Far beneath the waves, a race is unfolding to claim ownership of the world’s seabed and the minerals it contains. But is the rush to deep-sea mining putting global marine biodiversity at risk?

By Chris Fitch

Deep undersea mining is taking off. ‘In 2001, there were just six deep-sea mineral exploration contracts; by the end of 2017, there will be a total of 27 projects,’ says Elva Escobar, from the Institute of Marine Sciences and Limnology at the National Autonomous University of Mexico.

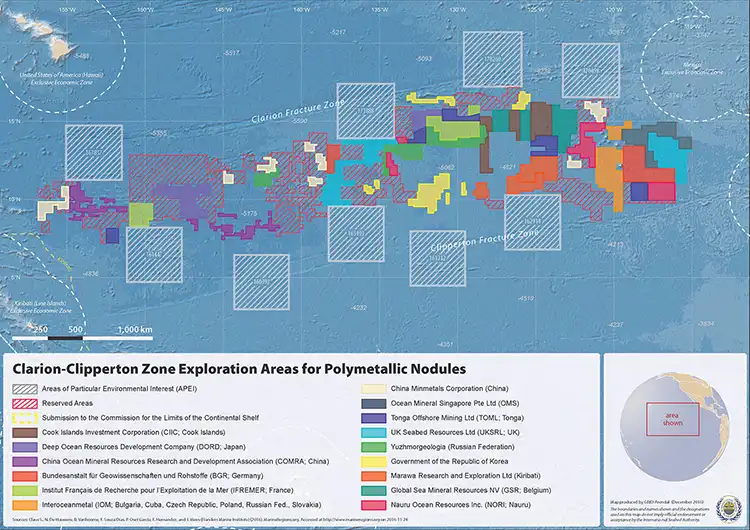

The majority of these projects are within the Pacific Ocean’s Clarion-Clipperton Zone, in-between Hawai’i and Central America. ‘Undersea deposits of metals and rare-earth elements are not yet being mined, but there has been an increase in the number of applications for mining contracts,’ adds Escobar.

Such applications are processed by the International Seabed Authority (ISA), based in Kingston, Jamaica, which is responsible under the UN Law of the Sea for regulating undersea mining in areas outside national jurisdictions.

It is the ISA’s job to determine who – if anyone – is entitled to mine for the billions of tons of manganese, copper, nickel, cobalt, and various rare-earth minerals buried far below the surface, a process often resulting in a geopolitical royal rumble as different world powers wrestle over these remote, untapped marine landscapes.

A number of marine scientists are now flagging up various environmental concerns that may occur as a result of deep-sea mining in such pristine environments, calling severe biodiversity loss ‘unavoidable and possibly irrevocable’ in a letter published in the journal Nature Geoscience.

They are now calling upon the ISA to factor such environmental damage into their considerations of mining contracts more, and generally help educate applicants on the dangers involved in deep-sea mining, and the necessary protocols that should be required for responsible mining.

‘There is tremendous uncertainty about ecological responses to deep-sea mining,’ says Cindy Van Dover, from the Nicholas School of the Environment, Duke University, North Carolina, and lead author of the letter, who points out that it can take decades or even centuries to recover from mining disturbances, if they recover at all. ‘Responsible mining needs to rely on environmental management actions that will protect deep-sea biodiversity and not on actions that are unproven or unreasonable.’

Equally, Linwood Pendleton, International Chair in Marine Ecosystem Services at the European Institute of Marine Studies, France, claims such deep-sea mining will lead to ‘an unavoidable loss of biodiversity, including many species that have yet to be discovered.’

ISA guidelines already contain several environmental requirements, such as to ‘protect and conserve the natural resources of the Area [the Clarion-Clipperton Zone], preventing damage to the flora and fauna of the marine environment’ with ‘particular attention to be paid to the need for protection from the harmful effects of such activities as drilling, dredging, excavating, disposing of waste, and constructing and operating or maintaining installations, pipelines and other devices related to such activities’.

Nevertheless, with vast swathes of the seabed potentially to become future mine sites – the largest of which will cover more than 83,000 square kilometres, roughly the size of Austria – the authors implore adequate attention be paid to an issue which may well prove to be of immense global significance.

This article first appeared on the Geographical website