Immersion pulmonary oedema (IPO) may well be the cause of a significant proportion of scuba diving fatalities, and people with high blood pressure are particularly at risk. Mark ‘Crowley’ Russell reports on how some divers may be sleepwalking towards disaster – a subject very close to his own heart

I woke up on the morning of 28 April 2019 as immortal as I had been since I was a teenager. I went to work, had dinner, popped outside for a smoke, cracked open a beer and sat down to watch TV, just as I did every day.

I was two weeks away from a trip that would have taken me back to the Great Barrier Reef for the first time in a decade; but as I sat there, beer in hand, I began to feel decidedly unwell. I was sweating more than a late-spring evening should merit. My hands were clammy, my pulse was racing, and with a rising sense of panic in my chest, I asked my mother to take me to the walk-in centre at the local hospital.

The nurse took one look at the portly, middle-aged smoker standing in front of her and put me down as a prime candidate for a heart attack. Within five minutes I was triaged by ECG, wheeled through to the emergency ward and hooked up to a machine that didn’t so much go ‘ping’ as ululate the most dissonant of cacophonies every time my blood pressure soared into the danger zone. Which it did every 60 seconds, because my blood pressure was spiking at 244/148mmHg.

‘Normal’ blood pressure is considered to be between 90/60mmHg and 120/80mmHg. High blood pressure is considered to be anything over 140/90mmHg. My blood pressure was in crisis territory. Tests results showed I had not had a heart attack – but I was definitely no longer immortal.

On the whole, I consider myself to be extremely fortunate. I went to the clinic feeling unwell, and was discharged with a diagnosis of serious hypertension and a prescription for a lifetime of medication. Had I gone to Australia, however, the outcome might have been substantially less favourable.

A colleague who took my place on the trip reported that some of the diving had been quite challenging, in particular the cool water and strong currents around the wreck of the SS Yongala. Had I made that dive, my uncontrolled high blood pressure would have put me at great risk of Immersion Pulmonary Oedema, a build-up of fluid in the lungs caused by immersion in water which makes it difficult – eventually impossible – to breathe. IPO (IPE for the US spelling of Edema) is thought to be responsible for a significant percentage of scuba diving fatalities, but little is known about the condition among the global scuba diving community.

Signs and symptoms of IPO in scuba divers

- Breathing difficulties including rapid, heavy or uneven breathing, or coughing uncontrollably, when not exercising strenuously

- Confusion, swimming in the wrong or a random direction

- Inability to carry out normal functions, while appearing to have to concentrate on breathing

- Belief that a regulator is not working properly, or indicating one is out of gas when they have an adequate supply

- Rejecting an alternate air source

- Indication of difficulty of breathing at the surface.

- Uncontrollable coughing at the surface accompanied by frothy sputum which may contain blood

The silent killer

The primary cause of Immersion Pulmonary Oedema is high blood pressure, also known as hypertension, a very common condition but one that is very much misunderstood. It is not solely the preserve of the obese and the unhealthy; it affects both men and women in equal measure; and many people have no idea that they have it. Dr Doug Watts is medical director for DDRC Healthcare, a charitable organisation based in Plymouth, UK, which is dedicated to diving medicine and safety. ‘It’s a common misconception with blood pressure that it causes symptoms,’ said Dr Watts. ‘Unless it’s very, very high, it’s completely asymptomatic. And so, therefore, it’s seen as this “silent killer”’.

Long-term hypertension stiffens and damages arterial walls, making it easier for cholesterol deposits (plaques) to build up and narrow the coronary arteries, increasing the risk that the supply of oxygenated blood to the heart will be interrupted should the plaque rupture and cause a blood clot to form. Sustained hypertension also weakens the heart muscle itself, making it more difficult to pump blood around the body, and increasing the threat of a cardiac event.

The risk that a person will have a heart attack while scuba diving is no greater than the risk that they would have one at the surface, but the outcome is likely to be much worse if they do. The victim may aspirate water and drown, first aid is virtually impossible until the diver is removed from the water, and medical services may be several hours away.

‘[High blood pressure] is part of your overall cardiovascular risk, which can be reduced by bringing it down,’ said Dr Watts. He explained that an individual’s cardiovascular risk needs to be considered over a period of ten years into the future, and that it varies according to age, cholesterol levels, gender and family medical history. He added: ‘We want to reduce the risk of having a heart attack for everyone, and your blood pressure is part of that.’

