For five years Jeremy Brown had been trying to photograph the stunning bioluminescent courting display of a tiny Caribbean crustacean. He succeeded when he witnessed this Halloween light show diving in Bonaire

Words and pictures by Jeremy Brown

It was 45 minutes after sunset on Halloween and I could just make out my dive buddy hovering next to me in near-complete darkness. Then the first one appeared, a spiral of ghostly blue points of light that drifted in the water column for a few seconds before dissolving into the night.

This was not some supernatural will-o’-the-wisp apparition, but the bioluminescent mating display of a male cypridinid ostracod, a tiny unassuming crustacean the size of a flea. A few more spirals appeared over the next five minutes, beautiful but hardly the light show I had been hoping for. These displays are light-sensitive and only occur far away from human-generated artificial light. Just as I was beginning to think that eleven days after the full moon might have been too late for a good display, my wife Alex signalled me with her torch.

The handful of ostracods displaying in front of me instantly went dark when her torch beam hit them. She swept her torch over the soft coral sea fans behind her and the same thing happened, only this time it was different. Seconds after she switched off the light, thousands of ostracods resumed displaying, in a glorious synchronicity.

It was absolutely stunning – a light show like no other. We were surrounded by thousands of pulsating blue dots of light. Male ostracods leave a trail of glowing chemicals in the water column to lure up from the seafloor females ready to mate. More than 70,000 species of ostracod have been identified in oceans and fresh water and it had been noted that some species luminesce – it was thought to deter predators. It was only in the 1980s that American marine scientist James Morin realised that the males of a relatively small number of cypridinid ostracod species found in the Caribbean also put on a complex light show to attract mates.

Related articles

I had first witnessed this haunting, and very beautiful, display on the Caribbean island of Bonaire in 2016, and have been determined to photograph it ever since, returning in 2019 and 2021 with that express purpose.

I’ve learned something new on every dive with these captivating little crustaceans and my tenth attempt on Halloween 2021, was no exception. On that night my camera and tripod, which I had carefully positioned on a patch of bare sand earlier in the evening, were pointing in completely the wrong direction and I dared not reposition them in the dark for fear of damaging the reef.

I should have been enjoying the show, instead, I was contemplating whether the simpler composition I had already taken a few nights previously would be enough for me to lay claim to getting the first-ever publication-quality photographs of this spectacular event.

