Hard coral cover across the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) has declined sharply from its previous record high, according to the latest Long-Term Monitoring Program (LTMP) report from the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS).

The decline was largely driven by heat stress following the mass bleaching events of 2024 – the fifth since 2016 – but also by the impacts of cyclones and crown-of-thorns starfish (CoTS) outbreaks.

Despite the sharp reduction, however, coral cover across the Northern and Central parts of the Great Barrier Reef remained above the long-term average, although coral on the Southern GBR dipped 2.4 per cent below the regional long-term average.

Related articles

AIMS Long-Term Monitoring Programme leader Dr Mike Emslie said the effects of the losses were cushioned by the record high levels before the bleaching, but the rapid changes in cover indicated the reef has been under ‘severe cumulative pressure’ in recent years.

‘This year’s record losses in hard coral cover came off a high base, thanks to the record high of recent years,’ said Dr Emslie.

‘We are now seeing increased volatility in the levels of hard coral cover. This is a phenomenon that emerged over the last 15 years and points to an ecosystem under stress.

‘We have seen coral cover oscillate between record lows and record highs in a relatively short amount of time, where previously such fluctuations were moderate.

‘Coral cover now sits near the long-term average in each region. While the Great Barrier Reef is in comparatively better condition than many other coral reefs in the world following the global mass coral bleaching event, the impacts were serious.’

Of the 124 individual reefs that were surveyed for the 2025 LTMP report (of approximately 3,000 that make up the GBR), two were found to have less than 10 per cent hard coral cover; 77 had coral cover between 10-30 per cent; 33 reefs had cover between 30-50 per cent; ten had cover between 50-75 per cent’ and two were measured as having greater than 75 per cent cover.

Of all the reefs surveyed, 48 per cent underwent a decline in their percentage of coral cover, 42 per cent showed no net change, and 10 per cent had an increase.

Reefs with stable or increasing coral cover were predominantly located in the Central GBR.

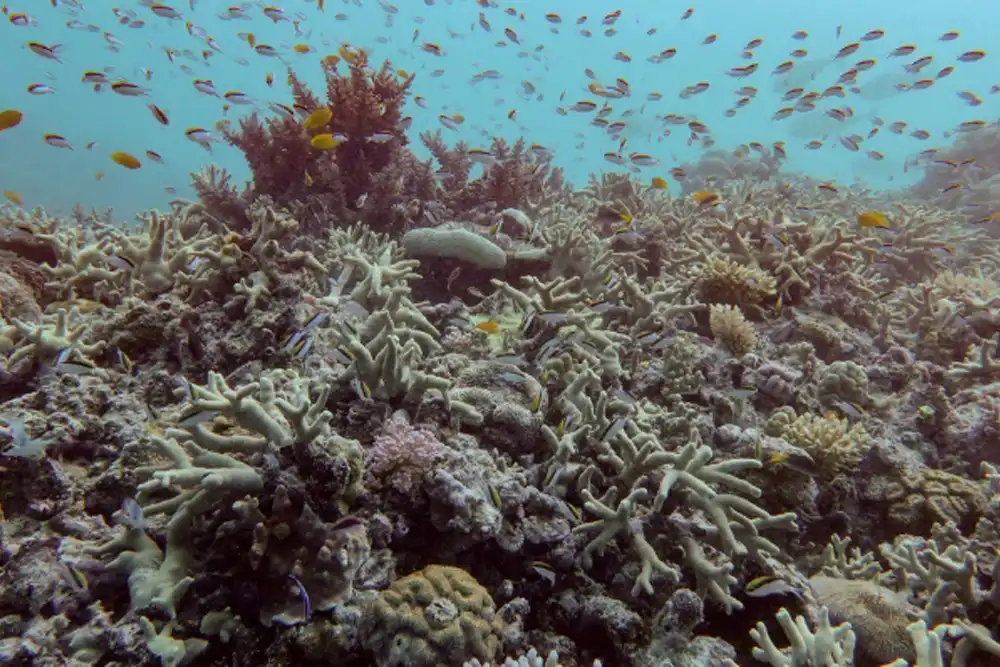

The main losses between 2024-2025 were of Acropora species – table corals and staghorn corals – which are both the fastest-growing species, largely responsible for the record increase in coral cover or recent years, but also the most susceptible to mortality as a result of bleaching.

Acropora are also more susceptible to damage from cyclones than their slower-growing relatives, and are a favourite prey of CoTS – outbreaks of which were detected on 27 of the surveyed reefs, with one in the Southern GBR classed as ‘severe’.

Overall, the AIMS scientists say that warmer-than-average water temperatures, which caused long periods of bleaching, were most responsible for the decline in coral cover.

Bleaching is the process by which warming water temperatures cause coral’s symbiotic zooxanthellae, a photosynthetic dinoflagellate (form of algae) which provides the coral with nutrients and colour, to be ejected by its host polyps.

Bleaching does not necessarily result in mortality. If the water temperatures return to normal, or the coral is able to acquire more heat-resistant zooxanthellae, the coral will survive and regain its colour.

The length of time that a coral can survive without its symbionts is dependent on the species. Deeper, larger colonies of coral species such as Porites may survive for several months, but shallow, rapidly growing Acropora will succumb in a matter of weeks.

The GBR’s 2024 bleaching event was its fifth in a decade, part of a fourth global mass bleaching event which began in 2023 and affected almost every reef on the planet.

Western Australian reefs, including Ninglaoo, were also affected by the past year’s bleaching.

‘This year, Western Australian reefs also experienced the worst heat stress on record. It’s the first time we’ve seen a single bleaching event affect almost all the coral reefs in Australia,’ said AIMS CEO, Professor Selina Stead.

‘Mass bleaching events are becoming more intense and are occurring with more frequency, as evidenced by the mass bleaching events of 2024 and 2025.

‘This was the second time in a decade that the Reef experienced mass bleaching in two consecutive years.’

‘These results provide strong evidence that ocean warming, caused by climate change, continues to drive substantial and rapid impacts to reef coral communities.’

For more from AIMS’ long-term reef monitoring project, and to download the complete 2024-25 report, head to www.aims.gov.au