Jo Caird explores the dramatic underwater landscape of Tenerife in the Canary Islands, with Photographs by Steve Pretty

By Jo Caird

Bright blue light filtered down through the hole in the ceiling. I switched my torch off and let myself be pulled gently to and fro by the swell, basking in the otherworldly glow inside the flooded lava tube. The site was El Tubo, a 150m-long tunnel through basalt rock a short zodiac ride from the village of Garachico on Tenerife’s northern coast.

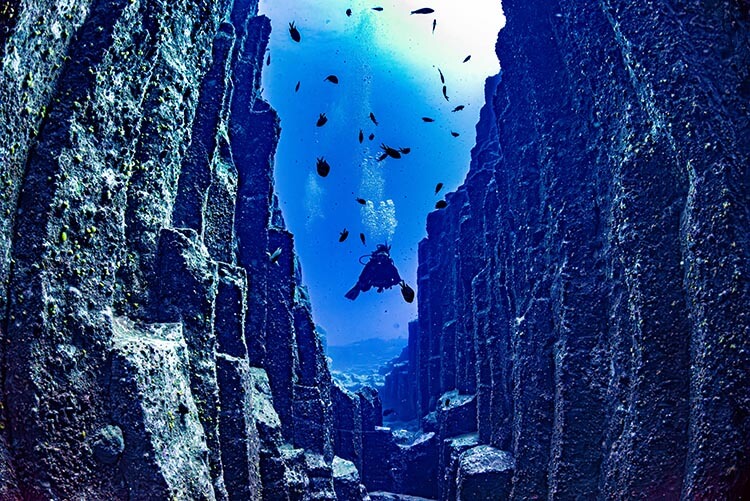

There was too much swell to access the tunnel through its small entrance at 12m. Instead, we’d headed straight to the exit, a cathedral-like cavern, opening out at a depth of 20-30m in the midst of a remarkable landscape of columnar basalt.

Having descended on the anchor line, we crossed a shelf of rock that dropped away after a short distance down a series of basalt column steps akin to those at the Giant’s Causeway in Ireland.

Turning to the south, the mouth of the tunnel came into magnificent view, the light from the distant ceiling hole illuminating the gloom. Marine life was limited – a few sponges of various shapes and colours on the walls, and some small silver fish I couldn’t identify swimming near the floor of the cave – but that didn’t matter.

You don’t come to Tenerife for enormous shoals of fish or abundant invertebrates. You come for the spectacular landscapes, both above and below the surface, the product of millions of years of volcanic activity on this archipelago off the northwest African coast.

El Tubo, thought to date back to an eruption tens of thousands of years ago, long before Tenerife was first settled by the Guanche people around the first millennium BCE, certainly delivers.

Topside, Garachico still bears the scars – both geological and economic – of a much more recent eruption. In May 1706, lava poured down the flank of the Trevejo volcano into what was then Tenerife’s most prosperous port town, filling the harbour. With trading vessels bound for Europe and the Americas now unable to dock in Garachico, the commercial centre shifted first to Las Americas in the south, and eventually to Santa Cruz to the east.

A huge new harbour opened to the east of Garachico old town in 2012, paid for with EU funds, but it’s hard to imagine that the town could ever regain its 17th-century status. The lava that did so much damage is still visible today in the old harbour and in a series of beautiful natural swimming pools that sit alongside it.

Garachico may not be a heavy hitter in economic terms these days, but it’s certainly a charming spot to visit and dive. The 1706 eruption was one of a handful that have taken place on Tenerife in the years since the conquest of the Canary Islands by Spain in the 15th century (the beginning of written records on the islands). As in Garachico, you can find evidence of this recent volcanic activity in the landscape, but as a diver visiting Tenerife, it’s the much more ancient volcanism of the island that takes your breath away.