‘Acute cardiac events’ are among the most prominent causes of scuba diving fatalities. The Divers Alert Network (DAN) 2019 Annual Diving Report lists 228 scuba and breath-hold diving-related fatalities during 2017. Of the 29 (20 scuba, nine breath-hold) for which autopsy data were available, ten scuba and six breath-hold deaths were recorded as acute cardiac events.

Similarly, of the 13 casualties recorded in the 2019 British Sub-Aqua Club (BSAC) Diving Incident Report, two were confirmed by autopsy to have been caused by a cardiac event, but as many as nine of the others showed indications that the divers had a ‘significant pre-existing medical condition’ What ultimately led to their deaths may never be known, but Immersion Pulmonary Oedema is increasingly being considered as a likely culprit in many diving fatalities – perhaps, even, the most common killer of scuba divers and swimmers in the world.

The unknown suspect

Over the past few years, BSAC has begun trawling through its extensive database of scuba-diving incidents looking for cases where Immersion Pulmonary Oedema may have been involved, based on information available in the incident report but which was not recognised as IPO at the time. BSAC reported that 24 cases of IPO (not all fatal) had been confirmed between 1997 and 2018, but as of its latest 2020 report, the club has found a further 160 incidents where IPO is suspected as being a factor.

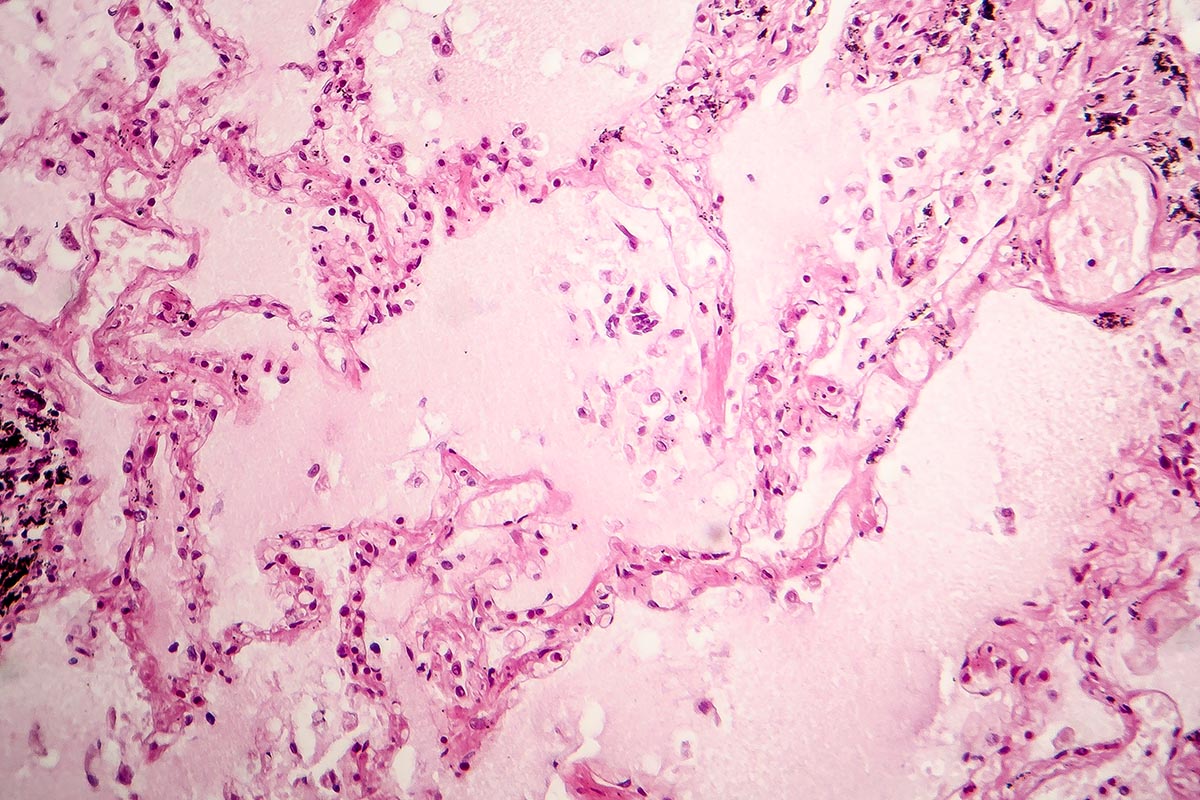

IPO occurs when an increase of pressure in the pulmonary capillaries forces fluid into the alveoli, the microscopic air sacs in the lungs where gas exchange during respiration takes place. That pressure increase is caused by immersion in water, especially cold water, and is made worse by pre-existing hypertension. The problem is not unique to divers, but to all people who enter the water, and is of particular concern for triathletes during the swimming phase of a triathlon

