DIVE talks to Michael Miles, a 71-year-old Swiss diver who spent some 36 hours trapped in his cabin in the capsized Egyptian liveaboard, Sea Story

The Dive Pro Liveaboard-owned Sea Story, carrying 46 passengers and crew, capsized near Sha’ab Sataya between 2 am and 3 am on 25 November 2024. Only 35 of the people on board survived.

By daybreak that morning, 28 of the survivors found themselves drifting inside the liveaboard’s two ill-equipped liferafts (as detailed in part 1 and part 2 of this series), but at least 11 people remained trapped inside. There may have been more – but we shall never know the fate of the seven divers whose bodies have, to date, not been found.

Some early reports suggested Sea Story ‘sank quickly’, but although she took on water rapidly causing her starboard side to be mostly submerged, she eventually came to rest at an inverted angle where she remained, floating at the surface and relatively stable for the better part of two days.

Two German men managed to escape their cabin and were picked up by a rescue helicopter some seven hours after Sea Story capsized, but despite the arrival of an Egyptian military vessel at the scene of the incident, it would be another 27 hours before the five remaining survivors would reach the surface.

The Sea Story series:

- Part 1: Sea Story liveaboard survivor tells her story

- Sea Story survivors speak out – Part 2: The Rescue

- Sea Story survivors speak out – Part 4: The ‘interrogation’

Michael’s Story – ‘That boat is too high’

Like most of the other divers on board the ill-fated trip, Michael Miles, a 71-year-old retired architect from Lausanne in Switzerland, had booked a Deep South itinerary on board Tillis, one of Dive Pro Liveaboard’s other vessels.

Like the other divers, he was disappointed in the change of itinerary, and was not impressed by the much larger and – ostensibly – much more well-appointed boat on which he was about to embark.

‘Well, even before I got on it, I was walking with my wife along the port from the hotel, and I said to her, “How crazy they are to build those ships so high”,’ he told me when we spoke, ‘because my experience on other ships is that they were not very stable.

‘The first [liveaboard] I had been on had only two floors, then the third one had three floors, and this one had four. And for me, it was just very bad, to have boats so high.’

Adding to the disappointment was the lack of welcome on arrival, as nobody seemed to take any time to greet the divers. He had also booked a smaller boat with what he thought would be smaller dive groups, to now find himself on a much larger boat with group sizes of the maximum ten divers per guide allowed by Egyptian regulations.

The divers were asked to sign a safety declaration but Mike refused, telling one of the guides that he hadn’t been given any safety instructions; hadn’t been told where the first aid kit or any other safety equipment was located. The guide told him where they were, but Mike felt he should have been given a tour of the boat and shown in person – as he had been on the three liveaboard trips he had previously taken.

The safety briefing was eventually made the next day – after the guests had already been on board overnight – and most of the survivors agree that it was, in general, well-made and informative. There was no muster drill, however – no tour of the boat – and one item in particular that was missed as a result might have made a huge difference to what happened the next night.

‘The escape route,’ said Mike? ‘Well, he didn’t show it. He said it existed, and I knew what he was talking about, but when came the need to use it – I had no idea how long it would take to get to, and that became a very important lack of information because I had no notion of how long it would take to get out.’

My bed was on the wall…

With the first briefing scheduled for 5.30 am the next morning Mike went to bed at around 9 pm; his cabin-mate – a 69-year-old gentleman with whom he was not previously acquainted – a little later. Unlike some of the other survivors, Mike said he was not bothered by the boat’s movement and slept very well. So well, in fact, he believes he continued to sleep as the vessel rolled over.

‘I was not bothered by the movement of the ship,’ he said, ‘but at one moment I realized that the tilt of the ship was unusual. It didn’t 100 per cent wake me up, but put me in a kind of mode where you’re half awake and aware of what’s going on around you.

‘Shortly after, it turned on the other side, and this time it was much more tilted,’ he said. ‘I should have fallen out of bed but I did not, and the reason I didn’t wake up, and the reason I didn’t fall out of bed, is because the bed went up the wall.’

