In her latest book, The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabeds, marine biologist, diver and bestselling author Helen Scales tells the stories of abyssal discoveries and warns about the consequences of the commercial exploitation of the deep. In this extract, she calls for a complete halt to deep-sea mining and fishing and for the world to come together to protect our final frontier…

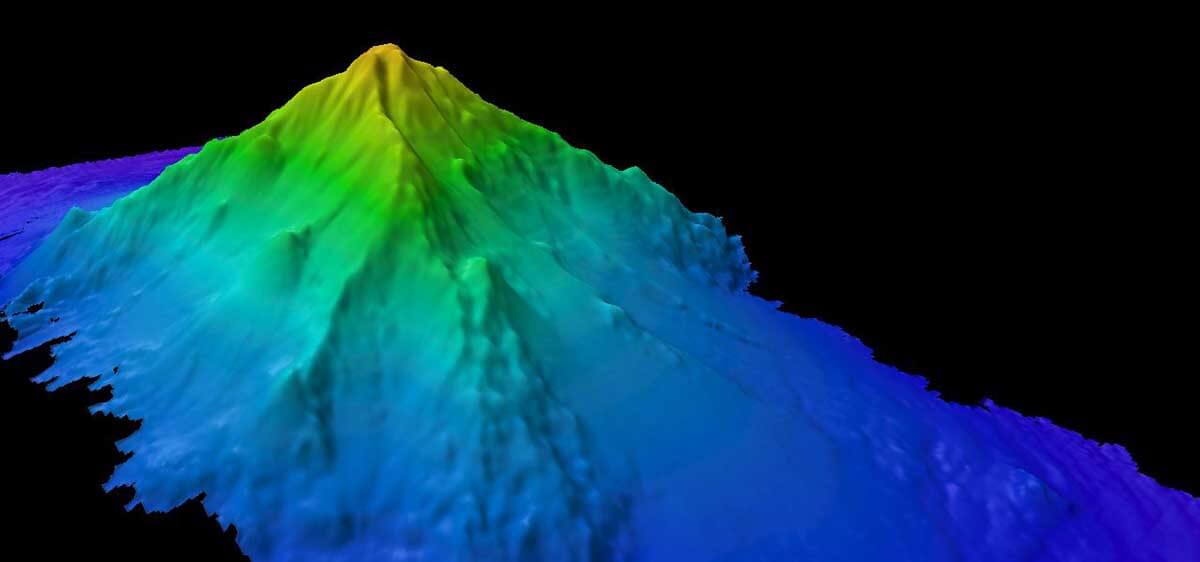

The deep is the last, vast place left on Earth to open up and exploit. Doing so would be to repeat the centuries-old story of resource extraction. Whether it is gold mines or oil wells, the near extinction of bison on the Great Plains of North America, or deep-sea trawlers destroying ancient ecosystems on seamounts, the story is essentially the same: natural resources become scarce; new frontiers are found and exploited until they too are depleted; as one frontier closes, the next opens until there is nowhere else to go.

The frontier story has always been one of destruction and loss, and increasingly it is becoming a desperate tale about the race to grab what’s left. It is naive to assume that the process would play out any differently in the deep ocean.

Everything about the deep points towards it being an impossible place for sustainable exploitation to happen. Mining activities are challenging enough to control and manage on land, so how would this be done any better in the remote, inaccessible depths of the ocean? Fisheries in the deep already contend with those same problems of control and management. In theory, it is possible to fish sustainably in shallow seas, but in practice, it rarely happens, for mostly political and economic reasons.