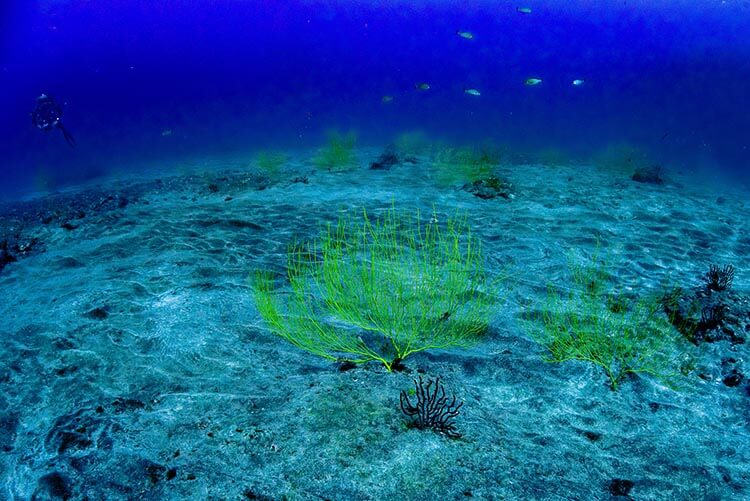

At La Rapadura, for example, a site a 15-minute zodiac ride northeast of Puerto de la Cruz, two enormous basalt pinnacles tower over a third pillar lying horizontally on the seabed at 36m. So uniform and deliberate are these columns of rock that, swimming among them on my way to find an unlikely garden of neon-yellow gorgonian sea fans at 38m, I could have sworn they were man-made.

Not only are these formations entirely natural – a result of very particular cooling conditions – they were also, originally deposited on land, according to Professor Valentin R Troll, the joint author of The Geology of the Canary Islands with J C Carracedo. ‘Sea level rise since the last glacial maximum some 20,000 years ago has drowned them,’ he explains.

However they got there, they make for an extraordinary dive, particularly taken together with the towering cliffs you pass on your way to reach them. The result of coastal landslides that took place millions of years ago during the formation of the island from three separate volcanoes, these cliffs tell a story, for those who know how to read it, of the island’s volcanic past. Each horizontal stripe of paler rock indicates an ancient lava flow event, adding to the gradual process that saw Tenerife take shape.

The cliffs at Los Gigantes, on the northwest coast of the island, are more impressive still, soaring 600m above sea level and cut through with vertical stripes of rock that reveal the course of magma on its way to the surface long ago. At their base, ten minutes by boat from pretty Los Gigantes harbour, is Barranco Seco.

With its combination of rough basalt formations harbouring morays, shrimp and scorpionfish; a sand patch that is home to garden eels and schooling bastard grunts; and a glorious natural amphitheatre, it’s a dive site that perfectly characterises the Tenerife scuba experience.

La Atlántida, on the other side of the harbour, offers a similar picture, with the addition of some weirdly twisted basalt columns and a couple of yellow gorgonians. While those formations are probably a combination of ancient landslides with more recent lava flow on top, suggests Professor Troll, it’s a different story in the south of the island.

The breathtaking geology at El Arco, off Montaña Amarilla – a towering archway that seems to come out of nowhere as you swim alongside a high 180-degree wall – could date back to a large explosive eruption of the now extinct Las Cañadas volcano some 180,000 years ago (you can still see its caldera at the centre of the island, the newer Teide volcano inside it).

The archway and the astonishing canyon you reach a little way on from it are what’s left after millennia of erosion, a process that was very evident on the day of my dive at El Arco, the swell through the narrow break between the rock walls making for an exhilarating ride.

Tenerife diving isn’t just geology: I had fun zipping out to the El Peñón wreck on a dive scooter, admired the schooling barracuda at Robert Reef and marvelled at butterfly rays at the very popular El Bufadero site near Los Cristianos. But it’s the thrill of exploring a volcanic landscape that has stayed with me; a landscape millions of years in the making that has been taken by the sea.

Jo Caird and Steve Pretty travelled as the guests of Turismo de Tenerife, staying at Hotel Playa Sur (hotelplayasurtenerife.com) and diving with Ocean Friends Buceo Y Apnea (oceanfriendsdiving.com), Diving Angel (www.diving-angel.com) and Macaronesian Divers (macaronesiandivers.com).

More great reads from our Magazine…

- Battle of the Colours – the mating ritual of giant cuttlefish

- Mexico’s Manatees – the Sirens of the Caribbean

- DIVE’s Big Shot Kaleidoscope – the winners!

- How the Marine Megafauna Foundation makes sustainability sustainable

- Over & Under – the unique effects of modified digital lenses underwater