According to the other survivors, after Sea Story turned on its side, the boat continued sinking towards its starboard side for another 20-30 minutes before reaching a point where it remained stable in the water. Mike, however, said this time felt like 10 seconds.

‘For me, this is where the story becomes strange,’ he said. ‘From the moment when we were at 90 degrees to when we were completely capsized, it felt around 10 seconds, so when I read the stories of the others who say it took 30 minutes, probably the only explanation is that I didn’t wake up completely, and was probably sleeping.

Michael was still lying in his bed, which was now lying on the interior wall of the cabin, closest to the corridor. His cabin-mate also didn’t react immediately, possibly because his bed – which was on the other side of the cabin – had slid against the side of what used to be Michael’s. As the boat continued turning though, both men would get a sharp and serious wake-up call.

‘[My cabin-mate] landed on my mattress, and that really woke me up and brought reality to what was happening.’ said Michael. ‘We tried to find the light switch because it was dark, but I couldn’t find it, and then he said to me: “What you’re looking at is not the wall; the ceiling is the wall and the door is not where you think it is”.

‘We found the switch but the light was not working. We managed to get to the door – and even before we opened it we could see water oozing inside the cabin.

‘We opened the door to evaluate the situation in the corridor, but the corridor was already two-thirds full of water, and this is where we took the option to stay inside the cabin.’

There was no sound and no movement in the corridor when Michael opened the door. His cabin-mate initially wanted to try and get out, but by this time the water was so deep that they would have had to swim underwater to reach an exit.

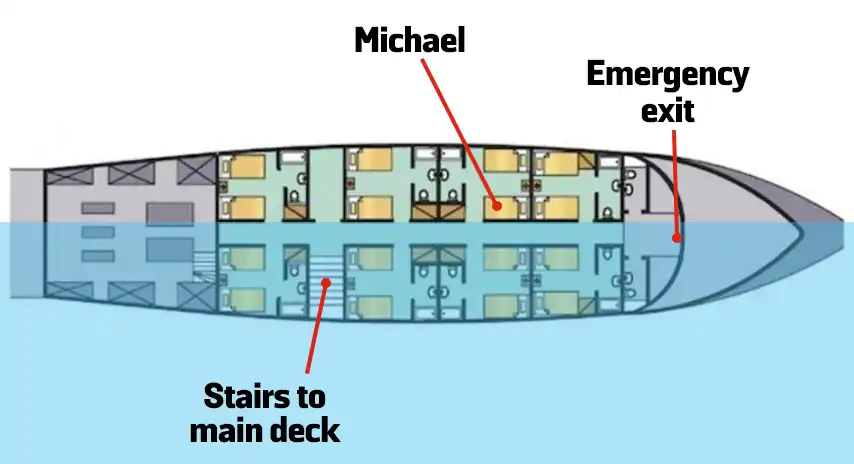

The door to their cabin was almost equidistant between the front and rear of the lower deck sleeping quarters. The stairs to Sea Story‘s upper deck were located on the starboard side of the boat towards the rear of the quarters and completely submerged, and the emergency exit at the front of the sleeping quarters was some 10m away – and also underwater.

Although he had been told where the emergency exit was during the briefing, having not been given a tour of the boat he did not know what he would find on the other side, and no guarantee there would be space and air to surface into.

‘I pointed out to [my cabin-mate] that to be able to get out, he would have to dive under the water, and would he be able to swim underneath the water for that long? And I said if you don’t manage to do it, you’ll die.

‘I said to him that I’m feeling that the boat is stable and it won’t sink, so for the moment, we can stay inside. And if ever we realize that the boat is not stable enough, we can always try a desperate move out.

‘So this was the option. So we closed the door because a lot of broken things in the water were coming inside, and we didn’t want to have them in our cabin.’

Trapped

The silence was broken by the sound of somebody banging on a wall and a woman’s voice shouting for help – likely the Belgian couple Lucianna Galetta and Christophe Lemmens, who were trapped in the engine room with one of the Egyptian dive guides, Youssef al-Faramawy.

The interior of the cabin Michael and his cabin-mate were trapped inside was gradually filling with water. At first, the two men were able to use one of the mattresses to rest on, but it too began to sink. They had a dive torch and a light from Michael’s camera which they used sparingly to analyse their situation.

