As with many things in Japan, this enigmatic country’s rich and exciting scuba diving is a mystery to most people who don’t live there. We asked Martin Voeller, who was born in Japan and now lives in Tokyo, to be our guide…

Okinawa lies in the south of Japan and is technically considered subtropical, as its climate is characterised by hot and humid summers and mild winters. It lies at roughly the same latitude as Hawaii and the Bahamas. This southernmost prefecture of Japan, comprised of more than 150 islands, was a separate kingdom (Ryukyu Kingdom) up until the middle of 19th century when it was annexed by Japan.

Okinawans have their own language, religion, culture and traditions (the region is the home of karate). It was a major battleground during the Second World War, and after the war the islands were occupied by the United States until 1972 when they reverted back to Japan.

In the far south of the region, not too far from Taiwan, is Ishigaki Island. Local scuba magazines regularly rate Ishigaki as offering the best diving in Japan, and one of the reasons is the number of manta cleaning station dive sites there – the most famous is Manta Scramble, in Kabira Bay. The bay is usually well protected from the typhoons which can creep up from the Pacific during the hot summer months. A cleaning station sits on top of a reef with excellent visibility of more than 30m and is quite shallow – about six metres in depth. Therefore, snorkellers can hover over the cleaning station from above. During the breeding season in late autumn, more than a dozen mantas can be seen queuing up for a pedicure.

However, not everything is as wonderful in the rest of Ishigaki. Although this island and its surrounding waters once boasted some of the richest and largest coral reefs in Asia, the recent rising water temperatures have wiped out close to 70 per cent of its corals. Most of this occurred in one season in 2016, when a strong El Niño hit the area. It is devastating to see today’s graveyard of bleached and dead corals. Conservation efforts are underway, slowly, and I have witnessed about 20 per cent of the bleached corals to be recovering. It is heartening to see small buds regenerating on top of bleached corals. Yet, our generation will never again see the likes of the large table corals that once graced the area and have died in recent years.

Miyako Island, slightly further north, is made of coral limestone, and after being eroded by sea, rain, waves and currents over millennia, is riddled with caverns and caves underwater. Visibility is excellent, and sunbeams penetrating through the caverns form underwater cathedrals, much like those seen in the Red Sea. Miyako Island was also surrounded by healthy coral reefs, which have now succumbed to bleaching. Around Yabiji the hard corals were colourful – ranging from yellow to orange to purple – and when the tide was low, they stuck out above the ocean surface. My last visit to the island was in 2016, when the El Niño hit. It was mid-July and the water was warm – too warm! My dive computer displayed 35ºC underwater. Corals start expelling zooxanthellae when the temperature hits 32ºC. This was the first time I felt uncomfortably warm while underwater, and the ocean temperatures rose even further in August of that year. The coral damage was extensive.

Aguni Island lies a 90-minute speedboat trip north-west of Okinawa main island and has recently started attracting divers to witness the impressive schools of bigeye trevally which gather in May and June each year. Here, the reefs are still pristine. The schools, locally known as tornadoes, are so large that it can be a struggle to fit all the fish into the camera frame. It is mesmerising once you are inside the swirling balls of fish – you feel as if you are in a washing machine, with the jacks moving around you in perfect synchronisation. I accidentally ended up on the rear end of the ball once, and found myself swimming among a suspicious-looking cloud of red things which were individually thin and were countless: they turned out to be jack faeces!

Okinawa has long been popular with tourist divers and many shops have English-speaking staff, so it should be straightforward for overseas visitors to book diving in the region. There are also plenty of other islands with excellent diving to explore in the region.

The wild north

Hokkaido is the most northerly of the four main islands of Japan. I was born and spent the first eight years of my life there. Diving in the cold winters reminds me of my childhood, when I played almost every day in the snow. After it hosted the 1972 Winter Olympics, Hokkaido became popular among visitors from China, Southeast Asia and Australia coming to enjoy winter sports with the island’s glorious powder snow. When travelling through major cities such as Sapporo or Otaru to reach my diving base, I often get confused as to what country I am in due to the number of foreigners and the different languages I hear in the streets. This changes, however, once I reach my destination, which is far away from ‘civilisation’.

Diving in Hokkaido is not well known, even among the Japanese. The island is large – it accounts for 20 per cent of the nation’s landmass – and there are numerous spots along the coastline for people to dive. On the eastern end is Rausu, where avid cold-water divers go for ice diving. However, I head for the western side called Shakotan, where the winter coastline of snow-covered gorges is picturesque, with groups of Steller sea lions lazing around on the rocks.

