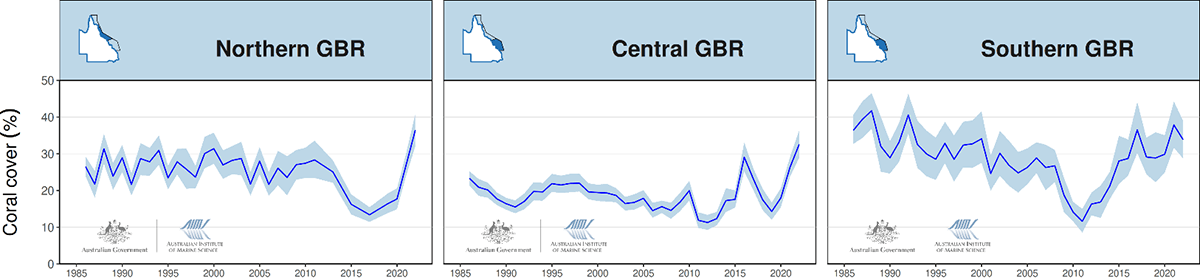

Coral coverage across the northern and central parts of Australia’s Great Barrier Reef has reached its greatest extent since monitoring began 36 years ago, according to the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS).

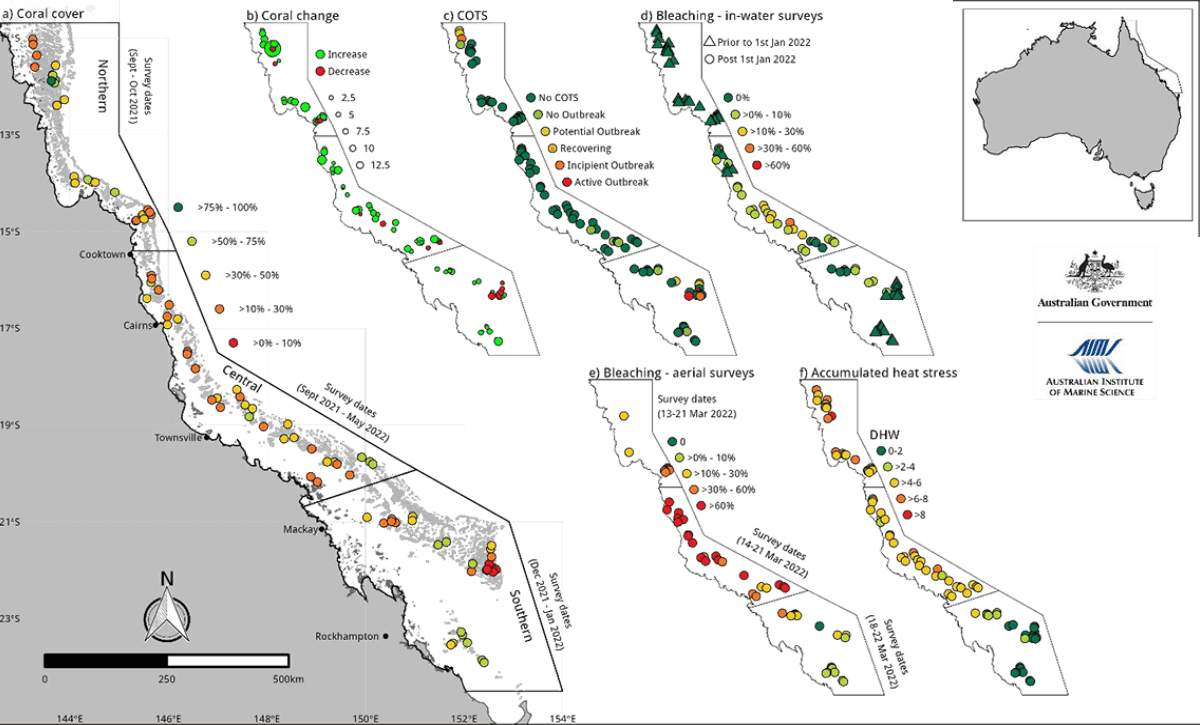

Coral cover in the southern part of the reef, however, has decreased slightly during the last year’s measurement, in large part due to a mass crown-of-thorns (COTs) starfish outbreak.

In a report published on 4 August, AIMS states that across the 87 representative reefs surveyed between August 2021 and May 2022 under the AIMS Long-Term Monitoring Program (LTMP), average hard coral cover in the region north of Cooktown increased to 36 per cent (from 27 per cent in 2021) and to 33 per cent in the central Great Barrier Reef (from 26 per cent in 2021).

In the southern extent of the reef, between Prosperine and Gladstone, cover had decreased from a high of 38 per cent in 2021 to 34 per cent by May 2022. AIMS reports that one-third of the gains made during the previous year had been lost to the COTs outbreak.

While the recovery is undoubtedly good news, AIMS remains cautious about the future as increasingly warmer waters create the potential for further mass bleaching events to occur. A mass bleaching event earlier in 2022 was the fourth recorded in just seven years, and the sixth since 1998.

AIMS CEO Dr Paul Hardisty said the increased frequency of mass coral bleaching events was ‘uncharted territory’ for the Reef, particularly as this year’s event occurred during a La Niña event, the cooling phase of the El Niño Southern Oscillation, when water temperatures are generally cooler.

‘In our 36 years of monitoring the condition of the Great Barrier Reef we have not seen bleaching events so close together,’ said Dr Hardisty. ‘Every summer the Reef is at risk of temperature stress, bleaching and potentially mortality and our understanding of how the ecosystem responds to that is still developing.

‘The 2020 and 2022 bleaching events, while extensive, didn’t reach the intensity of the 2016 and 2017 events and, as a result, we have seen less mortality,’ added Dr Hardisty. ‘These latest results demonstrate the Reef can still recover in periods free of intense disturbances.’

‘These corals are particularly vulnerable to wave damage, like that generated by strong winds and tropical cyclones,’ said Dr Emslie. ‘They are also highly susceptible to coral bleaching, when water temperatures reach elevated levels, and are the preferred prey for crown-of-thorns starfish. This means that large increases in hard coral cover can quickly be negated by disturbances on reefs where Acropora corals predominate.’

AIMS monitoring program team leader Dr Mike Emslie said the 2022 results built on the increases in coral cover reported for 2021, with most of the increase continuing to be driven by fast-growing Acropora corals. The expansion of the cover and recovery of the reef has in part been aided by a relatively quiet period free of intense storms.

Dr Emslie said climate change was driving increasingly frequent and longer-lasting marine heatwaves, which may prevent bleached coral from recovering sufficiently before the next bleaching event occurs.

‘The peak of the most recent bleaching event in March occurred when the accumulated heat stress caused widespread bleaching but not extensive mortality,’ said Dr Emslie. ‘The increasing frequency of warming ocean temperatures and the extent of mass bleaching events highlights the critical threat climate change poses to all reefs, particularly while crown-of-thorns starfish outbreaks and tropical cyclones are also occurring. Future disturbance can reverse the observed recovery in a short amount of time.’

The annual summary report is available for download from the AIMS website. A short summary report is available here.