Mark ‘Crowley’ Russell warns that all too often, divers are unaware of the impact of nitrogen narcosis until it is too late

Back in my days as a full-time instructor, I was conducting the 40m dive of a Deep Diver speciality course when one of my students started indicating that there was a problem with his computer – a virtually identical model to my own – and the display of his computer read precisely the same as mine.

He kept waggling his hand in the ‘I have a problem’ sign and pointing ever more vigorously at his computer. I kept checking and everything was perfectly fine, but the student diver was becoming increasingly agitated, so I decided to begin our ascent, using the standard practice of facing the panicky diver, making eye contact, giving plenty of ‘Okay’ signs and reassurance.

At around 25m his eyes widened, as if a 10,000-lumen metaphorical lightbulb had suddenly lit up above his head, and he looked up to the surface, cleared his fully-flooded mask, checked his computer again and gave me a big, very relieved, ‘Okay’ sign. There had never been a problem with his computer; he just couldn’t see the display through his flooded mask, and he hadn’t noticed – a classic, and slightly comical case of nitrogen narcosis.

Except, upon reflection later that day, it wasn’t comical. It wasn’t funny at all. We might laugh at a guy who was so narc’d he didn’t realise his mask was flooded, but then – neither did I. The guy in charge – the chap responsible for these people’s lives – hadn’t noticed that his student’s mask was flooded, while staring him in the face.

It was – no pun intended – a sobering realisation, and one I used often during the rest of my professional career, because I learned one of the most important lessons about nitrogen narcosis that day: you can dive at depth and never realise that you are suffering the effects of breathing air under pressure, until it’s all gone wrong, and it’s all too late.

There were other examples. The time that a divemaster candidate supervising a Wreck Diver speciality led his divers in completely the wrong direction, almost getting them pushed out to sea by the current in the process*; the time I was on a 40m dive in poor vis when all the particulate matter drifting past the periphery of my vision made me feel as if I was about to make a sci-fi leap into hyperspace; or the time when my dive buddy went absolutely crazy and swam off like a ballistic missile into the cargo hold of a shipwreck that – fortunately – was very open and very easy to dive.

My point is, that narcosis is often talked about as if it were some sort of comedy routine. I remember a picture in an old training manual which had a cartoon of a diver with a pink elephant in the background, offering his regulator to a fish. I think this highlighted much that is wrong with the way narcosis is often thought of – that it’s a bit like people doing daft things under the influence of alcohol, or indulging in certain recreational pharmaceuticals as enjoyed by The Beatles, circa 1966.

Yes, there are moments that are funny in hindsight, but what if my student with the ‘broken’ computer had panicked and bolted from 40m? What would have happened if I had bolted after him? What if that trainee divemaster and his students had been pushed off the wreck that day? What if my buddy had torpedoed herself into one of the holds of a deeper, more enclosed shipwreck?

*yes, also me!

THE HISTORY OF NITROGEN NARCOSIS

In 1821, Swiss botanist and physician Louis Théodore Colladon described feeling a ‘state of excitement as if I had drunk some alcoholic liquor’ during a 20-metre descent in a diving bell. It seems odd, given the shallow depth – it is entirely possible he was just happy to be there – however, it is the first reported case of what we would identify today as sub-aquatic narcosis.

The symptoms were formally described in 1834 by Swiss-French Physician Victor T Junod, who wrote in a paper discussing the therapeutic effects of ‘air compression and rarefaction’, that ‘in affected persons, the functions of the brain are activated, imagination is lively, thoughts have a peculiar charm and, in some persons, symptoms of intoxication are present’.

In 1859, American professional diver, John B Green, wrote in his brilliant book Diving, With And Without Armor, that he noticed a feeling of ‘excitement followed by drowsiness’, at a depth of 150ft (46m), at which point he felt it was time to end the dive; the effects were also reported by the British Admiralty in 1930 following extensive deep-diving trials conducted by the Royal Navy, during which divers were reported as sometimes suffering from ‘giddyness’ and memory loss. One diver wrote in his debrief that ‘suddenly, something seemed to … snap inside my head, and I started to … go mad at things.’

The Admiralty appears to have initially dismissed the symptoms as some form of mental instability – indeed, a 1932 report entitled ‘Recent Research Work in Deep Sea Diving’ recounts how one poor sailor became so distressed at depth that ‘to keep his mind temporarily off the subject’, he was ‘sent on shore with two of his fellow divers and plied to the brim with alcohol.’

In 1935, US Navy physician, Albert R Behnke – who also separated the phenomenon of arterial gas embolism from decompression sickness – theorised that it was nitrogen breathed under pressure that caused narcosis. His theory was confirmed in 1939, when US Navy divers were called to rescue the crew of the submarine USS Squalus, which sank during testing off the coast of Portsmouth, New Hampshire, to a depth of 74m. The Navy divers were using an experimental mixture of helium and oxygen to prevent the effects of decompression sickness, already known to be caused by nitrogen, but found that they did not experience the ‘cognitive impairment’ usually present during deep dives.

The root cause of how nitrogen and other inert gases – including argon, xenon and krypton – induce narcosis remains uncertain. In 1899 and 1901, German pharmacologist Hans Horst Meyer and British/Swedish physiologist Charles Ernest Overton theorised that it was caused by pressurised gas dissolving into the lipids (fats) that surround an animal’s brain cells.

The Meyer-Overton hypothesis, as it is known, formed the basis of inert gas anaesthesiology until the 1980s, when it was challenged by British scientists Nick (now Professor) Franks and William Lieb, who suggested the effect is caused by gases interacting with the proteins that are also present in animal cell membranes.

