The second in a series of articles detailing how survivors of the Sea Story liveaboard disaster escaped from the capsized boat to find themselves drifting for hours before being rescued

In the early hours of the morning of 25 November 2024, the Dive Pro Liveaboard-owned Sea Story, carrying 46 passengers and crew, capsized.

Thirty-five people were eventually rescued, 28 of whom – including the captain, nine crew members, two dive guides and sixteen guests – found themselves adrift in Sea Story’s two ill-equipped life rafts.

Sarah Martin, a Lancaster-based doctor, shared her story with DIVE, the first part of which details the build-up to the incident that resulted in the loss of 11 lives.

We’ve since spoken to Hissora Linse Gonzalez, Spanish CEO and co-founder of Madrid-based WeGoWild Family Travel, who was in the cabin opposite Sarah’s.

Sarah and four other survivors spent approximately 1.5 hours in the water before being picked up by a Zodiac and transported to one of Sea Story’s two life rafts. Unknown to her, 15 other people had already been found and were sitting inside the other.

The Sea Story series:

- Part 1: Sea Story liveaboard survivor tells her story

- Sea Story survivors speak out – Part 3: Trapped

- Sea Story survivors speak out – Part 4: The ‘interrogation’

Hissora’s story

Hissora Linse Gonzalez was one of the first passengers to escape from Sea Story’s lower deck. She was sharing a starboard cabin with a friend and was unable to sleep due to the motion of the boat, and things falling out of cupboards that wouldn’t stay closed.

Hissora was awake when the boat suddenly turned 90 degrees onto its starboard side. Disoriented, she and her companion were unable to find their life jackets, and with the door to the cabin now above them, had to pull themselves up into the corridor.

‘The door was in the ceiling now, so we had to jump to be able to come out of the cabin’ said Hissora. ‘We couldn’t find our lifejackets, and we didn’t have any light.

‘I could hear the water right behind me,’ she told me. ‘I didn’t see it but I could hear it coming in through the windows. I remember saying to my friend “get me out, I’m gonna drown”. He went out first and pulled me up through the door because I could not come up myself.’

Fortunately, Hissora’s cabin was located next to the emergency exit that had been mentioned during the boat briefing, and the pair were able to climb their way out of the boat.

‘We came out of the emergency exit and we had to climb two or three decks – we don’t know how many because it was confusing and dark and full of oil and full of things, and the stairs were not useable.’

‘We came out of the hull, and we actually saw the whole boat sideways, and more than half of it was already underwater. And it was going down fast, because you could actually see it sinking.

‘I remember the noise of things breaking, like wood, like slapping. And then from there, we had to jump in the water. But before jumping in the water, we had to jump into a place that was full of metal.

‘I don’t know what part of the boat it was but if you jumped, you would just land on metal. And I was very afraid. I remember I got paralysed then, and I had people behind me, shouting “jump, jump”.

‘My friend [jumped] before me, and from where he was, he saw somebody trying to get the life raft off, trying to break a rope or something, and he was saying, “Don’t jump! Wait – they are trained to get the life raft off”.

‘But it was taking a long time, and I wasn’t jumping. So somebody pushed me.’

Hissora is not certain what happened with the life raft she saw somebody trying to untie, nor who was trying to untie it, but suddenly in the water without a life jacket, she clutched onto a couple of other survivors who did – one of whom also had a phone in her hand, with a light.

‘We were in the water for, I don’t know, maybe 10 minutes, and the Zodiac came because [we] had a light, so they saw us because it was pitch black, and they came to collect us.’ Once on board the Zodiac, Hissora says that the life raft suddenly opened by itself, although it may be that in the darkness she had not seen one of the other survivors pulling on the rope – the painter line – which activates the compressed air cylinder that automatically inflates the life raft.

In a group interview with German dive magazine Taucher.net, the survivor – who had been trying to sleep on the top deck at the time Sea Story capsized – said that she was picked up relatively quickly after being thrown into the water, together with several crew members and other guests.

They found an unopened life raft still in its white plastic housing drifting free of the boat, which opened and began to inflate when she tried pulling on its rope.