The water level in the cabin, now angled at 45°, rose up to just below their armpits. Wearing their lifejackets, the two men stood as high on the walls as possible, where the water was only waist-deep, to try and stay warm. Michael spent the first few hours organising what he could, and directing his cabin-mate in what they needed to do in preparing to be rescued.

‘I told him, “You know, you have to prepare yourself to be saved. You have to get dressed, so go in your suitcase and put on what you have. If you have socks, put them on because you lose temperature through your feet.”

‘I had everything in the cupboard, but when I found some things floating I put them on.’

Apart from the banging and shouting from inside the capsized boat, they did not hear any noise from the outside, including the RIB that had earlier approached the boat to pick up Natalia, the Spanish dive guide who had swum back to Sea Story to try and find help while Sarah Martin and a small group of survivors clung onto each other as they drifted away in the darkness.

A glimmer of hope

Six or seven hours after Sea Story capsized, Michael heard the approach of the rescue helicopter.

‘We were happy about it that,’ he tells me, ‘because we at least were certain that somebody had found where we were, and we were certain that the signal had been sent and that somebody knew that we were.’

The helicopter would spend around 10 minutes in the area as it collected Mathias and Danilo, the two German divers who had managed to escape their cabin on the middle deck after previously being trapped inside.

Michael kept his eye on the water level inside his cabin and the behaviour of the boat in order to decide whether or not to make a break for it while the helicopter was nearby, but judged the vessel stable and the risk of swimming the distance underwater too great.

Instead, he grabbed the bedside cabinet – which should have been secured but in this case, fortunately, wasn’t – and asked his cabin mate to hold it in position while he tried to reach the porthole above them to signal their presence.

The waves, he said, were not very strong but one struck the boat with enough force to cause him to fall from his precarious platform and injure his chin. His second attempt was successful and he managed to open the porthole and, using a whistle from one of the lifejackets in the room, whistled as hard and as loudly and for as long as he could.

Eventually, the helicopter left, and so Michael closed up the porthole and went back to waiting.

No, I’m not afraid.

‘After the helicopter left, I imagined it would be perfectly normal that nothing happened for the next three hours,’ Michael said. ‘I thought: they’ll give the signal to something bigger to come over, and it will probably take one hour to prepare and another two hours to come over.’

But nobody came.

By four o’clock in the afternoon, the light was fading and the two men realised that they would have to prepare themselves to spend the night, cold and trapped but not quite alone as they communicated, after a fashion, with the other divers banging on the walls.

Michael is clearly a very practical man – when I asked him how he felt at this point he said: ‘Well, not too happy about it.’

‘But I was in survival mode,’ he continued, ‘so I just took things as they were; didn’t take it too badly; I just said, well we have to spend the night, so we will spend the night.’

Michael’s cabin mate was less stoic, and becoming anxious.

‘He asked me if I was afraid,’ said Michael, ‘and I said “No. I’m not afraid”. When he asked me why I said “Because it won’t help to be afraid”.’

Instead, Michael tried to lighten the mood by preparing once more for the rescue that he knew was still a minimum of 12 hours away.

‘I tried to cheer him up; I said to him, “When we get saved, we will need to have identity cards, credit cards and cash. So I’m going to go in my suitcase.”

‘The only thing I had inside was my wallet, and I grabbed it, showed it to him, and I said, “Now look, I’m going to put my wallet in my pocket. And if I were you, I would do the same, put your wallet inside, because when we’ll be saved, you’ll need it!”

‘And then he said to me, “I think I’ll start to think like you”, and then he was feeling better.’

Michael says that the night passed quickly, probably due to his body being in ‘survival mode’, not feeling any pain despite repeatedly banging himself on obstacles in the cabin.

All through this time, Sea Story was shifting in the water. At some points the movement of the boat would bring the porthole within easy reach; at others, the cabin door would be completely submerged and the porthole inaccessible without climbing.

I asked Michael if he thought the conditions were bad enough to have prevented a rescue operation the day before.

