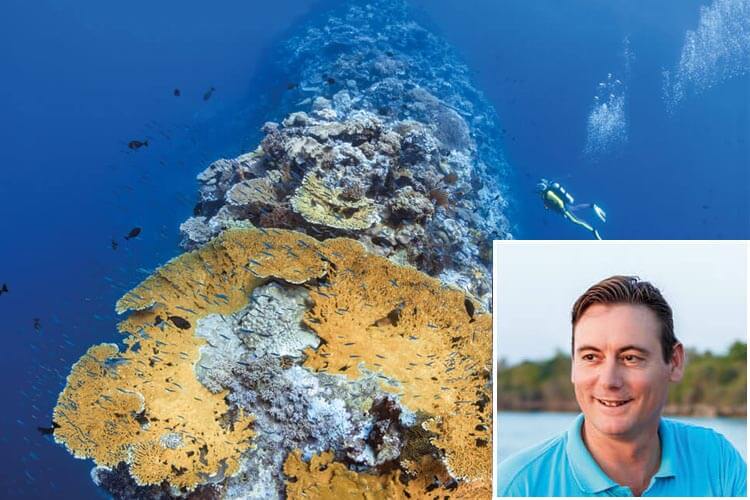

Mark ‘Crowley’ Russell visits Wakatobi and talks to its founder, Lorenz Mäder, about the business of conservation, and the hard grind of making sustainable tourism work

‘There’s nothing bad about money,’ says Lorenz Mäder, Swiss founder of Wakatobi Resort in Southeast Sulawesi, ‘as long as you make good use of it.’

And in the past 24 years, he has made extremely good use of it, building up a world-class dive resort which has used its financial strength to transform the health of its surrounding reefs and marine life. Soft-spoken, but with a no-nonsense demeanour, Lorenz takes a forthright and outspoken line on how conservation works in practice.

Since it first opened in 1995, Wakatobi has become a model for sustainable eco-tourism, although ‘sustainable’ is perhaps not quite sufficient to describe the impact that the resort has had on the local coral reefs. They haven’t only been ‘sustained’, they have been significantly improved.

‘Wakatobi’ is an amalgamation of the names of the four largest islands of what was formerly known as the Tukangbesi Archipelago: Wangi-wangi, Kaledupa, Tomia and Binongko, which lie off the south-eastern coast of the Indonesian province of Southeast Sulawesi. Wakatobi National Park was established in 1996 and now covers 1.4 million hectares, around 65 per cent of which is coral reef. In 2003, the four islands were incorporated into a single, new government district and officially named ‘Wakatobi’.

His resort is built on a small island separated from the western shore of the island of Tomia by a narrow, shallow channel. Mäder’s commitment to the environment is clear from the moment Wakatobi comes into sight. The central longhouse, constructed using traditional Indonesian methods and materials, looks very much at home within its surroundings, backed by a jungle of palm trees and fronted by a white sand beach.

The cabins and private villas are well placed within the resort. Overlooking nothing but the ocean and without a hint of any other human existence for miles around, the site is the very definition of secluded. Although you know that you are about to step inside a premium resort, at first glance it all appears rather, well, rustic.

The interior of the buildings, however, clearly indicates that Wakatobi is anything but basic. All the creature comforts that people expect, and more, are present: air conditioning, minibar, four-poster beds, hot-water outdoor showers and internet facilities; the villas have pools and ocean-scene verandas, but there is nothing overly ostentatious about any part of it.

The eco-friendly aesthetics, however, are only a small part of Wakatobi’s story. Far from being simply a dive and snorkel resort, the establishment was founded upon the principles of environmental conservation by working in partnership with the indigenous population – the Wakatobi Collaborative Reef Conservation Program.

Put simply, in return for them not fishing in certain locations, not using destructive fishing methods such as dynamite and cyanide, Wakatobi pays to lease certain stretches of the reef from the local villagers, provides employment opportunities, and supplies the village with electricity and fresh water.