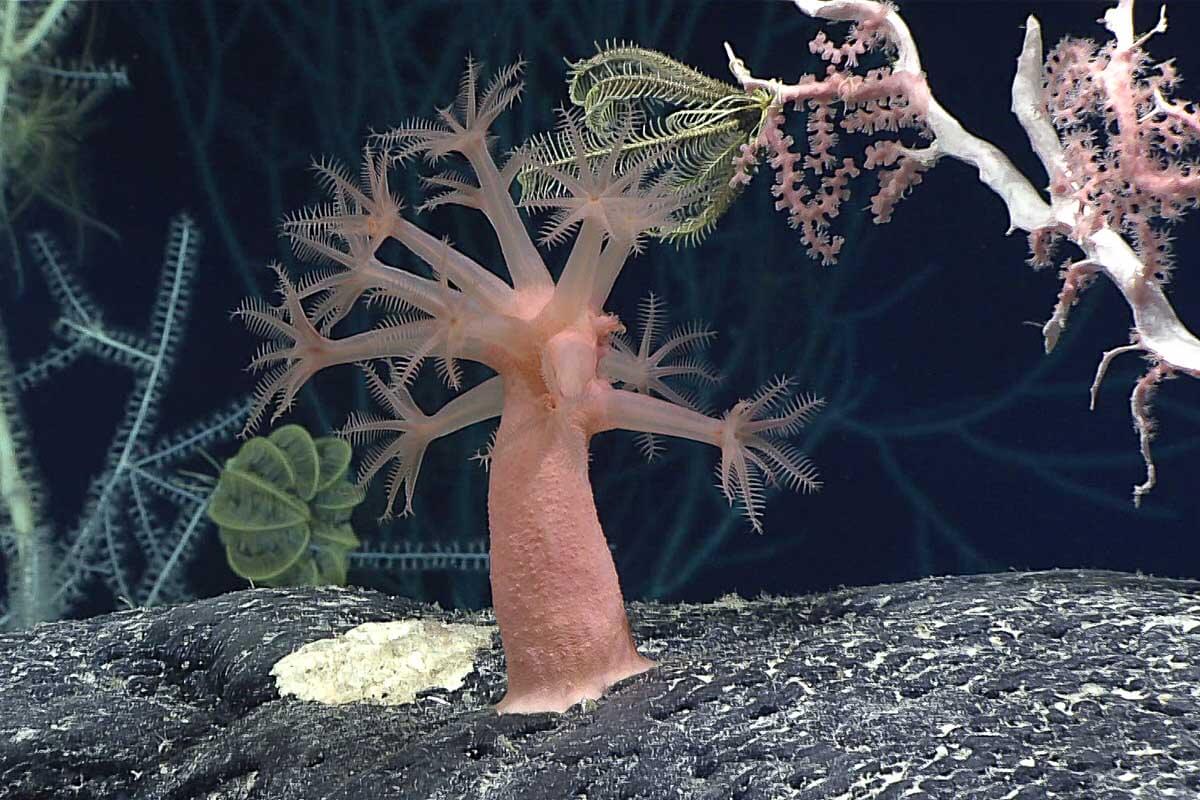

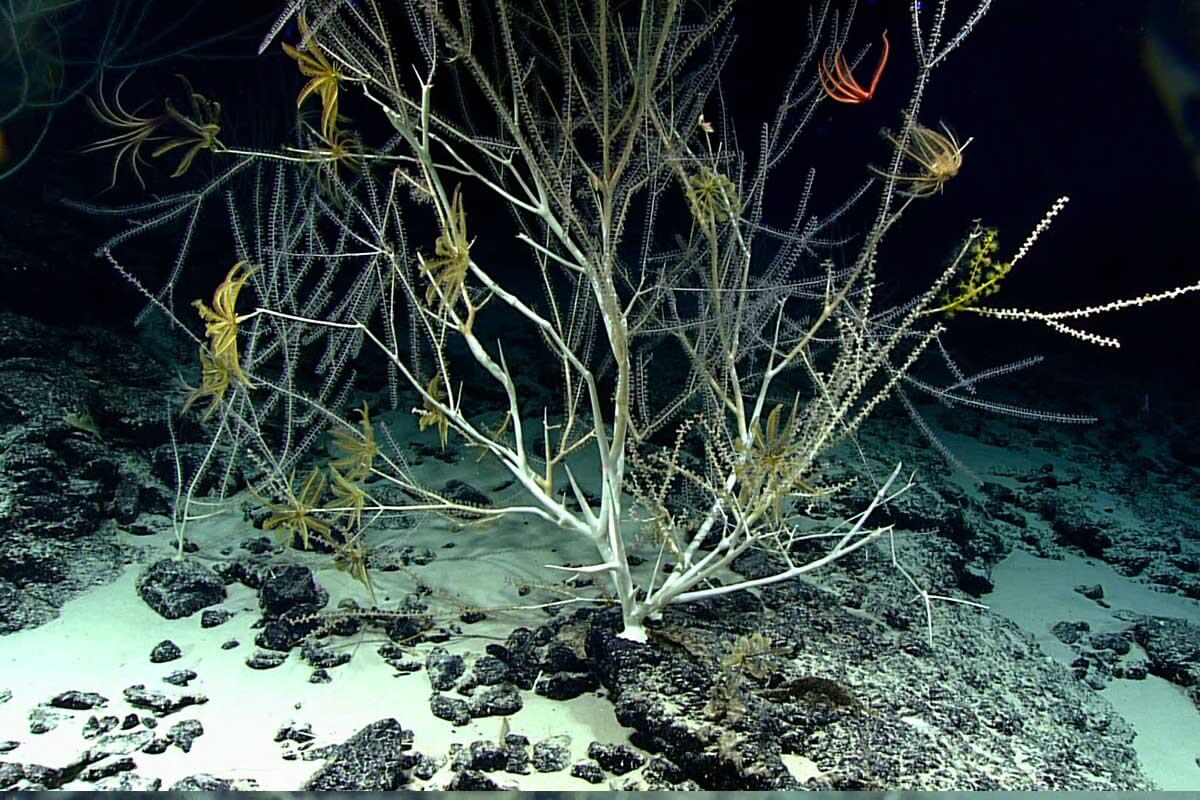

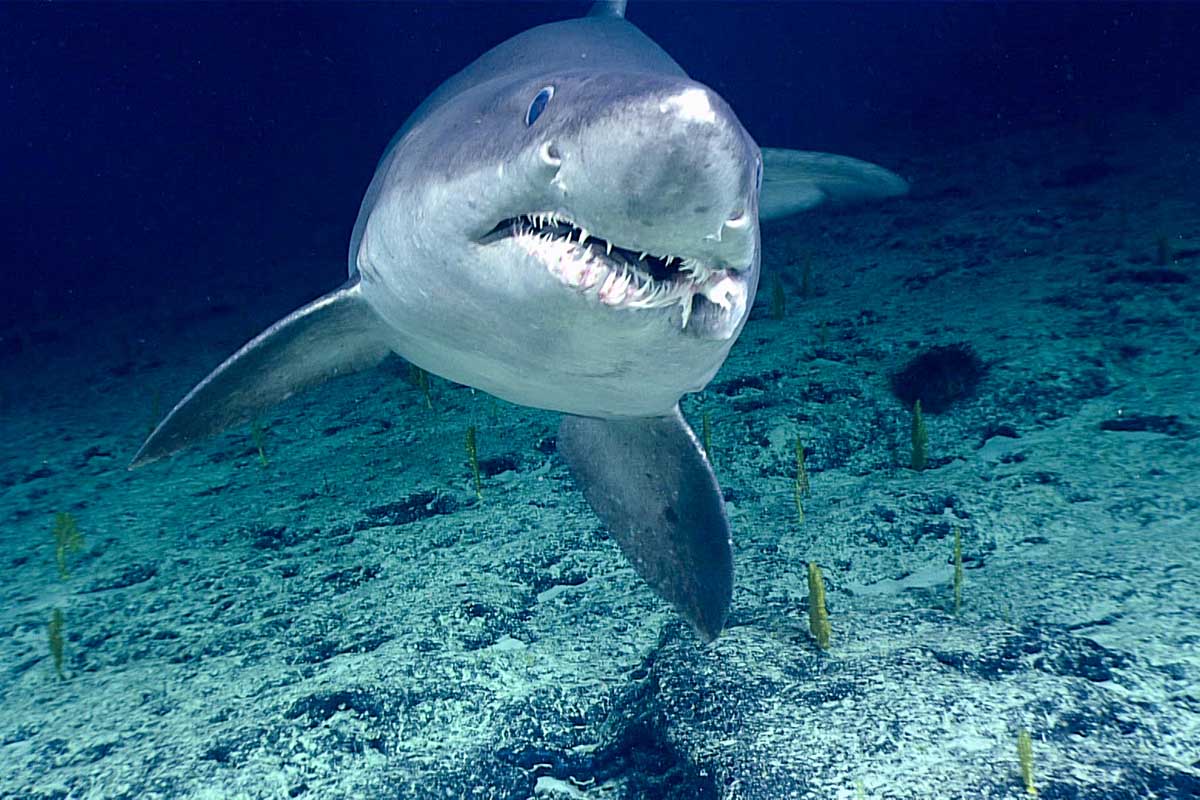

How would that dismal track record be miraculously changed for fisheries in deeper waters? Not only is enforcement far more problematic, but deep ecosystems operate in fundamentally different ways from the shallow seas: deep water fish live for hundreds of years and have relatively low reproductive rates; vital habitat is created by corals and sponges that live for millennia. The slow, hungry world of the deep is so desperately unsuited to exploitation that any semblance of sustainability would quickly tip into depletion.

Time and again, opportunities have been missed to protect the planet and its natural resources, and to find truly sustainable ways of supporting the human population. The deep sea offers an unrivalled opportunity to do things differently and write a bold, new story into the pages of human history. There are no compelling reasons for exploiting the deep, just industry and politics vying to push into that last frontier. Rather, there are strong, logical motivations to declare the entire realm off limits – no mining, no fishing, no drilling for oil and gas. From the top of the twilight zone at 200m to the deepest trenches at 20km, no extraction of any kind.

That ’s not to say that no one should go down to the Abyss and beyond. With exploitation brought to a halt, scientists would be free to continue finding out more about what lives in the deep and discovering in ever more detail how this whole intricate living system works. That includes the continued search for bioactive molecules and the inspiration for new medicines. If humans are to use the deep in any way, let it be this way; by not fishing, drilling or mining, but copying molecular ideas that stand a genuine chance of reducing human suffering and saving lives, without directly threatening the health of the planet in the process. This is a zero-sum game.