‘No,’ he said, emphatically. ‘Inside the cabin, we were feeling what was going out outside. So inside the cabin, we are having small movements of water, and from time to time we had a bigger one.

‘That is the also the reason why I stayed inside – the conditions outside were such that the boat was not suffering from the sea, because if I noticed that the waves were banging on it and making the whole thing move, I would not have stayed inside. I stayed because I felt safe inside.’

As dawn broke the next morning, now some 27 hours after Sea Story capsized, Michael began to feel dizzy with the smell of diesel that had leaked out of the boat’s engines and fuel tanks and had surfaced inside their cabin.

Unfortunately, the vessel had moved and the porthole had become impossible to reach, but fumes and a dwindling supply of oxygen in the small space forced their hand.

Michael found a piece of wood and wedged it into a crack in the wooden wall that expanded and contracted as the boat shifted in the swell. Supported by his cabin mate, he climbed on it and wedged himself by the shoulders in the opening where the porthole – which needed two hands to open – was located, and the room rapidly filled with fresh air.

At the same time, his cabin mate handed him a pair of trousers from which Michael placed a leg outside to signal their presence, while whistling once more as loudly as he could.

Bubbles and lights

The rescue, when it came, was unexpected.

‘That was a lucky time,’ said Michael, ‘because most of the time we were looking at the porthole, but at one moment I was floating and looking at the wall and my eye caught a flash of lights underneath the water.

‘I had the feeling that my brain was starting to create something that did not exist, but I looked at the door that was under the water and saw another flash of lights, and I realized that it was opening slightly, but could not be opened more because the mattress was lying on it, and the mattress was full of water, so it was very heavy.

‘I pushed the mattress to the side and put my two feet on each side of the door, grabbed a handle and pulled it open, and then I saw bubbles and more lights, and I turned around to my cabin-mate I said, “Now we are saved. They have bubbles”.

‘It meant that somebody was there with a bottle of air,’ said Michael, ‘and for me, that was what I was expecting from the beginning, somebody coming inside with diving equipment, and just taking us out.

The rescue diver – not a military diver but a regular dive instructor from Marsa Alam named Khattab al-Faramawy, the uncle of the trapped Egyptian dive guide – did not have a spare mask, but he put Michael on his alternate air source to swim them out.

‘I said to my cabin-mate: “Get yourself ready, he’ll come back to fetch you” and then we left.

‘It took around two minutes to get out,’ said Michael. ‘We went out through the security escape. We went in the cabin. We went down some stairs. We went through a tunnel and then we arrived in a room where there was a bright blue light, and the blue light is the colour of the sea with a big opening that we got through.

‘He pulled me away from the boat, and we went up. When we arrived at the surface, they had a Zodiac turning with two people on it. One of them threw me a rope.

‘The diver went back to fetch my cabin-mate, and he said to me, “Don’t stay in the water. There are sharks hunting”.’

The rescue that nearly never was

Michael said he first saw the lights of his rescuer at around 2 pm in the afternoon, yet the rescue divers had been on site since 10 am. Other survivors have detailed the arrival of an Egyptian Navy boat the day before – yet none of the people trapped inside were aware of its presence.

‘I think the military ship didn’t make any attempt,’ said Michael. ‘They didn’t even come to look at the porthole. They didn’t even try to see. Didn’t even try to signal their presence.’

Far from the coordinated search and rescue operation that was reported in the media, It appears – at least according to the survivors with whom we’ve spoken – that the divers who eventually performed the rescue were never sent in to look for survivors, but to recover their bodies.

‘From what I understand,’ said Michael, ‘they started the operation at ten o’clock in the morning, and then they gathered the corpses, and then found Youssef and Lucianna and Christophe. Then [the rescue divers] asked if there were any other people, and they said “Yes, we’re hearing noise.”‘

Four bodies had been removed from the wreck before any of the survivors were found. After the three people trapped in the engine room had been brought to safety, one of the rescue divers became ill and the rescue of Michael and his cabin-mate was paused until a replacement diver could be found.

Despite the heroic efforts of the Egyptian rescue divers, between 10 am and 2 pm when Michael was finally rescued, still, no attempt at contact was made.