‘From the first day,’ says Lorenz, ‘it has been a business agreement. That stops the destruction because it’s money. Everybody understands that.’ The collaboration is part of the reason behind the premium pricing of Wakatobi. ‘You can do more with one person paying $1,000 dollars than you can with 10 people paying $100 each,’ Lorenz says.

Mäder’s drive towards conservation came from previous experience in other locations where the development of mass tourism caused a deterioration in the local environment. ‘The usual experience [is that], 95 per cent of people return to a place and say it’s not as good as before,’ he says. ‘And that sucks.’

It’s a common worldwide phenomenon – as areas in developing countries gather popularity as tourist destinations, the locals take advantage of the ecosystems on which they survive to improve their lot in life.

Land is sold for development, fish are caught to supply restaurants, trees are cut for building materials, and in a very short space of time, what was once a tropical paradise becomes an inexpensive tourist hotspot. The surrounding reefs, already under threat from a changing climate, are subject to a pressure that has seen many of them imperilled, devoid of fish, home only to broken coral and suffocating algae.

‘Too many move in, then they compete on price, but don’t spend money on the environment,’ says Mäder. ‘We have paid millions of dollars since we were here,’ he continues. ‘It’s crazy. It’s money we could have used to buy fancy boats or whatever.’

Millions is not an exaggeration. The 24-hour power supply extends to all the homes that house the local village’s 500-strong population; the fresh water is provided by Wakatobi Resort’s own desalination plant; 300 locals are employed by the resort and the collaboration extends to all 17 villages in the regional subdistrict. Schools, conservation projects and patrols of the reef and fishing areas are all sponsored by Wakatobi Resort – and, of course, there’s the resort’s private airstrip, which brings tourists and supplies twice a week to Pulau Tomia on board a 70-seat propeller-driven aircraft.

More from Wakatobi:

This is all a far cry from 1994 when Lorenz first arrived on the island. With no electricity, no engines, no transportation beyond hand-crafted fishing boats, he describes feeling as if he were ‘back in the 18th century.’ He had been inspired to visit after reading in a copy of the Lonely Planet about the province of Southeast Sulawesi (which is the size of Switzerland). ‘There was an outline of the province and one sentence,’ he recalls. ‘SE Sulawesi is so difficult to reach and nobody goes there and that’s why we don’t write about it. Full stop.’

During his extensive travels, Mäder spoke with local village chiefs to find out who was prepared to work with him. With his background in marine biology, he also researched local environmental conditions to determine which location would be best suited to his dream of building a sustainable resort. ‘I didn’t want it to be like other places I worked,’ he said. ‘You know – go there, and after two years it’s gone.’

Just communicating with the locals was not easy. The majority of the native population speak Bahasa Indonesian, but a very important ethnic minority, the Bajau – or ‘Sea Gypsies’, who depend almost entirely on the ocean for their existence – do not. In what he describes as a ‘stroke of luck,’ Mäder found not only a village chief who was prepared to work with him, but a perfect location for coral regeneration. Situated at the meeting of the Banda and Flores seas, cold Antarctic currents drive nutrients and coral larvae to the region, which upwell against Wakatobi’s reefs.

When he first arrived, Lorenz described the tops of those reefs as nothing more than ‘bare rocks,’ upon which, at low tide, 300 people or more would be walking and ‘reef gleaning’ – collecting what resources they could while the reef remained accessible. There was a significant amount of damage to the reef through poor fishing practice, including ‘bomb holes’ made by blast fishing, a tactic learned during the Japanese occupation of Indonesia in World War Two, and which continued using the stores of dynamite left behind after Japan’s surrender.

Most of the holes are now gone, and it’s difficult to apportion any blame to the local population. They had no choice in the matter during the Japanese occupation, and little was known at that time about the impact of human activity on the underwater world. Furthermore, damage to the reefs and fish populations of Wakatobi was not caused solely by the locals. Fishing operations from other nations took vast quantities of fish stocks unchecked, with sharks being particularly vulnerable. A 2014 report from the Scripps Institute of Oceanography suggests that overfishing from the late 1970s to the mid-1990s saw such a decline in numbers, that Wakatobi’s own fishermen were travelling more than 800km to exploit the shark population in Australian waters.