Research into IPO was instigated by Dr Peter Wilmshurst, a UK-based consultant cardiologist and medical referee for the UK Diving Medical Committee (UKDMC), who first described the condition in 1989. Since then, Dr Wilmshurst has dedicated much of his time to bringing the phenomenon to the attention of the scuba diving public.

‘When you get into the water, you divert blood from your legs and periphery centrally, so that puts up the capillary pressure just by virtue of you being immersed in water.’ explained Dr Wilmshurst when I queried the mechanism by which hypertension leads to IPO. ‘But also, when you’re breathing underwater – or with your head out but your chest below water – you’re actually breathing with a greater suction, to suck fluid into the alveoli. ‘Those two things tend to cause IPO, but the risks go up with age and high blood pressure, and the colder the water, and if you’ve taken excess fluid on board before the dive.’

‘When you jump into cold water, you become vasoconstricted (your blood vessels narrow) and your blood pressure automatically increases,’ Dr Wilmshurst continued. ‘If you’ve got high blood pressure to start with, going into cold water is even worse because you’ve got additive effects.’

There are several problems related to Immersion Pulmonary Oedema which make it difficult to detect, both in the aftermath of a fatality and during the incident leading up to it. Since IPO forces the fluid into the lungs, if a diver should succumb to IPO underwater and be rendered unconscious, it is likely their lungs will fill with water and their death attributed to drowning. Signs that a diver is suffering from IPO include shortness of breath, excessive inhalation and bubbles, and a mistaken belief they are having an out-of-air incident, which may be attributed at the time to an equipment malfunction, rather than a medical emergency.

Unfortunately, these signs and symptoms are rarely taught to the general public, and they can happen to anyone, regardless of personal level of fitness. Overexertion during a dive will raise the blood pressure of even the fittest individual, but a diver who is unfit and overweight will become overexerted more easily; is more likely to be hypertensive and at greater overall cardiovascular risk; and therefore having to fight against an unexpected current or excess negative buoyancy can become life threatening for that individual.

Steps towards prevention

One organisation with a particular interest in trying to bring down the number of avoidable diving emergencies is the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI), which responded to 44 of the 271 total UK diving incidents in 2019. Since 2016, the RNLI has been placing Wellpoint machine health kiosks at popular UK dive spots and shows, to encourage divers to check their potential cardiac risk.

‘We’ve got divers who are very well trained and very experienced, who are going diving and don’t know they’re at high risk,’ said Nick Fecher, of the RNLI’s Water Safety Delivery Support team, ‘and we’re trying to get through to those individuals that we’re not trying to stop them from diving, we just want them to go in with their eyes open, to know the risks and be able to mitigate those risks.’

The machines measure the blood pressure, heart rate, height, weight, internal body fat, age and BMI of the patient, and ask a series of questions about the user’s medical history, before printing out an overview of their risk of experiencing a cardiac event in the next ten years.

To date, the machines have conducted 8,837 tests, 4,303 of which were on divers. From the data collected, three per cent of tests – 151 males and 11 females – reported the user as being at high risk from having a cardiac event in the following ten years.

The figures suggest men have a significantly greater cardiovascular risk than women, but the numbers are skewed because there have been historically more male divers than female, particularly in the early days of the 1980s and 1990s. Among the general population, men are twice as likely to have a heart attack as women, but there is little difference between genders in the prevalence of hypertension, and women – for reasons that remain unknown – are eight times more likely to experience IPO than men.

The cohort of divers that learned to dive during that period now presents an increased concern for IPO, as blood pressure rises and cardiovascular fitness declines with age. BSAC’s 2019 report lists the average age of diver fatalities as 58.2, and since 1998 the average age of all UK divers recorded in the incident database has risen from 35.8 to 43.6. DAN reported that two-thirds of all fatalities in 2017 were divers over the age of 50.

‘We have this older bubble of divers going through the system, and these are the ones who are susceptible to cardiac issues,’ said Nick. ‘I’m not sure we’re going to see a reduction in cardiac events underwater in the next few years, but hopefully, some people who were at high risk have taken action because of our campaign.’