Life raft operation failure

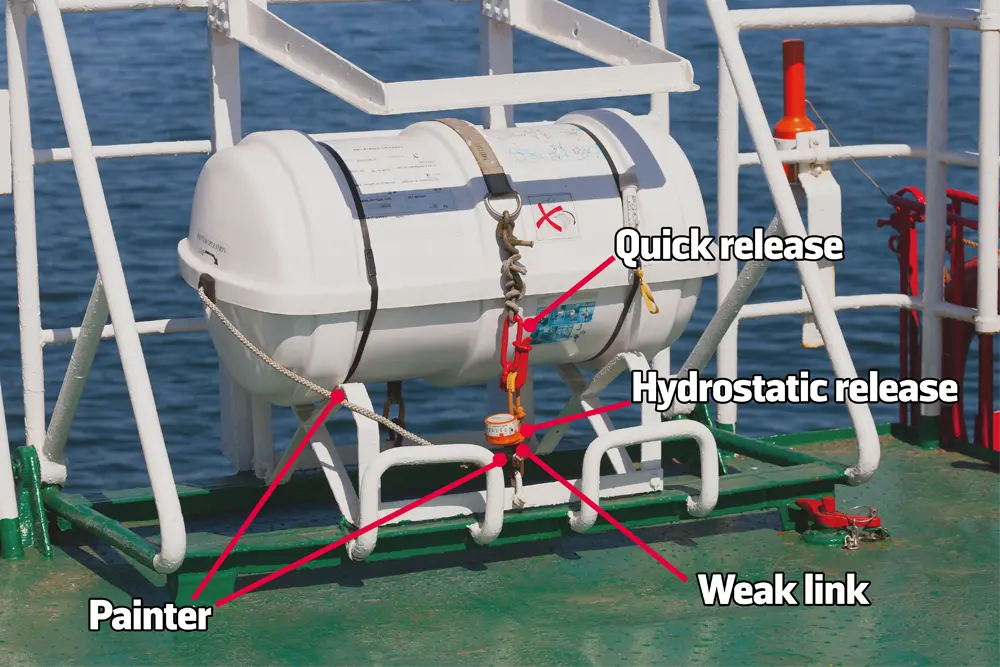

International maritime standards for life rafts stipulate that they should be tethered to the vessel in distress with a ‘painter’, a nautical term for a rope that is typically attached to the bow of a small boat for towing and tying.

When pulled, the painter will operate a cylinder of compressed air to inflate the life raft. Some life rafts are designed to auto-inflate on contact with the water, but this is not a mandatory requirement, and is not always suitable for smaller craft.

Keeping the life raft tethered to the vessel in distress means they are easier for survivors to locate and access in an emergency. Assuming it is safe for the rafts to remain connected to the boat, it also means survivors are kept together and creates a larger target for emergency responders to locate

Most painter systems are equipped with a ‘weak link’ – a clip that will break under strain should the vessel begin to sink, thus preventing it from dragging the life raft down with it.

Boat crews should be trained in how to secure the life raft and how to disconnect the painter if it becomes necessary to do so, or if there is no weak link in the system.

It is not possible to say if Sea Story’s life rafts were improperly secured to begin with, or if they were unwittingly disconnected and thrown overboard by an untrained member of the crew or a panicking passenger. It seems, however, that they were not properly deployed.

It’s also not possible to say if keeping them secured to the capsized boat would have made any difference to the number of people rescued, but it almost certainly would have made the ensuing hours a lot easier for the survivors, and a lot less stressful.

During the boat briefing the day before, the lead dive guide had said that there would be food and water in the life rafts if they were needed – but neither were present.

International Safety Of Life At Sea (SOLAS) requirements state: ‘a food ration totalling not less than 10,000 kJ’ (approximately 2,400 kilocalories) and ‘watertight receptacles containing a total of 1.5 litres of fresh water’ for each person the life raft is permitted to accommodate – 25 people, in this case.

Survivors from both life rafts noted that there were only two or three survival blankets present in each of the rafts, but this may not have been the failure it first appears to be.

SOLAS regulations stipulate that there should be ‘thermal protective aids … sufficient for 10% of the number of persons the life raft is permitted to accommodate’, indicating that the small number of blankets in the rafts was simply down to the life raft’s manufacturer fulfilling that requirement.

The full list of standards for life rafts can be found in the IMO Rules and while many of them were met, important standards concerning the availability of food, water and working lights were not.

It’s also clear that at least one of Sea Story’s life rafts should never have been on board the boat.

A tale of two life rafts

In the information provided by Dr Sarah Martin to DIVE, the survivors refer to the life raft Hissora and the other survivors to be first rescued found themselves on as Life Raft 1. Sarah’s group and the rest of the surviving crew were in Life Raft 2.

A total of 15 people, including two of the Egyptian crew, were in Life Raft 1, which Hissora describes as ‘really old.’

‘It was all discoloured,’ she said. ‘It had two entrances, and you had zippers all around it to be able to close it all – and all the zippers were completely broken.’

It’s actually a requirement under IMO rules that the entrances – one front and one rear – are able to be properly fastened, but that wasn’t the worst safety feature of the life raft to be missing.

