Mark ‘Crowley’ Russell asks co-author of Whale Sharks, and co-founder of the Marine Megafauna Foundation, Dr Simon Pierce, what we still need to find out about this elusive species

DIVE: What first inspired you to study whale sharks?

SIMON PIERCE: Whale sharks are awesome. They grow from 50cm at birth to become the largest fish that has ever lived. They dive to at least 1,900m. They swim more than 10,000km a year, often without approaching a coast. And they manage all this with a big goofy grin and a general ‘oceanic Labrador’ vibe. These spotted giants really are quite endearing. I fell in love with whale sharks the first time I got to work with them, back in 2005. At that stage, little was known about their lives and habits. We’ve learned a lot more in the years since (cue sound of our new 340-page book thumping on the table), but many interesting mysteries still remain…

DIVE: Why do divers mostly encounter juvenile males?

SIMON Whale sharks were only discovered by Western scientists in 1828. Until the 1980s, there had only been a few hundred reported encounters with the species. Even Jacques Cousteau only ever saw two. We know now that the key is to find places where there are high densities of their preferred prey, zooplankton and small fishes. Whale sharks have permanent munchies. In some areas, such as off the Yucatán coast of Mexico, several hundred sharks can be seen feeding at once, gathering in a sharky constellation to exploit mass tuna-spawning behaviour.

That’s interesting in itself, but not particularly mysterious. The odd thing is that it’s almost exclusively male whale sharks that frequent these areas. Most of the sites associated with whale-shark tourism – think Ningaloo Reef in Australia, South Ari in the Maldives, multiple areas in the Philippines, Mafia Island in Tanzania, and others – are dominated by juvenile males. The occasional juvenile female is certainly present, but it’s rare to see adult females at any of these locations.

‘Sexual segregation’, as this situation is referred to, is common in sharks and rays. Normally, though, the ‘segregated’ part of the population hasn’t been hard to find. In whale sharks, for the most part, we still don’t know where the females live. They seem to be using completely different areas

Why aren’t female whale sharks taking advantage of these predictable buffets? Well, adult and subadult male sharks will both harass juvenile females (also each other, boats, even whale shark researchers), so that’s one good reason for the females to avoid them, but this segregation persists even in places where no large males are present. Perhaps productive feeding areas attract more whale shark predators? For males, the main aim is just to eat lots and grow fast to reproductive size, so rich but risky habitats might be worth it. Females benefit (in evolutionary terms) by playing the long game, growing more slowly to a larger size, so they could prefer to live in safer areas elsewhere. Smart.

I think it’s most likely that females are feeding on slightly different prey, and presumably offshore; otherwise, we’d be seeing them more often. The best way to answer this conundrum will likely be through long-term tracking studies that allow us to directly compare and contrast habitat preferences between the sexes. We can also use biochemical techniques to look at long-term diet and habitat use across populations. Early work using these methods hasn’t seen many clear differences emerge between the sexes yet, but… most of our data is from males, because we know where they are. Sigh.

DIVE: Are there any places you regularly see females?

SIMON: The northern Galápagos Islands is one area where adult female sharks are regularly seen, and it’s one of my favourite places to work. Most of the sharks we see there are 10–12m in length, and almost all are females. It’s not a feeding area, and they don’t stick around – most sharks are only there for a day or so, at most. When I first saw these sharks, apart from being gobsmacked by their sheer size, I was flabbergasted by the ‘junk in their trunk’. These sharks had a massive ‘bump’. Clearly pregnant, we assumed.

In 2018, we were able to recruit the Okinawa Churaumi Aquarium research team to join us for an expedition. These Japanese scientists are the world leaders in using waterproofed ultrasound units for reproductive assessments. They collected ultrasounds from multiple sharks, and… nothing. Whale sharks have extremely thick skin, so it’s difficult to be definitive about it, but it seems likely now that females close to adulthood develop a pronounced ‘bump’ – though it doesn’t necessarily mean they’re carrying pups. Confusing, but that’s science.

For the moment, anyway, we’re back to having only one confirmed pregnant whale shark to talk about. That 10.6m ‘megamamma’, caught off Taiwan in 1995, contained around 300 cute little pups. It’s very rare to see adult female whale sharks close to the coast, so we assume they’re living in the open ocean. That makes them hard to study. Hopefully, we can find another ‘megamamma’ sometime soon.

DIVE: Where are the pups?

SIMON: If bus-sized pregnant sharks have proved challenging for us to find, imagine trying to find a baby one. Only 30 to 40 newborn whale shark pups have ever been found, scattered across the world. Pups are born free-swimming, and it is likely that they get no further assistance from their mother. My working hypothesis (or arm-waving speculation) is that we don’t see them because the mothers are giving birth well offshore, away from coastal predators, and the babies are following the daily vertical migration of plankton from the depths to the surface when darkness falls. I could be embarrassingly wrong though. It wouldn’t be the first time.

DIVE: How old do whale sharks get?

SIMON: Whale sharks become adults at about 7–9m length in males, and about 9–10m in females. Age-wise, our best guess is that those sizes correspond with about 25 years for males, and 30 to 40 years in female whale sharks. We know that the largest whale sharks ever recorded have been in the 18 to 20m range. Working out their maximum lifespan should therefore be a simple exercise in extrapolation, right?

If only it were that easy. Shark skeletons are made of cartilage, not bone. The ‘centra’ in their vertebral column continually grows as cartilage accretes through time. Like a tree, the centra forms a dark band during times of slow growth, and a lighter band when the shark grows faster. Each band pair can represent a year, as with trees. Unfortunately, whale sharks – and you can trust me on this, I’m a doctor – are not trees. Whale sharks feel no obligation to suffer through winter. If it gets cold, they just go somewhere else. That means the band formation may not be annual.