The short version is: gas under pressure dissolves into our brain cells and makes us feel a bit squiffy, although we’re not exactly sure how.

WHY NITROGEN NARCOSIS MATTERS

The comparison of nitrogen narcosis with alcohol consumption is apt, in that the effects can build so slowly they are barely noticeable – until, that is, somebody in the pub asks you a question and you are unable to immediately remember the answer. We can fall about laughing while we’re all standing at the bar, but it’s a very different story for the car driver who says they ‘feel fine’ after a pint, but is unable to immediately effect an emergency stop when a child runs into the road.

The effects of nitrogen narcosis are not usually noticed until a diver hits around 30m, and become exaggerated at greater depths, but the lack of immediately obvious sensation at slightly shallower depths does not mean that recreational divers should not be wary of it happening, even though many claim – wrongly, in my opinion – to have ‘never been narc’d’.

Small issues can become big problems very quickly underwater. Forgetting to dump air from your BCD – or pulling the wrong cord – could quickly instigate a rapid ascent for an inexperienced diver. Failure to monitor computers and gauges can lead to low or out-of-air incidents, or even straying into the depths when there is no sea floor: a colleague of mine once had to swim two inexperienced divers up from 55m, who were otherwise tootling along admiring the reef, blissfully unaware of the danger they were sinking into.

Exact figures are difficult to come by, but historical incident reports compiled by the British Sub-Aqua Club (BSAC), DAN and the Australian Diving Incident Monitoring Study suggest that narcosis was a factor in between two and nine per cent of reported diving incidents. Although most of these incidents were not fatal, some of them were; and most of those, perhaps, didn’t need to happen.

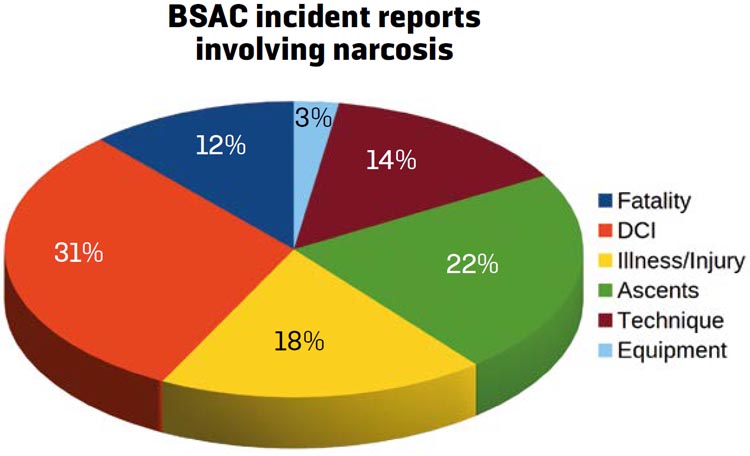

The chart above shows the 121 diving incidents reported to BSAC between 1965 and 2022 in which nitrogen narcosis was specifically named as a contributory factor. The number seems small but those are only the incidents that are reported, and – rather in the way it’s often not possible to tell if a person is stone-cold sober or has just polished off a large glass of wine – it’s not easy to tell if somebody’s narc’d.

The 14 reported fatalities in which narcosis may have been a factor represent around two per cent of the total number logged by BSAC during the same time period. The number, again, seems small – although no diving fatality is insignificant – but most people won’t need to be reminded that, while the club’s incident reporting database provides an invaluable contribution to global diving safety, the data is collected from a relatively small pool of divers. With an estimated nine million active divers in the world right now, that is, potentially, a lot of incidents.

PREVENTING NITROGEN NARCOSIS

Mitigation for narcosis comes in the form of helium, which deep technical divers use to reduce the amount of nitrogen in their tanks (trimix) or remove it completely (heliox), but this is not a practical option for recreational diving. It is worth pointing out that some recreational divers cling to the belief that enriched air nitrox can help reduce the effects, however, oxygen is almost as narcotic under pressure as nitrogen, so it makes little difference.

Unlike alcohol, of course, the effects of nitrogen narcosis wear off almost immediately upon ascent. The easiest preventative measure for recreational divers, therefore, is not to make deep dives, but I don’t believe they should be avoided entirely. Most recreational divers will make a 30m dive to earn their Advanced Open Water certifications, but I would also encourage divers to take the extra 40m deep dive and pay attention to the effects as they occur. Experience and understanding of narcosis is an important part of a diver’s education, especially as a novice.

Take supervised courses, build up some experience, learn your tolerance and, when you do make deeper dives, remember that you should think a little more carefully about your actions, and don’t make the mistake of believing you’ve ‘never been narc’d’ just because you didn’t see the pink elephant.

It was Jacques-Yves Cousteau who, in 1953, described the effects of nitrogen narcosis as ‘l’ivresse des grandes profondeurs’ or ‘the raptures of the deep’. Personally, I think the most rapturous recreational diving is when you are no deeper than 20m or less, where you get the best of the light, the most beautiful coral, less likelihood of narcosis – and much, much longer dives.

- DIVE’s Big Shot Light and Shadow – win an Aggressor Adventures liveaboard trip - 12 February 2026

- Dylan Harrison instructor charged over her death - 9 February 2026

- The waters of Wakatobi are an artists’ muse - 6 February 2026

More great reads from our magazine

- Fiji’s Pacific shark feeding boom

- The Red Army – Cornwall’s kingdom of spider crabs

- The ride of your life! Scootering with Maldives grey reef sharks

- Scuba diving the Florida Keys – America’s coral archipelago

- Battle of the Colours – the mating ritual of giant cuttlefish