Concern growing for coral reefs and other aquatic species as global ocean temperatures reach the highest-ever recorded

The highest average ocean temperature ever recorded was reached at the end of July, according to data from EU’s climate change service, Copernicus, sparking concerns for the health of coral reefs and other aquatic life across the globe.

The average global sea surface temperature (SST) reached 20.96°C – breaking the previous record of 20.95°C set in 2016 – the highest reported average SST since records began.

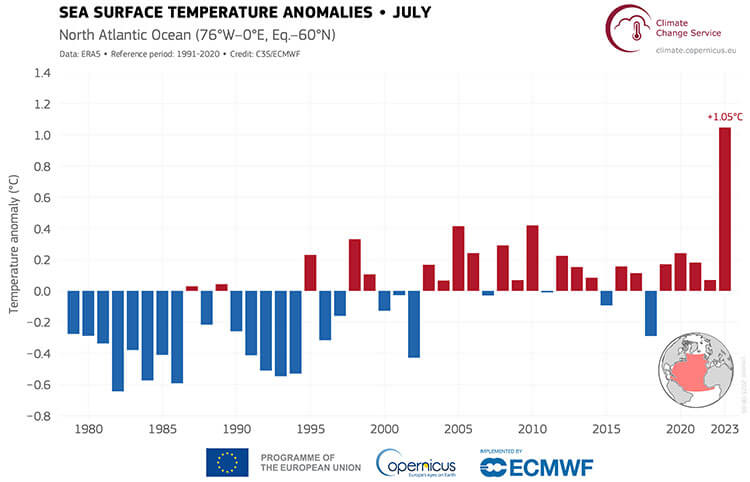

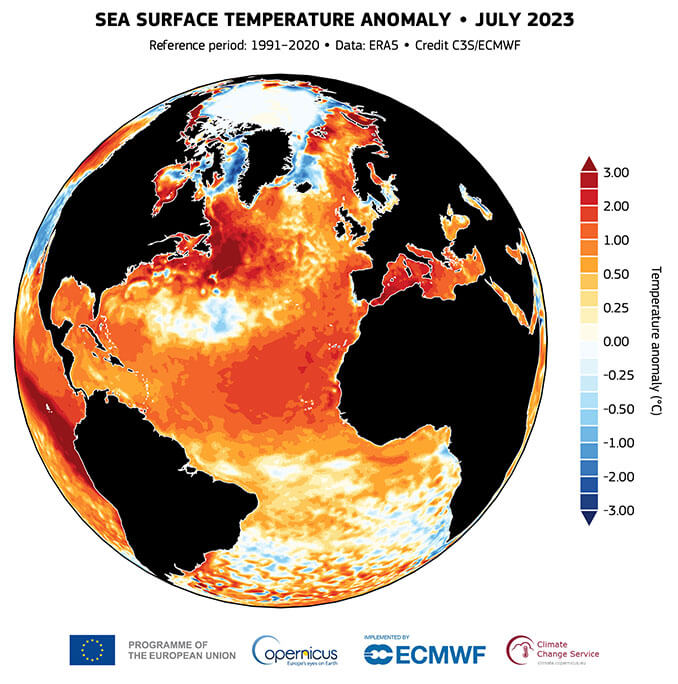

Unusually high temperatures have been recorded for several months, including a recent marine heatwave in the North Atlantic which brought average ocean temperatures close to the previous record set in 2022, and water temperature around the coast of the UK and Mediterranean reaching more than 5°C above the seasonal average in some locations.

More ocean temperature-related articles

The increase in SST coincides with the onset of the latest El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO), the recurrent sea surface temperature warming of the eastern Pacific Ocean, and one of the largest impactors of the global climate system.

This year’s El Niño is the first in seven years, and – still in its early days – is causing concern among some scientists that this year’s ocean warming may continue, as the highest average global temperatures are usually reported in March, following the southern hemisphere’s summer.

What is the impact of rising ocean temperatures?

Much life in the ocean is temperature dependent. As most fish are cold-blooded, they are capable of surviving within a limited range of species-specific temperatures. Changing water temperatures can have both a detrimental effect on the animals’ health, and also cause them to change the area of ocean which they inhabit.

A change in the distribution of predatory fish and their prey can have a knock-on effect on the species both above and below them in the aquatic food chain, which in turn may impact the presence of plankton and algal blooms, themselves both heavily influenced by local water temperatures.

Most commonly reported is the bleaching of coral reefs, during which a rise in temperatures causes the reef-building coral polyps to eject the zooxanthellae dinoflagellates (algae) that provide them with nutrients and also colour, exposing the white stony exoskeleton secreted by the corals beneath.

While bleaching is a natural phenomenon from which coral can – in normal circumstances – recover within a few weeks, extensive, repeated mass bleaching events caused by extended elevations in temperature often result in coral mortality, from which the reef can take decades to recover.

The subsequent loss of habitat, protection and food source is devastating for the many thousands of creatures – from nudibranchs and sponges to turtles to sharks – which rely on the reefs to survive.

Mass bleaching in 2016 along the Great Barrier Reef resulted in an estimated 22 per cent coral mortality with further bleaching events happening in 2017, 2020 and 2022 – the last being especially significant as it happened during a La Niña event, the cooling phase of Southern Oscillation, when water temperatures should remain cool and have less impact on the reefs.

The record-breaking temperatures of 2023 have led to bleaching events across the Florida Keys, the world’s third-largest barrier reef system with – at the time of writing – NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch maintaining the highest ‘Level 2’ bleaching alert for the region.