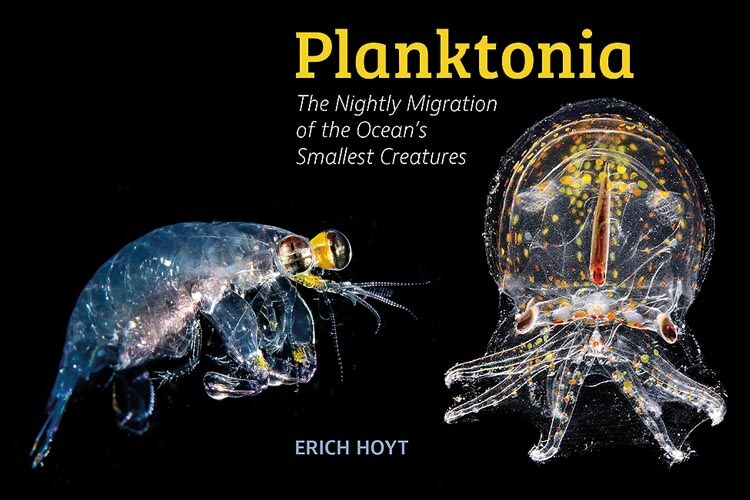

In this extract from his book Planktonia, The Nightly Migration of the Ocean’s Smallest Creatures, Erich Hoyt introduces some of the ocean’s most extraordinary residents

When people hear the word ‘migration’, they often think of humpback whales, Arctic caribou, albatrosses, leatherback sea turtles; animals that move from a feeding area to a breeding area and back, each year.

But the greatest migration on Earth happens twice every night.

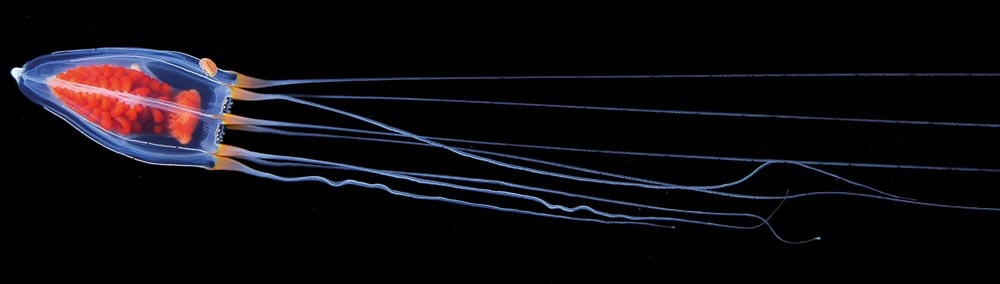

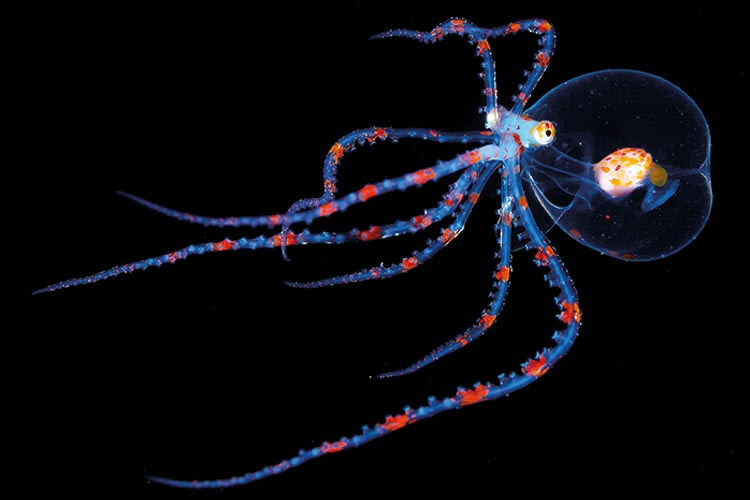

The movement is largely vertical and largely performed by plankton, organisms that drift in the ocean’s currents, and micronekton, the small animals that can actively swim against those currents, accompanied by followers and hangers-on, including predatory fishes, squid, octopus and other species, that have acquired a taste for plankton.

