Deep-sea mining could be a prime source of minerals for the future of the green energy transition – or an environmental catastrophe. Nobody’s really sure…

The future of deep-sea mining – exploiting the deep sea floor for rare mineral extracts – is being discussed at a meeting of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) in Jamaica.

The meeting has been called in response to a ‘two-year-rule‘ triggered by the Micronesian island state of Nauru, which requires the ISA to develop a governing framework of regulations for deep-sea mining should a member nation announce its intention to commence operations.

The Republic of Nauru, Kingdom of Tonga and the Republic of Kiribati are co-sponsoring the initiative to commence seabed exploitation with The Metals Company, a Canadian startup company formerly known as DeepGreen, which has announced its intention to begin mining in 2024.

The government of Canada, however, has called for the current moratorium on deep-sea mining to be extended until more is known about the impact it will have on an environment about which very little is known.

Costa Rica, France, Germany, Ireland, Spain and Switzerland have joined Canada in calling for an extension of the mining moratorium, however, China, India and Norway have come out in favour of the commencement of operations.

Related articles

Why does industry want to mine the sea-floor?

Those in favour of mining the deep-sea floor point to the necessity of extracting minerals that will be important in the transition to ‘green energy’ and the push towards Net Zero.

Cobalt, copper, manganese, nickel, gold, silver, zinc and phosphorous, used in the manufacture of everything from smartphones to wind turbines to batteries for electronic vehicles, are abundant on the deep-sea floor.

Others argue that exploitation of the seafloor will break the somewhat monopolistic control that Russia and China have over rare earth mineral extraction, and perhaps end the cruelty of child labour in the cobalt mines of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Why do people want to ban deep-sea mining?

The presence of rare earth metals and minerals in the deep sea has been known since the Challenger Expedition of 1872-1876, which first discovered the Mariana Trench, the deepest known part of the world’s oceans, measured at just under 11km deep.

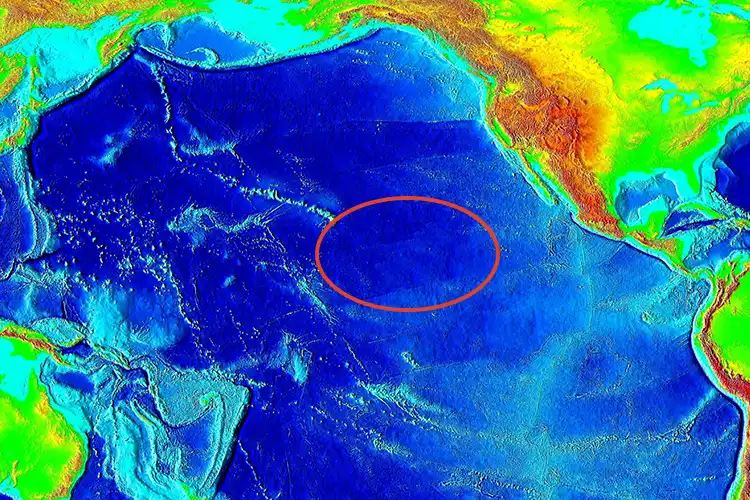

Of particular interest is an area known as the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, (also known as the Clipperton Fracture Zone), discovered by the Scripps Institute of Oceanography in 1950.

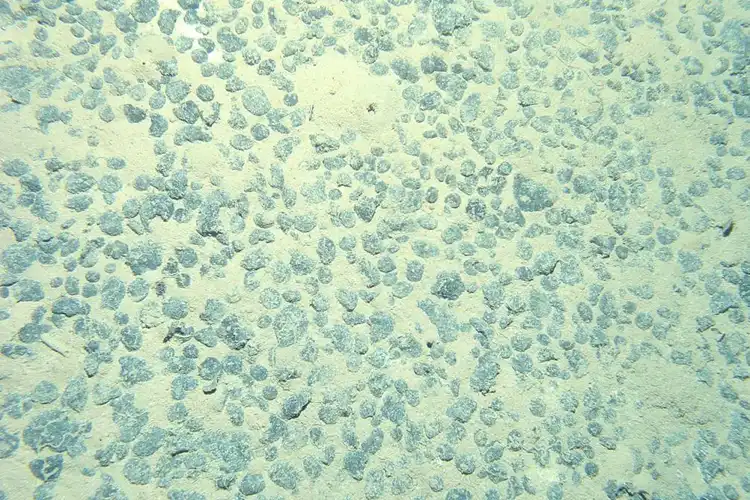

Located in the middle of the northern Pacific, the Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ) was found to be exceptionally rich in ‘polymetallic nodules’, for which the ISA approved exploratory licences, granted to governments and private businesses from across the globe.

A 2023 study by an international group of scientists, however, found that the region was populated by an exceptionally diverse range of species, many of them unknown to science.

Published in the open-access journal Current Biology, the paper records 5,142 unnamed species – and as many as 8,000 or more – of which 88-92 per cent were unidentified.

Given that little is known about these species and the environments in which they live, there is no way to determine the impact that deep-sea mining operations will have on local ecosystems, nor the wider oceanic environment as a whole.

What happens next?

The 36-member council of the ISA will debate the future of deep-sea mining on Friday, 14 July, to determine whether the existing exploratory contracts will continue, or whether commercial licenses should be granted for the extraction of minerals from the sea floor.

While the debate is likely to become heated, an ISA spokesperson said that the regulations of extraction ‘will only be approved should ISA’s members reach a consensus on its content. In the meantime, only exploration activities will be permitted.’

A UK government spokesperson said: ‘We recognise the growing pressure to extract deep-sea resources and are concerned about the potential impacts of mining activities on the fragile marine environment.

‘This is why the UK will maintain its precautionary and conditional position of not sponsoring or supporting the issuing of any exploitation licences for deep sea mining projects unless and until there is sufficient scientific evidence about the potential impact on deep-sea ecosystems, and strong enforceable environmental regulations, standards and guidelines have been developed by the International Seabed Authority (ISA) and are in place.’

- New shark-repellent hook could cut longline bycatch by more than 60 per cent - 17 February 2026

- Perth dive operator fined after leaving divers behind - 16 February 2026

- Aggressor Adventures announces upgraded Red Sea Aggressor IV - 13 February 2026