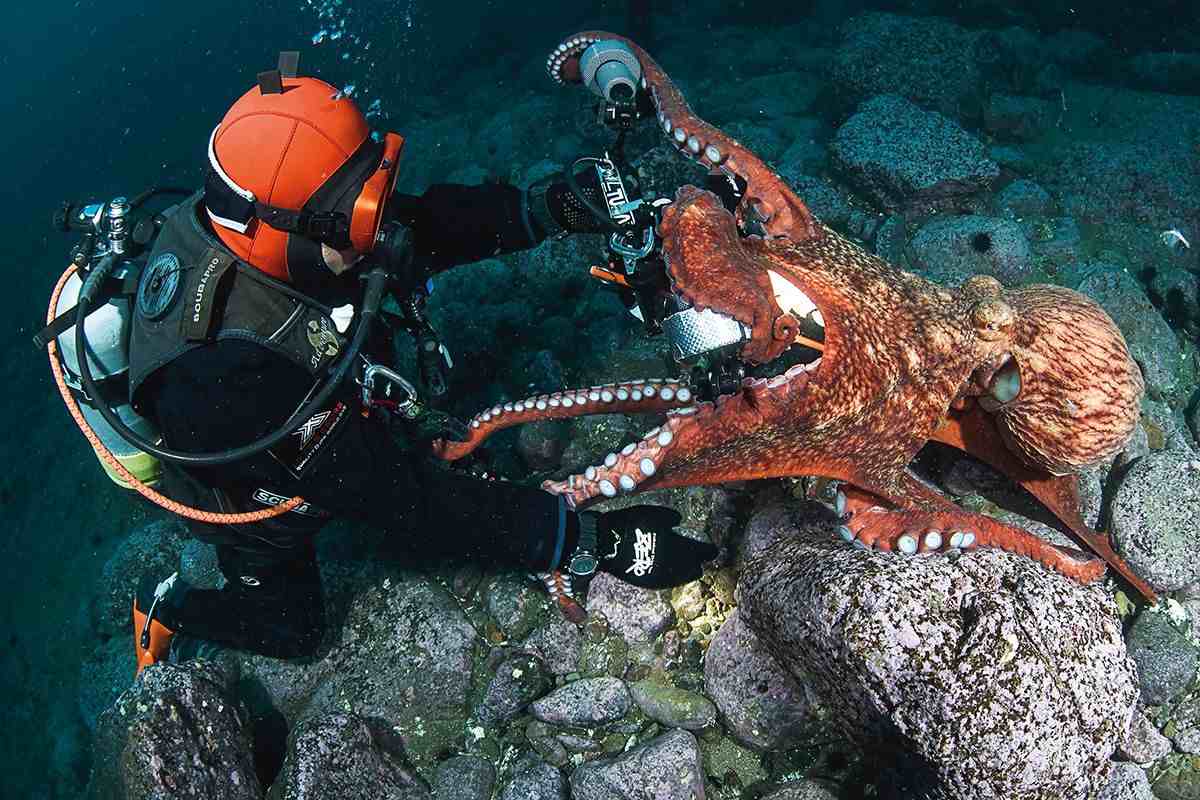

You can observe many links in the food chain while winter diving in Hokkaido. Towards the bottom of the chain are lumpfish and Okhotsk atka mackerel that can be seen carefully protecting their eggs during the cold winter months. These fish are predated upon by the North Pacific giant octopus that hide under rugged rocks and await the perfect moment to pounce.

The Steller sea lions feast on both the mackerel and the octopus, and in turn become prey to orcas and sometimes even humans.

However, you must be prepared to dive in harsh conditions: well below freezing on land; between 4 and 8 degrees Celsius underwater depending on the month; heavy and incessant snow; and choppy waves on the ocean surface. Although it is dark underwater due to the snow and clouds, the visibility is often beyond 20m. There are only two dive shops in the whole of Hokkaido that offer boat diving in the winter. They will take the boat out as long as the waves are below three metres in height, which is about 60 per cent of the time!

The Steller sea lions breed and give birth to pups in the Kuril Islands of Russia during the summer, and migrate to Hokkaido during the winter to feed. They love both the mackerel and the octopus. and they are very curious about humans underwater often coming extremely close. They are the largest of the eared seals and the largest sea lion. Adult Stellers are about two to three metres in length, and male bulls can be as heavy as a tonne. It is quite dark underwater, and the sudden appearance of a fast-moving, massive shadow can be alarming. But as they elegantly dance and curiously stick their googly-eyed faces in front of you, you are quickly entranced and even forget about how freezing it is underwater, and focus on the precious moment you are having with these magnificent marine mammals. These encounters can last anywhere from seconds to minutes.