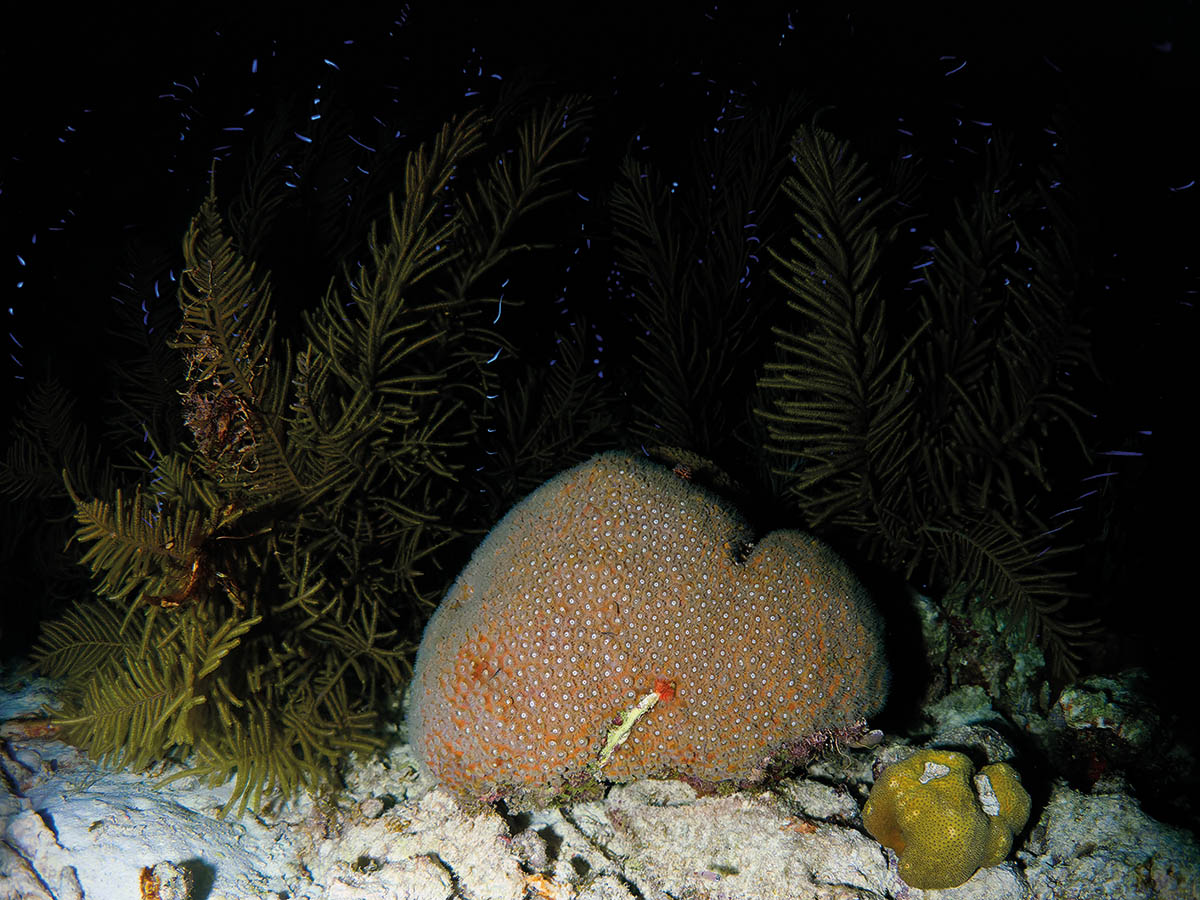

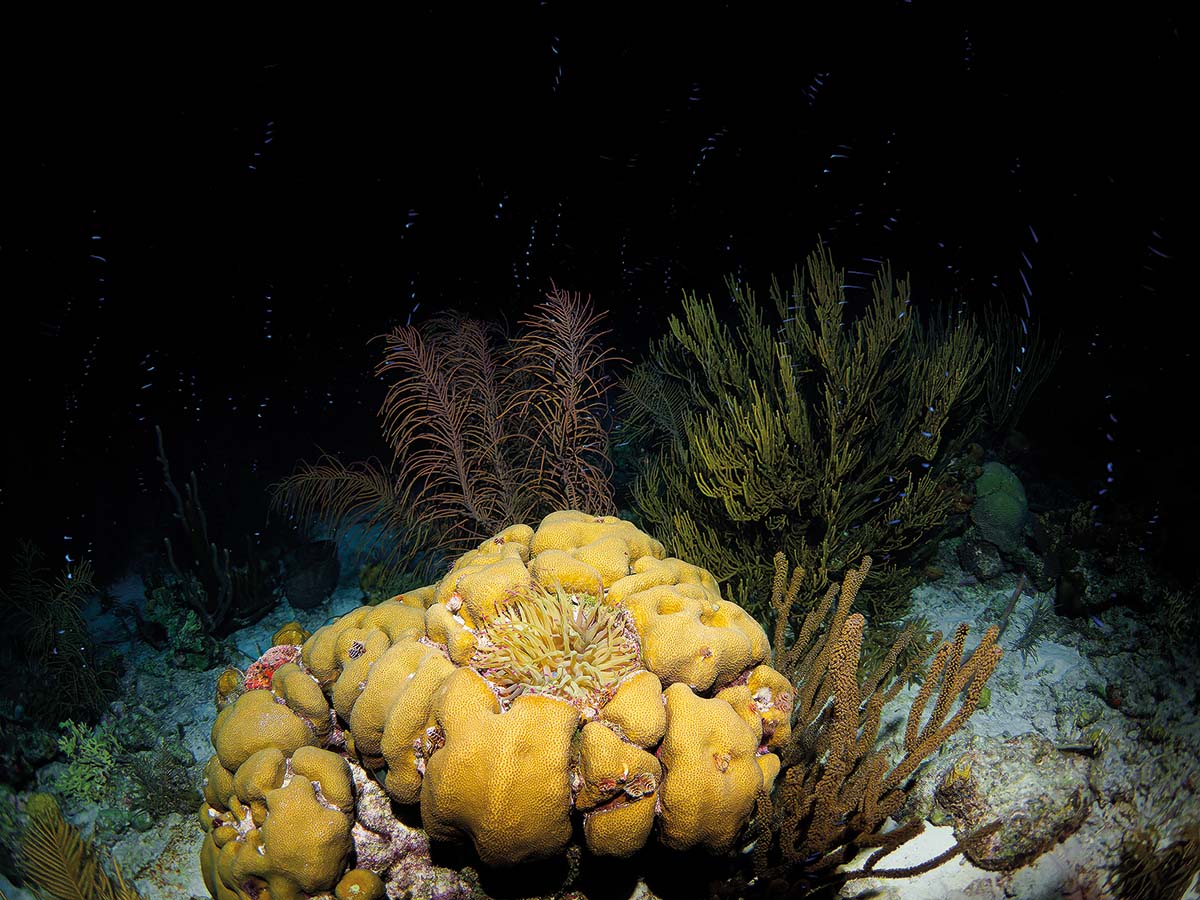

Ostracods, it turns out, do not like anemones, and in choosing to set up in front of a giant anemone on a hard coral bommie, I’d inadvertently selected the one bit of reef that the ostracods initially seemed to be actively avoiding.

Fortunately, I had also made sure to include plenty of soft coral sea plumes (Pseudopterogorgia spp.) in the frame, which normally they seem to favour, and it wasn’t long before the ostracods in front of my camera overcame their initial shyness and joined in with one of the most impressive displays I had ever seen.