Causes of IPO

• High blood pressure (or other pre-existing cardiovascular problem)

• Cold water

• Excessive hydration prior to a dive

• Overexertion during a dive, regardless of fitness level

• Stress

Pressure check

The results of the RNLI’s campaign show that this inevitably is going to be a growing problem among the diving population as more people are certified, and they in turn grow older. Meanwhile, ongoing research into IPO is altering the recommended limits for ‘safe’ blood pressure, and most divers – including myself, up until recently – probably have no idea what that is.

The current recommended maximum blood pressure reading at which divers are advised to seek treatment is now 135/85mmHg, where previously anything up to 160/95 might have been considered acceptable for an established diver. There are some who think this is too low, because it falls under the standard limit of 140/90 for the medical definition of high blood pressure. However, the impact of immersion, particularly in cold water, gives the lower level more significance.

Checking your blood pressure can be done by a GP, at a pharmacy and even some department stores, but a single reading is not necessarily informative, and blood-pressure readings taken in clinics are often elevated due to ‘white coat hypertension’ caused by worry or nervousness of patients in a medical setting.

‘A one-off reading isn’t hugely important, because your blood pressure goes up and down according to how much adrenaline you’ve got in your body, how stressed you are, whether you’ve had some caffeine that morning, etcetera,’ said Dr Watts. ‘It’s your blood pressure with an average of measurements that is relevant. So, if you’ve got a blood-pressure reading that’s high in the clinic, your GP may ask you to have some blood-pressure readings done at home.’

A reliable home-monitoring device can be bought from as little as £20, and any diver who might be considered at risk – overweight, unfit, over 40, a smoker, to name just a few possible indicators – would be well advised to get one. High blood pressure is treatable, and having it does not necessarily mean an end to diving – but it is wise to seek the guidance of a diving referee, make changes to your lifestyle and diving environment to mitigate the risk, and understand that there may be underlying conditions which do indeed call time on your diving career.

Treatment for IPO

A diver suffering from Immersion Pulmonary Oedema needs to be surfaced and removed from the water as quickly as possible. Be aware that they will be hypoxic, and as they surface and the partial pressure of oxygen in their lungs drops further, they may pass out during the ascent. Hold their regulator in their mouth with light fingertip pressure, if applicable and appropriate.

Once out of the water:

- Keep the diver sitting still and upright if they are conscious – do not lie them down.

- Keep the diver warm to maintain blood flow

- Administer 100% oxygen

- Do not administer fluids

- Seek emergency medical assistance

Sleepwalking

There are two particular moments that stand out in my mind from my own personal experience. When I was waiting in the emergency ward with the blood pressure machine alarm sounding every 60 seconds, one of the nurses stopped to check on me and said, ‘I wouldn’t worry too much, loads of people have blood pressure like that. You’ll have to take pills from now on, but you’ll be fine.’

The second was at a later appointment where I had a CT angiogram, during which a catheter is threaded through the wrist to the coronary arteries for a close-up inspection of the build-up of plaque within. One of my ward-mates was a chap in his early sixties, quite clearly a fit and healthy individual, with a lean and muscular sportsman’s frame. As I was waiting to be discharged, I overheard the cardiologist inform him that he would be referred, as a matter of urgency, for a triple heart bypass. I, on the other hand, with my soft and pudgy body, was given some pills and sent home. It doesn’t matter who you are; it can happen to anyone.

Thousands of divers are sleepwalking into the realms of Immersion Pulmonary Oedema, and other cardiovascular problems, but we can mitigate that risk by having our blood pressure checked regularly, taking adequate steps to improve our personal fitness and cardiovascular health, and by seeking medical advice from a diving specialist should we be diagnosed with a condition that might cause problems underwater.

Such a diagnosis does not necessarily mean an end to diving, but it would be foolish to keep diving should we be advised not to.

As for me, I’m in a lot better shape. I’ve quite smoking, changed my diet, shed 18kg and my medicated blood pressure is stable around the 120/80 mark, but the pandemic prevented me getting medical clearance to go diving. I may never dive again – but the Australian Coast Guard didn’t have to pull my body off the SS Yongala, so I’ll take that as a win.

DDRC Healthcare charges £5 in the UK for a telephone consultation: www.ddrc.org. To find an approved medical referee in your area visit www.ukdmc.org