‘It was very windy and we were very cold because [the life raft] was broken and water was getting inside,’ said Hissora. ‘It’s like two big rings, one on top of the other, and the lower one was actually broken, so we were sinking slowly.

‘There was a pump, but we didn’t really know how to use it – and we were afraid to, because everything was so old and in bad condition, that if we were to plug it in and inflate it, we didn’t know if it was actually going to let the air come out instead of going in.’

The raft was in such poor condition that boarding handles on its exterior had torn off when survivors had tried to hold onto them.

There were partially complete survival kits in both of the life rafts – flares, smoke bombs, scoops and sponges for bailing were all present, as were a life ring and rope; spare sea anchor, signalling mirror, a fishing kit and a rudimentary first aid kit with all the labels written in Arabic.

Both Sarah and Hissora recall finding a torch without batteries in their respective rafts – Hissora also mentions how her life raft had a bulb-less light fitting dangling from its roof – and, of course, neither contained food and water.

It fell to Sea Story’s paying customers to manage their time in the life rafts. Hissora’s friend, a commercial diver with 25 years’ experience at sea knew how and when to use the smoke bombs and the flares, so took charge of firing two of them when lights were spotted in the distance – although to no immediate avail.

The two crew in the raft did not engage at all. They cannot be faulted for being afraid or not speaking English, but their lack of activity does suggest a lack of training and experience. One of them, however, had a working phone.

‘He was calling and calling and calling and then all of a sudden, he was talking on a phone,’ said Hissora. ‘He was talking for a long time, and then when he put the phone down, we said, “Who were you talking to, emergency?”

‘And he said, “No; management.”’

The next day, the crewmember would change his story and say he phoned ‘emergency’. Hissora says she and others heard him say ‘manager’.

‘I mean, manager is manager,’ she says. ‘Even if you don’t speak English, if you say “manager”, you don’t mean “emergency”.’

Improvisation and a lack of command

Inside Life Raft 2, Sarah and her fellow survivors were going through the same motions as the other – checking for supplies and finding the same problems as Life Raft 1, in that they had no working lights, no food, no water, and a crew that seemed unprepared and unwilling to take action.

They found some used flares and assumed the captain – who was wrapped up ‘to his chin’ in a thermal blanket – had fired them earlier in the night.

There were 13 people in Life Raft 2, three guests, two guides, seven crewmen and the captain – but Sarah says the captain did not assert himself as captain at any point.

It was noticed later that he was clothed in just his underwear, which Sarah and the survivors say ‘raised questions about his state of readiness’ during the incident.

They were told that he had gone to the toilet when the incident happened, begging the questions: why would he leave his post in such unstable conditions, and who exactly was in charge of the boat when it capsized?

One of Sarah’s companions on the life raft – to whom I have spoken but who has asked to remain anonymous – said that when daybreak came, she noticed the crew at the back window of the life raft discussing the sea anchor, a small parachute-shaped device strung from a floating vessel that acts as a brake against drifting and prevents the raft from spinning.

‘They didn’t know what it was and wanted to get rid of it,’ she said. ‘I asked [the Egyptian dive guide] to explain what it is to them so they don’t untie it.

The survivor also details how the damaged and deflating Zodiac they had been picked up with was tethered to the life raft, and said it became necessary to explain to the crew why it was in danger of sinking the life raft, and therefore needed to be untied.

‘It seemed to me that no crew in our life raft knew anything about the life raft or its contents, or what to do in this situation – or if they did, they remained silent.’

Emergency Response – or lack thereof

It’s difficult to ascertain exactly what happened in terms of communication with the authorities, but it does not appear that no distress call was made from Sea Story before she capsized – possibly because she overturned suddenly and rapidly.

The life rafts were not fitted with emergency position indicating radio beacons (EPIRB) nor were there any VHF radios on hand. Several mobile phones had survived and were still functioning, but the survivors were out of range of mobile signals.

One of the guests managed to get enough signal to place an emergency call at 3.07 am local time but unfortunately, the call did not connect. As detailed earlier – one of the crew managed to place a phone call at around 3.30 am, which survivors report he said was to his ‘manager’ and lasted for around 10 minutes.

In a press briefing on 25 November, Egyptian authorities said that they received an alert at around 5.30 am on the morning of the 25 November, between 2.5 and 3.5 hours after Sea Story had capsized.

There is no information as to the source of the alert or why it was not received until some two hours after the crewmember placed his phone call – whether that had been to his manager or, as he later claimed, emergency services.

The first signs of hope

The first sign of hope the survivors on board the life rafts had was the sighting of a container ship in the distance at around 9 am.

Although they were unable to communicate – and barely even see each other over the waves – both groups attempted to signal to the ship, waving their thermal blankets and trying to catch the crew’s attention with their signalling mirrors.