Once they get to around their adult size, whale shark growth slows down dramatically. The relationship between the shark’s size and age breaks down completely. Two whale sharks, Stumpy and Zorro, have been returning to Ningaloo Reef in Australia for more than 20 years. The research paper describing their sighting histories notes that ‘their growth has been negligible over the past two decades’. They may still form bands in the centra, but there’s a good chance they’ll be indivisible, even under a microscope.

So how old do whale sharks get? We don’t know. Most large shark species are long-lived and slow-growing. Greenland sharks, living in the cool, deep Arctic waters, grow less than 1cm per year and can be more than 6m long at full size. A 5m female was estimated to be 392 years old. Female white sharks only become adults at about 33 years, and are estimated to live to at least 73. Even small, spiny dogfish are thought to live for at least 80 years. There’s a good chance that the whale shark’s maximum lifespan will easily exceed our own.

DIVE: Some of the data from tagging research reveals whale sharks dive to great depths. Why?

SIMON Whale sharks are incredible deep-divers – probably to deeper than 2,000m (whereupon the pressure crushes our tags). The open ocean may be boring at the surface, but there’s plenty going on in the mesopelagic depths just a few hundred metres beneath. Literally trillions of lanternfishes, probably the most abundant vertebrate on the planet, live in this twilight zone. They’d make an excellent snack for a hungry whale shark. But why do they keep going deeper?

There are lots of good reasons not to go deeper. There isn’t much food in the deep ocean, it’s lower in oxygen, and it’s very cold, with whale sharks occasionally facing near-freezing 2ºC temperatures. They aren’t just diving for the fun of it, as they have to spend time warming up at the surface afterwards. We’re not sure what the purpose of these deep dives is yet, but an intriguing possibility is that it’s a part of the shark’s geomagnetic navigation strategy – they are likely to get a better fix on the Earth’s magnetic field closer to the crust, much as we might go outside to get a better GPS signal. At the moment, whale sharks are showing us the limits of our technology, depressingly (and expensively) quickly, so the reasons behind these behaviours remain unknown.

DIVE: What’s the future looking like for whale sharks?

SIMON Whale sharks are a really special species. They’re gigantic. They’re iconic. They’re also globally endangered. Their large size, placid nature, and the existential threats to their very survival keep motivating us to develop new and improved research techniques to learn more about them.

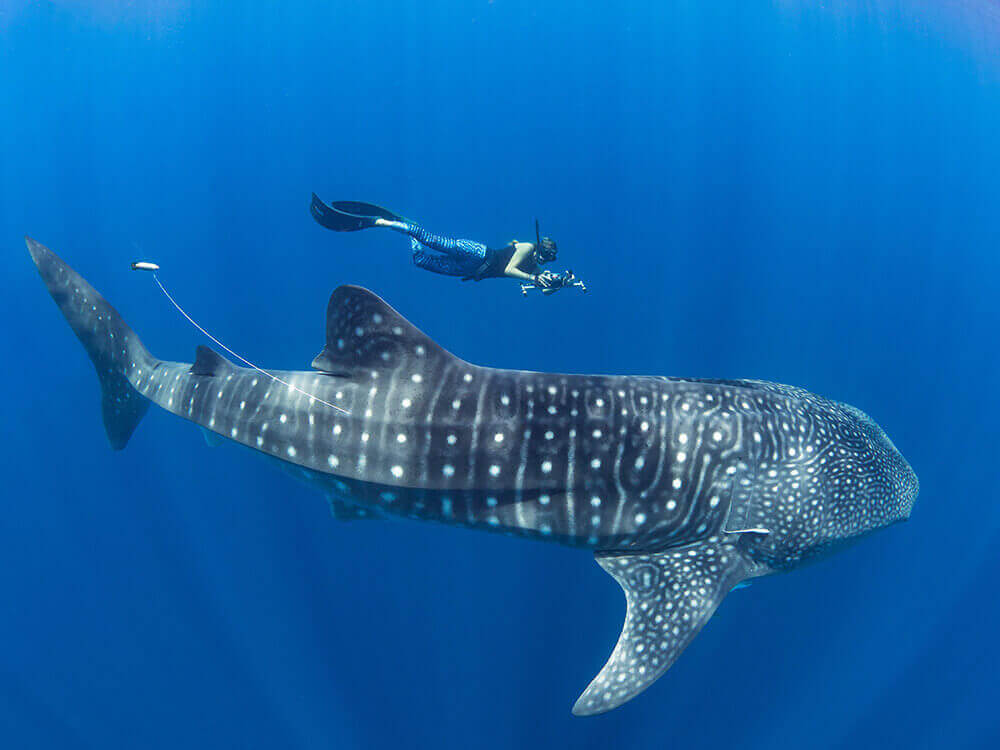

Many of the non-invasive study techniques that were first pioneered on whale sharks, such as photo-identification, are now standard methods in research with other shark and ray species, and we’re pushing forward to integrate artificial intelligence with image processing so we can work faster at identifying individuals. Some of the first satellite-linked tags were designed for and deployed on whale sharks to track their movements across vast distances. Whale shark scientists are continuing to trial new techniques, such as ultrasound on free-swimming sharks, underwater blood draws, even in-water semen collection.

We’ll keep solving mysteries, but that certainly will not diminish the wonder and joy of encountering these colossal sharks. The very existence of whale sharks makes the world bigger for all of us.

Edited by Alistair D M Dove and

Simon J Pierce, CRC Press, £72

ISBN 978-1-138-57129-7