The High Seas Alliance names eight biodiversity hotspots that could become the first marine protected areas in international waters under the new UN High Seas Treaty.

After two decades of negotiations, the UN’s High Seas Treaty, the first-ever global agreement to protect the open ocean from ecological devastation, was signed into effect on 20 September.

Sixty-six countries signed the UN’s Treaty on Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) on its first day of signatures.

The treaty will allow member states to establish marine protected areas (MPAs) in international waters to shield key habitats from the destructive effects of unsustainable exploitation and overfishing.

Despite covering over half of the earth’s surface and providing a home for some of the most unique and most biodiverse habitats on the planet, only one per cent of the high seas are currently under legal protection.

Rebecca Hubbard is the director of the High Seas Alliance (HSA), a group of more than 50 NGOs that have led the efforts for the BBNJ treaty for the last decade. She told DIVE: ‘For many years, we have not had the laws and protections that we need to properly protect life in the high seas, which means that this really important environment has been exposed to extreme pressure.’

This could soon be set to change. Once 60 countries have ratified the treaty by writing it into their national law, the agreement will take effect after 120 days.

You may also like:

But the international community will need to move quickly if it wants to make good on the UN’s ‘30 by 30’ pledge – protecting 30 per cent of the ocean by 2030.

The HSA has put forward eight ‘priority protection’ suggestions for the first wave of MPAs.

‘We chose areas based on their unique biodiversity values,’ Hubbard explained. ‘They’re representative of the kinds of sites we need to be acting really quickly to protect.’

These are the eight unique areas the HSA have spotlighted:

1. South Tasman Sea / Lord Howe Rise

The High Seas Alliance described Lord Howe Rise in the South Tasman Sea as ‘a volcanic lost world’. A mile below the surface in the waters between Australia and New Zealand, the Lord Howe Rise is a submerged vista where a vast plateau and “abyssal plains” are overlooked by an underwater mountain chain.

The Lord Howe Rise touches the surface at two points, forming the three most southerly coral reefs on earth: the Middleton and Elizabeth Reefs and Lord Howe Island.

Elizabeth Reef is considered one of the most pristine and unexplored sites of the Great Barrier Reef.

Diver and marine biologist Johnny Gaskell described the reef as ‘truly one of the most incredible coral habitats I have ever seen.

‘This site has considerably high coral cover, particularly on the reef edge. Up to 100 per cent in some parts, which is outstanding and makes it one of my favourite dive sites.’

At least 348 demersal fish species, cold-water corals, petrels and the Antipodean wandering albatross all rely on the unique habitat in the South Tasman Sea. It’s also an important thoroughfare between breeding and feeding areas for humpback and southern right whales.

Unfortunately, many of the vulnerable ecosystems that flourish here are ‘fishable depths’, according to South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management. Frequently targeted by fisheries for orange roughy, bottom trawl gear devastates the slow-growing corals and sponges that are often keystone species.

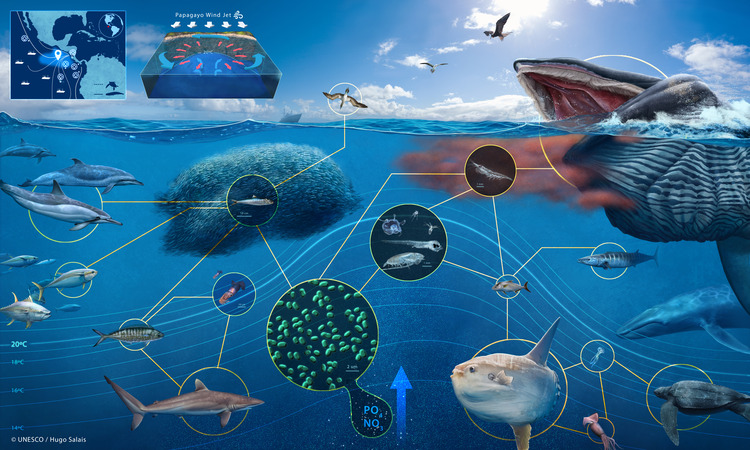

2. Costa Rica Thermal Dome

Hubbard names the Costa Rica Thermal Dome more of ‘a phenomenal ecological wonder’ than a fixed location. Every year in the Eastern Pacific, a collision of swirling seasonal winds and ocean currents draws cold, nutrient-rich water from the depths of the ocean to its surface in a dome-shaped swelling.