‘They sent out three boats to come and rescue people,’ said Michael, referring to the privately owned boats dispatched from Marsa Nakari Resort to search for survivors the day before. ‘And if they managed to send out three boats to rescue people, Why could they not put on diving equipment and come down?

‘The boat (Sea Story) was not moving more on the previous day than on the next day. The Army boat didn’t do anything, they just stayed around and waited.’

Safe at last

Michael and the four other trapped survivors were brought to the military boat – which he noted carried two Zodiacs with tank racks: ‘If they had bottle racks, they could have had bottles,’ he said – but the welcome they received from its crew was warm.

‘They brought us to a place where we took a hot shower for 10 minutes, trying to warm up, and then to another place where they gave me a cup of tea,

‘I was shaking so much that I could not even hold a cup. So somebody helped me to drink it. The Egyptian tea was excellent!

‘They brought us to another place to have a meal, and though I had not eaten now for maybe 44 hours, I found it difficult to eat. It could only eat one-third of what was on the plate. The only thing that went down very easily was an apple they gave me.

‘Each of the sailors that were around gave part of their private clothes, trousers, whatever, to dress us because everything of mine was wet. I left the boat with their clothes, and they were very, very human and pleasant and agreeable about it all.’

Three hours later the remaining survivors – the last to be found alive – were brought to Marsa Alam to be welcomed by a media circus that had descended on the port since the time the first survivors had been brought ashore the previous day.

‘Before arriving to the pier, we noticed they had a huge big gathering of a lot of people and I said, “Oh, they’re going to do a big show to show how much they are doing and how well they are treating us”.

‘Somebody put his camera or telephone in front of me and asked me to give my impressions, and I thought that if I wanted whatever I was saying to be online, I better say something positive.

‘And the only thing positive I said was how we were treated on the Navy ship, to say that I appreciated whatever I have received. Because this was real. I really appreciated what I did receive, and I didn’t speak of what I did not receive.

‘That is how this got online, and my family got informed that I was saved.’

Michael soon found out his ordeal was not over. With the media already in full swing for 24 hours, he and the others were taken to hospital.

‘We didn’t have any choice. We were put in an ambulance and we were taken to a hospital. I would have preferred to go to my hotel and find my wife.

‘It was maybe not a bad thing, because I needed my wounds to be treated and I was dehydrated, but I would say that – in the hospital, I received a minimum of care.

‘I also had the feeling that we were under police surveillance, because when I went around to walk in the corridor, someone who was probably a policeman asked me where I was going and he said I must go back to my room.

‘The next day when I wanted to get out and warm up in the sun because I still was feeling cold, they told me I was not allowed out of the hospital to be in the sun.

‘I had the feeling that we were being surveilled and that they were protecting us in such a way that we did not speak to the Press.’

Having been trapped for more than 36 hours in a capsized boat, Michael was now trapped in an Egyptian hospital, where it became very clear that rescuing his wallet and credit cards the night before was not just a joke.

‘The person responsible for the hospital, he wanted to be paid. My daughter, who wanted to speak to me, called, and he said to her that he won’t pass me over on the phone and that she had to come to the hospital and pay for me to get out, and if she doesn’t pay, I won’t be able to leave the hospital.

‘I asked him “Do you accept credit cards?” and he said yes, so I said, “Go fetch your machine”.

‘And I was so happy to have in my wallet a credit card, wondering if it will work after 36 hours in the water – and it did!’

This article is part of a series following the stories of Sea Story’s survivors and their experiences dealing with their escape, rescue, and the aftermath of the disaster. Read Parts 1, Part 2 and Part 4 here.

Related articles

- Survivors speak of Sea Story liveaboard sinking cover-up

- Divers speak of safety failings on Sea Story sister ship

- Sea Story liveaboard survivors found trapped in cabins

- Divers and crew missing after Red Sea liveaboard Sea Story sinks

- Red Sea liveaboards are being cancelled – here’s why

- Dylan Harrison instructor charged over her death - 9 February 2026

- The waters of Wakatobi are an artists’ muse - 6 February 2026

- Dylan Harrison’s family to sue PADI and NAUI over 12-year-old’s death - 3 February 2026