A new study finds that slow genetic mutation means sharks are less susceptible to cancer, but at increased danger from rapid ocean change

Sharks suffer from a very low incidence of cancer but a new study, led by Monash University’s Australian Regenerative Medicine Institute (ARMI), has found that the reasons behind this may also mean they are unable to adapt to rapid environmental change.

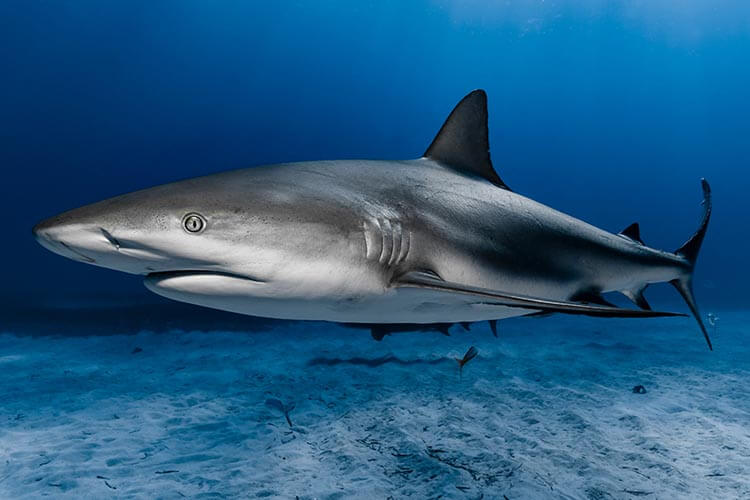

Sharks play a vital role in the ecological health of the oceans; larger sharks are often classed as apex predators in their environments, and there are hundreds of other species that fulfil important ecological niches, from the giant planktivorous whale shark to deep-sea scavengers and the tiny, krill-eating dwarf lantern shark.

Many shark species are increasingly vulnerable to extinction, primarily as a result of overfishing, bycatch, and the notorious trade in fins to make shark fin soup, considered a delicacy and status symbol in the Chinese and South-East Asian markets.

Adding further pressure to shark populations is the promotion of shark cartilage-based supplements as an alternative therapy for cancer in humans. There is, however, no scientific evidence to support the claim, which has had the unfortunate consequence of diverting patients away from effective cancer treatments.

Related articles:

Sharks have the lowest known cancer rates among all vertebrates, but science has for many years been unable to determine the reason why. The new ARMI study, in collaboration with researchers from Germany, Sweden and the United States, proposes that the low incidence of cancer may be a direct result of the discovery that sharks have the lowest known level of genetic mutation between generations of any vertebrate species.

While the low level of mutation between generations may explain why sharks are less likely than other animals to develop cancers, it may also mean that sharks are less likely to be able to adapt to ecological pressures such as dramatic falls in populations through overfishing and habitat loss.

Genetic mutation is a critical component of successful evolution, as genetic variability within a species’ population increases the chance it will be able to adapt to changing environmental conditions.

Sharks are slow to grow and late to reach sexual maturity, with females bearing low numbers of offspring after lengthy periods of gestation. A slow rate of genetic mutation – and therefore evolution – would make sharks ill-equipped to deal with rapid changes caused by unsustainable fishing and habitat loss.

The scientists chose the epaulette shark (Hemiscyllium ocellatum) as the basis for their study. Epaulette sharks are able to travel up to 30m on land by ‘walking’ on their fins and are able to survive up to two hours without oxygen, making them an ideal candidate for laboratory study and, consequently, one of the most comprehensively genetically sequenced sharks so far known to science.

The team searched for genetic variations between two parent sharks and their nine offspring, leading to the result that the sharks exhibited the lowest mutation rate among vertebrate species so far known to science.

‘The mutation rate is a crucial parameter for many calculations and predictive modelling in the fields of ecology and evolution, genetics and genomics,’ said joint first author of the study and ARMI research fellow, Dr Frank Tulenko ‘The rate of mutation provides an indication of a species’ ability to generate diversity, with a low rate of intergenerational mutations indicative of a reduced ability to respond to a sudden drop in population numbers.’

As many as 100 million sharks are taken each year, with some estimates suggesting as many as 73 million are taken for their fins alone. Habitat loss of both sharks and their prey has also had a dramatic effect on shark populations, and changing ocean temperatures can greatly affect their distribution.

‘We know that sharks are particularly sensitive to unsustainable fishing practices and rapid changes in habitats,’ said ARMI Director of Research and study co-author, Professor Peter Currie.

‘As sharks play fundamental roles in a diverse range of marine ecosystems, it is critical that we support conservation efforts to preserve the genetic variation within shark populations and to protect shark species more broadly.’

The study ‘Low mutation rate in epaulette sharks is consistent with a slow rate of evolution in sharks’ by Ashley T Sendell-Price, Frank J Tulenko et al is published in the online journal Nature Communications