A new study has been published detailing the successful blood-sampling and ultrasound scanning of wild, free-swimming Galápagos whale sharks in order to observe their reproductive status, the first time such techniques have been applied in the wild.

The paper, ‘Underwater ultrasonography and blood sampling provide the first observations of reproductive biology in free-swimming whale sharks’ is the collective effort of a global team of scientists from the Okinawa Churashima Foundation, Atlanta’s Georgia Aquarium, the Galápagos Whale Shark Project, Galápagos National Park and Marine Megafauna Foundation

It is hoped that the new techniques will help scientists further understand the physiology of wild, endangered marine species.

Although whale sharks are a relatively well-studied species of shark, little is known about their reproductive habits. Most of the animals commonly encountered at coastal reefs by scuba divers are juvenile males, whereas the females remain further offshore, making them difficult to find, and therefore study.

Furthermore, while the South Atlantic Island of St Helena is thought to be a meeting point where adult male and female whale sharks gather in equal numbers to choose a partner, mating behaviour has only rarely been witnessed and, to date, there are no known birthing areas or nurseries for the species.

Only one pregnant female has ever been examined by scientists, caught by a Taiwanese fishery in 1995 and found to be carrying 304 eggs and whale shark pups – some still inside their egg-cases; others free-swimming with the mother’s uterus.

More great reads about whale sharks

- 10 of the best places to dive with whale sharks

- International shipping threat to endangered whale sharks

- Study shows need for whale shark population monitoring

- St Helena’s whale shark mating secret

- How and why is the whale shark the world’s largest fish

The study was conducted during 2017 and 2018 around Darwin Island in the Galápagos Marine Reserve, one of the only places in the world where adult female whale sharks are consistently seen, often with distended abdomens, thought to be indicative of pregnancy.

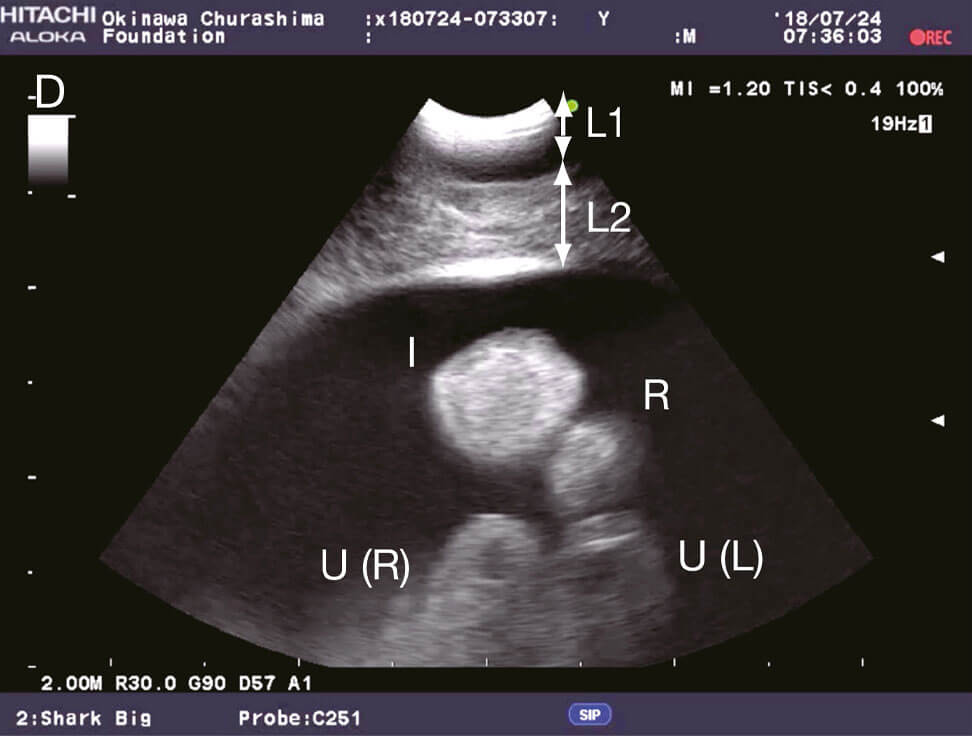

Lead researcher, Dr Rui Matsumoto, of the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium in Japan, took the ultrasound samples using a portable ultrasound diagnostic imaging system, approximately 17kg in weight, while wearing a tank-mounted thruster to keep pace with the whale sharks.

‘These techniques were quite challenging to apply,’ said Simon Pierce, co-founder of Marine Megafauna Foundation. ‘First, we’re working at 10–30 m beneath the surface, often in strong currents. Second, whale sharks are wonderfully placid, but they’re a lot faster than us, and emerge from the blue with little warning; we only get a short time to work with each animal.

‘The ultrasound unit is the size of a large briefcase, so it’s far from hydrodynamic,’ added Pierce.

Blood samples were taken by the scientists while swimming alongside the sharks, a particularly challenging task involving two syringes connected by a three-way stopcock, an extension tube and two large needles, in order to avoid seawater contamination of the samples.

‘Collecting blood samples from free-swimming sharks is… something that has taken a lot of trial and error to get right,’ said Pierce. ‘Whale sharks have extremely thick skin, so we can’t reach their actual veins – instead, we’re trying to draw blood from vascularised tissue on their fins. That generally only works on relaxed sharks, and requires a large dose of luck!

‘We also have to avoid contamination from seawater, which has necessitated the development of a two-syringe system, with one creating an initial vacuum, enabling the second to draw pure blood.’

Of the 22 whale sharks that were scanned, none were found to be pregnant, further deepening the mystery of whale shark pregnancy as the distended abdominal region was found to be nothing more than layers of skin and muscle. The scientists postulate that this anatomical feature ‘may simply be a secondary sex characteristic of whale sharks, and not an indicator of pregnancy.’

Although the research has provided no new insight into the reproductive behaviour of whale sharks, the technology developed as a result is nevertheless a huge step forward in safe, non-invasive techniques for the study of marine megafauna.

‘Shark biology studies used to be based on dissection,’ said Dr Pierce. ‘For endangered species like the whale shark, where we’re doing everything possible to keep them alive, that’s made us quite creative in the development and application of new techniques, such as underwater ultrasound and in-water blood sampling.

‘Now, we can start investigating their reproduction while they’re in the wild – and it’ll allow for other studies too, such as looking at stress or pollution levels in their populations, which really improves our understanding of their conservation needs.’

Following the study’s publication, the scientists also hope that the techniques will be extended to other species.

‘Whale sharks are gentle giants, so they’re lovely animals to work with, and have become a bit of a poster species for the use of new techniques, like photo-identification and laser photogrammetry, that are then adapted for other endangered sharks and rays,’ said Pierce.

‘Other groups are already starting to use underwater ultrasound wands on poles to scan tiger sharks while they swim by. It’s going to unlock a lot of new opportunities for minimally-invasive research, that can give us a wealth of information while avoiding any harm to the animals,’ he added.

‘It’s been a super exciting project to be part of!’

‘Underwater ultrasonography and blood sampling provide the first observations of reproductive biology in free-swimming whale sharks’ by Rui Matusmoto et al, is published under an Open Access license in the online journal Endangered Species Research.

- New shark-repellent hook could cut longline bycatch by more than 60 per cent - 17 February 2026

- Perth dive operator fined after leaving divers behind - 16 February 2026

- Aggressor Adventures announces upgraded Red Sea Aggressor IV - 13 February 2026