If you look closely at the Steller sea lions, you will notice that they are often branded on the side of their bodies. When the pups are born in Russia, they are marked with their place of birth and the population count for conservation purposes. Stellers are on the IUCN Red List of near-threatened species. There is an ongoing conflict between the Stellers and local fishermen. The Stellers ransack the fishermen’s nets and steal their fish. The fishermen are allowed to hunt up to 200 Stellers a year. But this number only includes those brought to land – most of which are then sold for human consumption (sea lion curry is a local delicacy). Stellers that are killed and dumped at sea are not counted. Hence, the number of Stellers killed each year significantly surpasses the quota of 200.

Another photogenic sea creature is the North Pacific giant octopus. It is another big beast. Adults generally weigh between 20 to 30 kg and have arm spans of between two and three metres. The juvenile octopuses are generally timid and will run away from divers, but the adults are the exact opposite. I was once photographing a small lumpfish when I was attacked from the side by an adult giant octopus. It had its arms fully spread out and lunged immediately towards my camera. They seem to think that cameras with long strobe arms are enemies, and love to wrap themselves around them and try to pull them away from you. Thankfully, they do eventually let go, but you must ensure that your mask or your regulator is not stripped away – they have extremely powerful suction cups on their arms.

Macro mecca

I live in Tokyo, which is located more or less in the centre of Japan. For divers who want to get away from the city over the weekend, it is common to head for either Chiba – a neighbouring prefecture that lies east of Tokyo, or to Izu, which is a peninsula located west of the city. Both are accessible by car in a couple of hours, depending on traffic. Chiba is famous for the dive site in Ito where hundreds of banded houndsharks and hordes of red stingrays gather to be fed. Fishermen supply the food to the local dive centre in order to keep the sharks away from their nets. Read the full story about these remarkable gatherings in DIVE’s Winter 2018/19 edition.

Izu, a large mountainous peninsula, has the largest number of dive sites on the main island of Honshu. The peninsula is the result of the Philippine Sea Plate colliding with the Okhotsk Plate at the Nankai Trough. There is a 70 to 80 per cent probability that an enormous earthquake, with a magnitude of 8 to 9, will strike along the Nankai Trough in the next 30 years. When the last major earthquake of magnitude 9.0 struck Japan, strange and rare deep-sea creatures appeared near the ocean surface in Izu, including an Atlantic footballfish, or the man gobbler, (Himantolophus groenlandicus) which is usually only found at sea depths of 200-800m. Last December, when there was a spate of volcanic activity around Indonesia, the banded houndsharks in Ito disappeared days before the volcanoes erupted. Only after the eruptions had stopped did they return.

Water temperatures around Izu generally range between the mid to upper 20 degrees Celsius during the summer and dip down to the low teens during the winter. What makes this area special is the Kuroshio Current – or the Black Tide, that starts in the Philippines and flows northeastward past Japan, where it merges with the easterly drift of the North Pacific current. It is similar to the Gulf Stream in the Atlantic Ocean, whereby warm and tropical currents flow to the polar region. The Black Tide brings warmer sea temperatures and interesting marine life to the area. The beaches on the peninsula are often of dark sand (volcanic ash) dotted with rugged rocks. Visibility is generally not great during the summer months – about 10 to 20m at best – but in winter months it can extend beyond 20m. The volcanic rock formations create steep walls and drop-offs interspersed with healthy reefs where lots of marine life thrives.

A dive site called Osezaki in West Izu is one of my favourites. It is the macro mecca of the Kanto region of Honshu. Year-round you can find nudibranchs, gobies, seahorses, frogfish, anthias, squid, moray eel, and shrimps, to name just a few. If you book a guided dive with one of the local dive shops, you will be shown where the best critters are located. A bizarre array of artefacts has been scattered on the ocean floor – wheelchairs, shrines, statues, bathtubs, car tyres and much more. When I first saw them, as an open-water student many moons ago, I was shocked, thinking that people were polluting the ocean. However, I soon realised that they are a safe home to an amazing plethora of macro life. Although Izu is not known to have many hard corals, vivid and large soft corals with colours ranging from yellow to red to purple can be seen at most dive sites.

The ugly, monster-like monkfish (Lophius litulon) is a deep-sea dweller, but during the winter months comes to the shallower depths of Osezaki. These metre-long ambush predators are perfectly camouflaged on the sandy sea, but you can often spot them by their enormous gaping mouths. Another bottom dweller, and ambush predator that is commonly seen during the winter months is the Japanese angelshark (Squatina japonica). Shaped like an angel, it grows to more than 1.5m long. In spring, mola molas are sometimes spotted on the local cleaning stations.