Blue-green algae flourish in this nutrient feast, which attracts trillions of zooplankton and krill, kickstarting ‘one of the richest marine food webs known to science’, according to HSA. It also acts as a significant carbon trap and could be critical in the fight against climate change.

The phenomenon moves from year to year and varies in size from 300 to 15000 kilometres, which makes it hard to protect. However, wherever it appears, it supports an estimated 1,400 blue whales and provides a migration corridor for dolphins, sharks, rays, marlins and sea turtles.

But these creatures often fall victim to the virulent overfishing in the region. Shipping traffic on its way to the Panama Canal, ship strikes and plastic pollution are all threats too.

3. Emperor Seamounts

Extending across 2000 kilometres of seafloor between Hawaii and the Kamchatka Trench at the border of Russia is a chain of 80 mostly underwater mountains that make up the Emperor Seamounts.

The range hits the surface at Hawaii’s north-western islands and was formed by the same chain of volcanic eruptions. A frequent lure for scientific divers, these spots nearer the surface play host to thousands of rare coral, sponge and algal growths and the colourful marine ecosystems they support. The islands are also home to the oldest known wild bird, a 71-year-old albatross called Wisdom.

In the depths of the North Pacific, ancient coral reefs – estimated to be 4,200 years old – form an ‘artery of biodiversity cutting across the often featureless deep sea’, according to HSA.

The High Seas Alliance suggests permanently closing the region to fishing once the treaty has been ratified. Already 19-29 per cent of research images of the Emperor Seamounts show trawling scars and abandoned fishing gear.

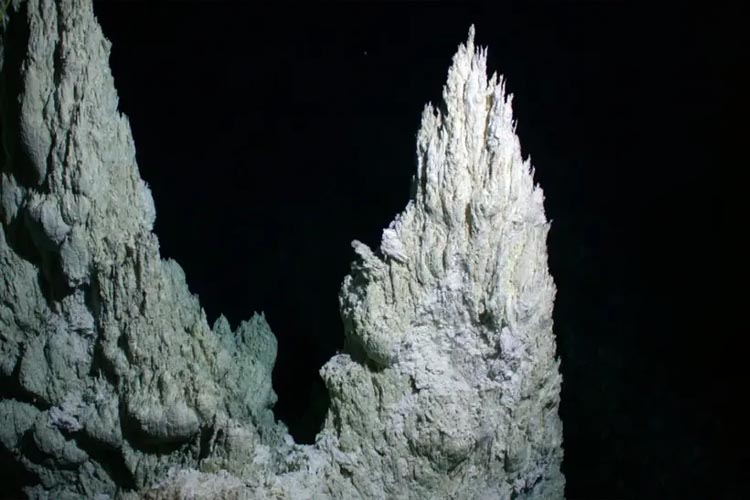

4. The Lost City Hydrothermal Fields

In 2000, US Navy researchers stumbled upon the Lost City on the slopes of the Atlantis Massif using a deep-ocean submersible. Footage showed a bizarre skyline of 30 250,000-year-old geothermal chimneys, ranging from one to 100 metres in height.

The extreme conditions of the 500-metre hydrothermal area, which regularly spews hot and highly alkaline water out of vents in the seabed, have not stopped a robust and biodiverse ecosystem from thriving there. Some scientists believe the chemical processes and the trillions of bacteria and microorganisms surviving in the Lost City might even hold the key to understanding the origins of life on Earth.

The geothermal field was proposed as a UNESCO World Heritage site of ‘outstanding universal value’ and was listed as a Mission Blue Hope Spot – places that are critical to the health of the Ocean – by the Marine Conservation Institute.

But in 2018, the International Seabed Authority approved a licence for Poland to explore 10,000 square kilometres of vents along the Atlantis ridge in search of cobalt, manganese, gold and other heavy metals. The search area does not extend to the Lost City, but far-reaching sediment plumes could choke local populations.

