A study covering years of recorded whale shark sightings has found that the world’s largest fish has an extraordinary ability to heal after being seriously injured.

During trips to Djibouti and Seychelles, Southampton University PhD student and lead author of the study, Freya Womersley, of the UK’s Marine Biological Association, noticed that many of the photographs used to identify individual whale sharks depicted animals with injuries that could not be seen on their bodies at subsequent sightings.

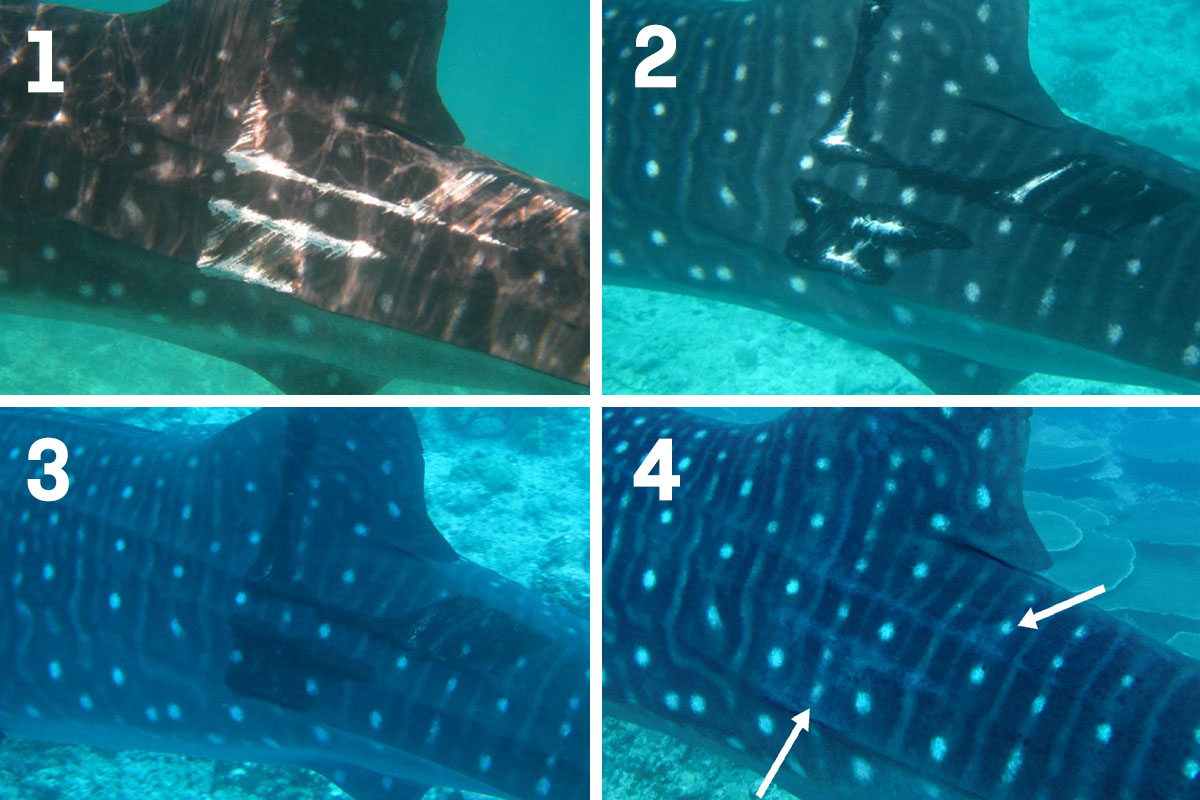

‘Whale sharks can be identified using their spot markings,’ said Womersely, ‘and we were encountering seemingly unblemished sharks that were matching IDs with individuals that had previously been seen with very serious wounds.’

Teaming up with James Hancock of the Maldives Whale Shark Research Programme and David Rowat of the Marine Conservation Society Seychelles, Womersly began searching through more than ten years of ID photographs to look for evidence of how rapidly the sharks were able to heal. The Maldives in particular was important, as it is an area where whale sharks are commonly encountered and, as a popular tourist destination, are all too often injured by fast-moving boats.

‘The Maldives represents one of the global aggregation sites where whale shark tourism urgently needs stricter regulations,’ said Womersely. ‘We wanted to produce a study that both highlighted the healing capabilities of this species for the first time, and also shed light on the issue of human-induced injuries, to provide the evidence needed to support stricter regulations around tourism sites.’

Trawling through thousands of whale shark ID shots, the team discovered that in some cases, whale sharks were able to heal from serious wounds in a matter of weeks or months. Even more astonishingly, one shark observed in the study appeared to regrow almost entirely an amputated section of its

upper dorsal fin over a period of five years, the first reported case of an elasmobranch regrowing part of an appendage.

Anecdotal reports of elasmobranchs’ ability to heal are widespread, but barring a handful of studies into reef sharks and manta rays, there has been little research into the phenomenon. ‘We need more histological studies that highlight the cellular processes behind tissues reforming,’ said Womersely, ‘but these require controlled laboratory assessments, which is difficult for large animals.’

Related articles

- Orca attacking adult whale shark to eat its liver

- Whale shark reproductive ultrasound study published

- International shipping threat to endangered whale sharks

- St Helena’s whale shark mating secret

- Whale shark mating behaviour photographed at Ningaloo

One particularly significant finding is that the whale sharks’ spot patterns are more than just external skin colouring. ‘We were really excited to discover that the whale sharks’ unique and complex spot markings reformed in the exact location where they were before the injury,’ said Womersely. ‘This is a new finding for whale sharks and, to my knowledge, there is very little literature out there on this capability in other animals.’

The reappearance of the markings is thought to be a product of the ‘dermal denticles’ – scales with an enamel-like coating with a structure similar to human teeth – that make up the outer layer of a shark’s skin. The scales reform over the injury site, along with the pigmentation they possessed before being damaged. ‘This observation certainly suggests that these markings are important for whale sharks,’ said Womersely, ‘and I hope studies such as this one will promote more detailed research into these areas for whale sharks and other elasmobranchs with unique patterns.’

Rapid healing and the partial regeneration of severed limbs are not unique to whale sharks, as they are well-known abilities found in newts, lizards and some bony fish – all of which are much easier to study than whale sharks but which also come from ‘a very different branch on the evolutionary tree.’ Biotechnological research into replicating the regenerative process for the treatment of severe wounds in humans is already underway, and although this particular study does not form part of that research, it does add another string to the scientific bow.

‘What I hope that it can do,’ says Womersely, ‘is to open the door for future work that can target some of these novel scientific questions. This finding provides a great incentive for more directed histological studies of shark fins, to determine the conditions required for wound healing and regeneration, which could potentially help inform efforts of regenerative medicine.’

While the scientific elements are undoubtedly fascinating, the study does highlight once more the devastating impact that humans have on sharks. With a recent report suggesting that 71 per cent of pelagic shark populations have been ravaged in the past 50 years, the new research into whale shark healing reveals the terrible consequences of unregulated megafauna tourism.

‘Whale sharks have been experiencing population declines globally from a variety of threats as a result of human activity,’ said Womersely. ‘It is imperative that we minimise human impacts on whale sharks, and protect the species where it is most vulnerable, especially where human-shark interactions are high.

‘There is still a very long way to go in understanding healing in whale sharks,’ she adds, ‘but our team hope that baseline studies such as this one can provide crucial evidence for decision-makers that can be used to safeguard the future of all whale sharks.’

‘Wound-healing capabilities of whale sharks and implications for conservation management’ by Freya Womersley, James Hancock, Cameron T Perry, David Rowat is published in Conservation Physiology