‘This was our first bit of hope and we were thinking, we can’t let this cargo ship not see us,’ said Sarah, ‘but we know we’re so small in the water and the waves, so we needed to get something up high.

‘We took our blankets, attached them to rope, and managed to fly them like kites. We also had a paddle, just waving whatever we could trying to get their attention.

‘We used the mirror – and it was a massive cargo ship and really far away, but then it seemed to just stop and turn and we wondered if they’d seen us.’

Although nobody knows exactly what role the cargo ship played in the rescue, at around 10 am it was approached by a helicopter, which first hovered near the ship before making its way over to the wreck of Sea Story.

Danilo and Mathias, the two German divers who had been trapped in their cabin when Sea Story capsized, had managed to escape and clamber onto the upturned hull. They were winched to safety by the helicopter’s crew.

‘And then they left,’ said Sarah. ‘And they never came back. Then all of a sudden a speed boat just appeared beside us, with survivors from the other life raft already on board.’

The speedboat was not an Army or Navy rescue vessel but a privately owned RIB, dispatched by the owner of Marsa Nakari dive resort in Marsa Alam. The owner had sent three of his boats out to search for survivors after being alerted to the emergency by a friend.

‘[The speedboat’s pilot] saw the helicopter hovering, so he knew that something was there,’ said Sarah. ‘He assumed it was the wreck, and he just followed the currents from where that location was and managed to find both of the rafts quite quickly.’

The survivors from the life rafts were taken to a nearby liveaboard, Star Jet, which had been chartered by a group of Polish divers who gave them items of clothing and phones to call home, while the crew laid on food and provided access to shower facilities.

‘We spent a few hours on Star Jet, said Sarah, ‘and then they brought us to the harbour. There were a lot of ambulances there and they asked if anybody wanted medical attention – but it was all very much: take a picture, video, shake someone’s hand. It felt like the medical attention was very much for the pictures.’

Trapped belowdecks for another 27 hours

The survivors on the two life rafts, plus the two German men rescued from the outside of the wreck, were rescued at around 11am on the 25 November, eight or nine hours after Sea Story capsized – but there were still eighteen people missing.

The survivors say they spotted a Navy vessel following them while they were on board Star Jet, but say they did not see any other boats or helicopters searching while they were in the area – despite media reports at the time suggesting a major search and rescue operation was underway.

Five more people would eventually be rescued from the boat, but not until the afternoon of the next day.

Belgian couple Lucianna Galetta and Christophe Lemmens had become trapped in Sea Story’s engine room while trying to escape, where they were later joined by Youssef al-Faramawy, one of the Egyptian dive guides.

In an interview with the BBC they recounted how they heard the helicopter on the morning of the day Sea Story capsized, but remained trapped in an air pocket in their cabin for another 27 hours.

They were later told that the Navy boat had followed them for 24 hours, but said that after the helicopter left they did not hear anything further to suggest rescue efforts were ongoing, and no attempt appears to have been made to make contact with those still trapped.

Lucianna and Christophe were found by Youssef’s uncle, Khattab – himself a local dive instructor – who took Youssef out of the wreck before returning to fetch Lucianna and Christophe.

Two other men, Michael Miles from Switzerland – an interview with whom will feature in a forthcoming article – and his cabin-mate, who at this time wishes to remain anonymous, were also rescued by the volunteer divers.

The lack of any sort of effort to reach – or even make contact – with the people trapped belowdecks for an entire day is by itself a grievous failure by the authorities.

Worse is the fact that they were, in the end, rescued by volunteer divers, not military personnel, using regular dive gear from a regular dive shop.

Four bodies were recovered and seven people – including British couple Jenny Cawson and Tarig Sinada – have never been found.

There is no way of knowing how long any of those poor people survived after Sea Story capsized, but still, one has to ask: if action had been taken sooner, or the life rafts had been properly stowed, would some of those 11 souls have been saved?

This article is part of a series following the stories of Sea Story’s survivors and their experiences dealing with their escape, rescue, and the aftermath of the disaster. Read Parts 1, Part 3 and Part 4 here.

Related articles

- Survivors speak of Sea Story liveaboard sinking cover-up

- Divers speak of safety failings on Sea Story sister ship

- Sea Story liveaboard survivors found trapped in cabins

- Divers and crew missing after Red Sea liveaboard Sea Story sinks

- Red Sea liveaboards are being cancelled – here’s why

- Full Circle – a return journey through 25 years of Sharm El Sheikh - 25 February 2026

- Hollis 200LX second stage regulator recall notice - 25 February 2026

- Student diver dies during training dive in Golfo Nuevo, Argentina - 20 February 2026