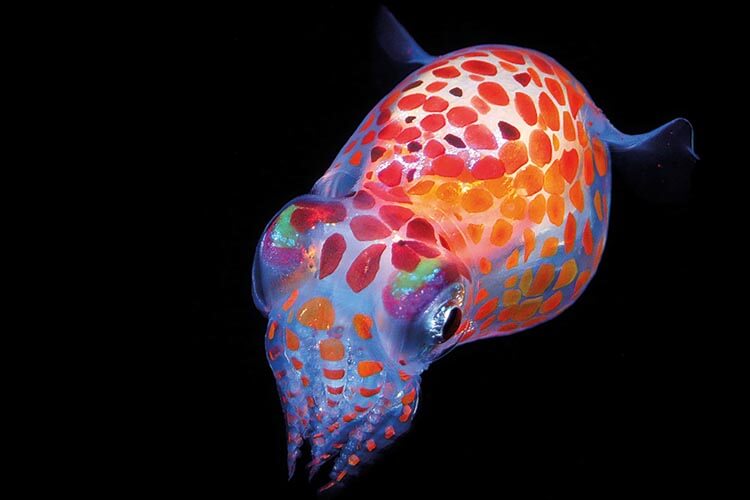

The migration starts deep in the waters of the ocean every evening, at sunset. The nighttime migration is composed of miniature creatures of intricate design, a riot of colour, near-transparency or iridescence, and flashing lights.

As they move, the zooplankton – the animals – nibble on phytoplankton – the tiny plants of the plankton – and other tasty morsels in the water and, eventually, some of the zooplankton on each other.

The feeding ends just before dawn when the plankton retreat to the depths of the ocean to hide during the day until, once again, when evening arrives, they migrate back up the water column.

Swimming up and down the water column must be a heroic feat. To move upwards, some plankton wave their arms like dancers or flap their tails; some use a kind of breaststroke with both limbs; others lurch ahead, often with one limb providing the thrust. It’s amazing how fast you can move if you’re hungry, or trying to avoid being someone else’s midnight feast.

It was in 1817 that French zoologist Georges Cuvier became the first to report this nightly vertical migration of plankton, after witnessing it in a lake. In the late 1800s, Austrian geologist Theodor Fuchs took net samples at various depths of the open ocean to show that planktonic crustaceans were moving from deep to surface waters as night came on. But no one realised how prevalent vertical oceanic migrations were.

During World War II, echo sounders on German U-boats in the North Atlantic found that the bottom of the ocean seemed to be moving up every night! After the war, scientists comparing the mass of plankton and micronekton, such as lanternfishes, that they collected at different depths at night and in the day realised that this was a biological phenomenon happening all over the ocean, from polar to tropical waters.

The global vertical migration of plankton and micronekton was so massive, it was read by the echo sounders as the bottom of the ocean.

Over the past decade, as macro photography combined with diving in the open sea at night has grown in popularity, divers have begun sending their images to scientists and asking them to identify the species.

In some cases, at first, the scientists had only general ideas of what they were looking at. In the case of the fishes, drawing on years of plankton research from net samples, and studying the body shapes, fin placements, numbers of fin elements and muscle segments, the scientists could usually identify family and often genus, but sometimes not the species.

The fin shapes and other fragile parts of the planktonic larvae looked very different to the eventual adult forms. In cases like those, identifications have depended on the ability of the diver to collect an individual so that scientists could match the DNA of the larval plankter to the adult.

With the collection of specimens for genetic analysis, a whole new field has started to open. The photographers in Planktonia — some of them part-time scientists, some working with scientists, some citizen scientists — aim to contribute to that literature, working to identify unknown species and capture their behaviour with a camera.

More from our Winter 23 Magazine:

- Life Changing: Todd Thimios’ stunning Norway orca photography

- Accused: a dive instructor’s wrongful prosecution for manslaughter

- Life Returns – coral reef restoration in Mustique

- Review – A Diver’s Guide to the World