These days, the current Indonesian fisheries minister is sinking boats deemed to be fishing illegally, but in the ‘lawless’ Sixties and Seventies, nobody knew the damage they might be causing, and nobody really cared.

It took two-and-a-half years of working with the local population before things started to turn around on Wakatobi’s reefs. It took considerable effort from Lorenz to convince the fishermen that his expertise was worth listening to, and his constant attention was required to ensure that his ideas were put into practice.

‘It’s not just about throwing money at people and hoping for the best,’ says Lorenz. ‘You have to control it. You give the money, you have an agreement, and you check every day.’ One of his first initiatives was to persuade the local fishermen to close 40 per cent of their fishing grounds to maximise yield over time. Needless to say, this was an unpopular request, but after fish stocks began to noticeably improve over the following four years, the fishermen became his best line of defence.

Once Lorenz had them on his side, they were more amenable to listening to his ‘cool tips,’ which included stopping the practice of chopping up crown-of-thorns starfish (COTS) for use as fish bait. COTS can regenerate from fragments and cutting them up just creates more of them, which then go on to ravage the reef and therefore reduce fish stocks. The locals had also been using the roots of the tuba tree which, when crushed, release a neurotoxin similar in potency to cyanide. It kills fish and coral, but may also have been causing brain damage to the fishermen and the children who were swimming in the poisoned water.

Education alone, according to Lorenz, is not enough to ensure a sustainable programme of conservation. Preservation for the future is not an easy concept to understand for people who live hand-to-mouth. Although educational programmes are an essential part of the Collaborative Reef Conservation Program, they are only valuable, he argues, when run in parallel with the financial aspect of the effort.

‘You have to work together with the locals. Every day. You have to be there. You have to build the trust. You have to be on site,’ says Lorenz. ‘Don’t try to just go to schools and teach them about beautiful fish and all that. If there’s no conservation already happening, everything will be gone before the kids are grown-up,’ he says. ‘It’s not so important at first that everybody understands what it’s all about. But you have to start somewhere. What they understand immediately is business.’

Lorenz runs the business with the help of his brother Valentin. Both are scathing about the activities of some NGOs who, as Lorenz puts it, ‘come out here, cruise around on a boat, have a fun trip for two weeks and go back,’ after which they ‘throw some money’ at local initiatives. ‘That’s not how it works,’ says Lorenz. During a previous chat, Valentin had been even more direct: ‘Don’t talk to me about NGOs!’

The relationships and business arrangements made with the various local communities need to be monitored on a continuous basis. Lorenz has a permanent residence on the island, from where he oversees the technology, construction and politics involved in maintaining a stable relationship with the local villagers to ensure progress.

To the untrained eye, the results of the conservation program may not be immediately obvious. This might sound like an unflattering comment to make in light of Wakatobi’s long-term efforts, but is actually one of the greatest compliments that could be given to its success.

The evidence is observable in the health of the reefs, particularly in the shallower water where the impacts of human activity are most destructive. At these depths, much of the slower-growing species of brain coral, porites and gorgonian fans are a lot smaller than they would be if a reef had remained genuinely untouched for centuries.

They look, in fact, as if they have been growing for approximately 20 years. The reef tops, described as ‘bare rock’ by Lorenz upon his arrival, are filled with the faster-growing staghorn and table corals, and – importantly – seagrass. The latter has suffered an even worse fate than coral in recent years, yet here has re-established a presence on the reef plates.

In terms of diving, Wakatobi is truly spectacular for those who relish coral diving. The reefs are rich and extremely diverse, with currents that remained mild during my time there, apart from one dive where we encountered a slightly uncomfortable ‘washing-machine’ effect. Large pelagics, however, are rare visitors, probably a result of the historical depletion of species that are very slow to reproduce and re-establish, but whitetip and blacktip reef sharks often put in an appearance.