Extractive industries will erode those biodiverse ecosystems and all the medicinal riches they contain. How, then, can preservation of the deep be brought into effect? The closest precedent for such ambitious preservation is the Antarctic Treaty, an international agreement that declares the entire frozen southern continent a natural reserve, devoted to peace and science.

Just like the deep, Antarctica has no native human population, and many countries are eager to secure access to its resources, including potential reserves of oil, gas and minerals. Yet, amid various Cold War conflicts, an original group of twelve countries was able to agree to set aside territorial claims and ratify the treaty, which prohibits all military activities and all mining – at least for now. Cracks in the agreement have since started showing, as dozens more countries have signed up, and many have their eyes on resources that could become available in the future.

In 2048, it’s expected that the treaty will come up for review, which could bring an end to the anti-mining policy. In the waters surrounding Antarctica, fishing is allowed, including an increasing volume of krill fishing, which has been shown to put penguin populations at risk of going hungry. Nevertheless, Antarctica remains the most pristine continent, surrounded by the least exploited ocean, and – just like the deep sea – is uniquely sensitive and plays a critical role in the global climate. To weaken its protection would be a grim pronouncement for the future of the planet.

The deep ocean needs decisive, unconditional protection, and one way to begin is within the countries already involved in deep-sea fishing and in buying and prospecting the abyss. These include Australia, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, China, Cook Islands, Cuba, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Faroe Islands, France, Germany, Iceland, Japan, Kiribati, Latvia, Lithuania, Nauru, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Singapore, Slovakia, Solomon Islands, South Korea, Spain, Tonga, United Kingdom and United States.

If you live in one of these countries, you can put pressure on your government to divest itself from those extractive industries. If you are a citizen of one of the 168 members of the International Seabed Authority, including the European Union, then you can call on your government to fully implement the environmental protections for the deep seabed required under the Law of the Sea. You can support NGOs that are campaigning for stringent protection of the deep and to bring seabed mining and deep-sea trawling to an end.

Consumers of seafood can pay attention to what’s on the label, learn where species live and how they are caught, and refuse to eat any animals, and their by-products, that come from the deep ocean. You can take any opportunity to learn about the deep and its hidden living wonders, care about them, talk about them, help make them as beloved and cherished as more familiar animals and wild places on the planet.

Preserving this realm takes place not just within the deep itself. Plentiful food can be harvested sustainably from shallow seas by targeting species that swiftly reproduce and replenish, by adopting fishing techniques that don’t wreck ecosystems, by halting bycatch of unwanted species, by eliminating harmful subsidies to fishing industries and by farming low-impact species of shellfish and seaweed that come with the added bonus of capturing carbon from the atmosphere.

Achieve truly sustainable fishing and seafood farming in the surface, sunlit zone and there would be no need to even consider whether the deep seas can feed the world, because the shallows would already be doing so, supported by intact food-web links weaving through the deep and by the nutrients welling up from healthy waters thousands of metres below.

Pollutants sinking into the depths, from carbon to PCBs, come from human activities on land and in surface seas, that much is glaringly obvious. Sources of plastic and other forms of chemical pollution need to be identified, and their escape into the environment minimised and wherever possible stopped altogether. Emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases must be drastically cut.

What’s keeping us from achieving the goal of a low-carbon global economy is not a limited supply of metals to make wind turbines, solar panels and electric cars – it is the political will to make the transition happen. Urgent action requires large-scale governmental spending: to invest in renewable technologies, ones that don’t rely on seabed metals; to move innovative zero-emission vehicles from laboratories to the roads; to develop circular economies that reuse and recycle materials; to support innovations that will improve efficiencies in the resources which we already have access, instead of opening up new frontiers. The 2020s is the decade when all of this must happen – otherwise humanity will surrender itself to the worst possible version of the climate crisis.

Any of us can decide to become an active part of that transition towards a new way of doing things, and a future that doesn’t necessitate the exploitation of the ocean depths and lead to the hastening collapse of ecosystems and climate. Demand better of your elected officials. Protest, if you wish. Show what’s possible, in any way you can. Say no to single-use plastics and be part of reshaping a society that has the aspiration and wherewithal to mend, fix and make things last.

You can choose to fly less, drive a smaller car, or have no car at all, and step off the endless treadmill of mass consumerism. And if you can’t find the better, ethical options you want, then ask why and urge corporations to provide them. It becomes more than just a matter of protecting the deep ocean. The same kinds of initiatives that protect the rest of the planet, directly protect the hidden deep by removing any need to exploit it. ■

Copyright © Helen Scales 2021. This is an extract from The Brilliant Abyss: True Tales of Exploring the Deep Sea, Discovering Hidden Life and Selling the Seabed, published by Bloomsbury Sigma at £16.99 (hardback).