail about exactly what they discovered and the brand names of the pet foods, cosmetics and fast foods. Obviously, it is important to establish that shark finning can only explain about half of the total take of sharks from our oceans. But I wanted to know far more about the supply chain around shark meat.

But I’m probably missing the point. There are always more questions to ask, more horrors to reveal, more battles to be won. But Stewart could never answer them all. And, as he says himself during the film, the point is to make us all ‘heroes’ wanting to take on the struggles that must be won if want to preserve a planet worth living on. And this film surely does that – what better tribute could there be to a true ocean hero!