The exploration is in its early stages, and introducing an MPA for this underwater cityscape could put a halt to impending damage.

5. Sargasso Sea

Floating islands of interwoven Sargassum seaweed characterise this 3,200-kilometre-long and 1,100-kilometre-wide stretch of ocean. The only sea with no land borders, it is a huge carbon sequestration site and oxygen source, and home to a complex and highly specialised set of ecosystems.

Endangered species like the green, hawksbill, loggerhead and Kemp’s ridley turtle all use the area as a nursery for hatchlings, porbeagle sharks pup there and every American and European eel starts and ends life in the Sargasso Sea.

But the area is also home to one of the five notorious ocean garbage patches. The huge amalgamation of plastic waste blown into the remote sea by ocean currents poses an existential threat to the wildlife along with commercial fishing.

“It’s imperative that the Sargasso Sea receives urgent protection on a wide scale, for economic reasons as much as ecological ones,” the HSA commented. The deterioration of the site, which also supports the whale-watching industries of the Caribbean, has a significant knock-on effect on global marine life.

6. Walvis Ridge

This 3,000-kilometre chain of seamounts between the Namibian coast and Tristan da Cunha in the mid-Atlantic remains largely a mystery.

At 4,000 metres depth, scientists assume the complex topography supports a highly biodiverse community of marine mammals, species of tuna and coral.

In 2007, SEAFO, the regional fisheries management, decided to go against the advice of its own scientists, who suggested a ban on trawling and gill netting to protect the wildlife here. Plans for offshore oil and gas drilling in Namibian waters are also raising concerns for the area’s future health.

‘Seamounts are always biodiversity hotspots,’ said Jonny Hughes from the Blue Marine Foundation, who have started scoping the site to determine how best to protect it once an MPA has been established. ‘The range of depth in Walvis Ridge means there’s also a huge diversity in habitats and endemic species.’

Tristan da Cunha is a part of the British overseas territory of St Helena. The 250 residents voted in 2020 to create a marine protected zone or ‘blue belt’ to help the island’s marine life recover.

The HSA hope that the presence of this blue belt will encourage further protection of the region.

7. Salas y Goméz & Nazca ridges

These ridges are counted as some of the most ecologically significant areas in the world. Overflowing with rare wildlife, nearly half of the creatures living here cannot be found anywhere else on Earth.

On top of boasting some of the clearest waters in the world, the 110 volcanic peaks that make up the Salas y Goméz & Nazca ridges provide habitats and thoroughfares for 82 at-risk species, including 25 types of shark.

So far, the 2,900-kilometre range has mostly escaped aggressive fishing activities. But climate change is starting to cause ocean acidification, a process which eats away at minerals crucial for corals and crustaceans and encourages harmful algal blooms.

Chile and Peru have already introduced protections for the parts of the ridge in their waters, but 73 per cent of it is in international waters and would need to be protected under the new MPAs.

8. Saya de Malha Bank

This scuba hotspot is known for its colourful array of tropical fish, sea mammals and unusual underwater landscape. The Saya de Malha bank in the Indian Ocean consists of a shallow ridge connecting Seychelles and Réunion.

The marine area is unique for nurturing the largest seagrass meadow in the world. This gently swaying seascape is not only a crucial habitat, home to the dugong and the tiger shark, but it also hoovers up carbon 35 times faster than tropical rainforests. Though seagrass meadows cover less than 0.2 per cent of the world’s oceans, they take up almost 10 per cent of its carbon every year, according to a report by the World Resources Institute.

Greenpeace has sent a number of expeditions to Saya de Malha. They created this map of sightings of whales, dolphins, turtles and rare fish to emphasise the ridge’s importance. They said: ‘We urgently need a vast network of ocean sanctuaries, free from destructive human activity, where sharks and other marine life can recover’.

The MPAs will not come into effect automatically once the treaty is ratified. ‘The symbolic signing of the treaty is an important step – but we have to be very careful,’ Jonny Hughes from Blue Marine Foundation said. ‘Once the treaty is ratified, that’s when the hard work starts. We need to make sure governments aren’t making grandiose statements about marine protection – but not following through with their actions.’