Those seeking larger critters may wish to book a place on Wakatobi’s liveaboard, Pelagian, but what the resort’s reefs may lack in bigger fish is more than made up for by the volume, diversity and colour of the coral, smaller fish, and macro species. The resort has a dedicated, temperature controlled camera room for photographers looking to make the most of the opportunities that Wakatobi provides.

Wakatobi Resort actively promotes snorkelling, not merely as a box to tick on a list of holiday activities, but to be enjoyed as a parallel to diving. The two American women who became my companions for our week’s visit were so enamoured of the place that they had returned just a month after a previous trip and, as non-divers, had deliberately sought out dedicated snorkelling resorts.

There is so much to see on top of the reefs that as the divers boarded and exclaimed about the turtle we had encountered, the snorkellers would tell us about the other five, and also the cuttlefish and the octopus, which had clearly escaped our deep-water gaze.

Top and bottom, there is a huge amount to be found. As Lorenz puts it: ‘you can literally do square-metre dives here,’ he says. ‘Once you learn to see and find the small stuff, it’s incredible. We have at least 400 species just off the beach on the house reef.’

There is little or no evidence of past destruction to the reef, beyond the smaller size of shallow-water corals. Some damage is present but appears to be mostly caused naturally, especially near the surface. There, strong seas can snap some of the more fragile species, but without being pulverised by the repetitive mechanical action of human activity, the likes of table corals continue to grow in situ if left unmolested. Clear indications of a natural ‘avalanche effect’ were present in some locations – the result of a tree, perhaps, collapsing into the water and sliding down the steep-sided reef walls.

The only real blight that we came across was at a reef called ‘Table Coral City’. Wakatobi’s reefs have remained largely unscathed by the ravages of climate change, but the presence of diseased coral suggested that some other factor – possibly COTS-related – was responsible. Indeed, Wakatobi’s resident instructors are involved in a regular COTS eradication programme.

One particular highlight happened above the water, during evening drinks in the jetty bar, situated directly over the fringing reef ’s drop-off. A glowing trail, looking for all the world like some form of ethereal snake, wound its way underneath the jetty, followed a few moments later by a second, and then a third.

As the trails grew in number, the bartender shone his torch into the water and we found the source: a tiny species of shrimp ejecting bioluminescent fluid from its body. How such a small creature could produce such a volume of fluid remains one of nature’s miracles but within thirty minutes, the entire edge of the drop-off was glowing as far as the eye could see in either direction – a perfect mirror to the starlit skies above.

It was a stunning experience and, for me, unique.

The presence of such a phenomenon as a direct result of Wakatobi’s initiatives would be purely speculative, but the resort keeps its ecological footprint small. No chemicals or pesticides that might damage the reef through runoff are used within its boundaries, although the place is kept spotlessly clean, with a service that could hardly be less intrusive.

There are trade-offs, however, and some may be tempted to question the environmental impact of the aircraft that ferries tourists and supplies to Wakatobi, or the generators that power the resort, the village and the desalination facility.

It would, however, involve an arduous journey to reach the resort without the small turboprop aeroplane. Without the income from visitors and the benefits that the villagers receive as a result of Wakatobi’s business strategy, there would be no incentive for the locals to take ownership of the necessity for the conservation of the local reefs. It is a delicate balance, and one which Lorenz is keen to address.

‘There’s always negative impact, there always is, it’s just human nature,’ he says. ‘But if we can improve more than we destroy, if the impact balance is on the positive side, then we can win, long term.’

With its beautiful, secluded location surrounded by vibrant, healthy, coral reefs, all set in an extremely welcoming environment, Wakatobi Resort serves as an excellent model for sustainable eco-tourism.

It would appear that – long-term – Wakatobi is, indeed, winning.

- Crown-of-thorns outbreak developing in northern Great Barrier Reef - 29 January 2026

- Six bodies recovered in search for missing Philippines divers - 27 January 2026

- DIVE’s Big Shot Light and Shadow – win an Aggressor Adventures liveaboard trip - 23 January 2026