The inside story about The Cave – the first feature film about the rescue of the Thai schoolboy football club saved from a flooded cave

Jim Warny makes an unlikely film star. But this quiet, calm and unprepossessing electrician who lives in County Clare in Ireland is slowly getting used to making speeches at film premieres and giving interviews.

For Warny, 37, was not only one of the team of 14 foreign divers who secured the rescue of the Thai football team and their coach from a flooded cave last year, but he also stars in the first feature film to be made about the remarkable story.

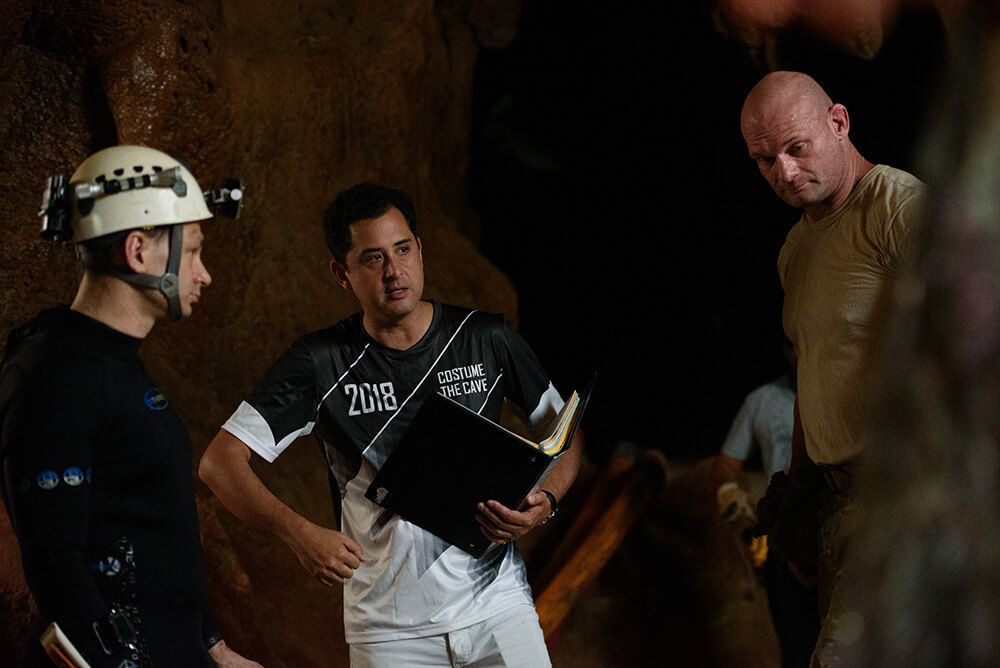

The Cave shown last weekend at the BFI London Film Festival before a cinema release in Thailand next month is an action film recounting the 18-day rescue mission and director Tom Waller made the risky decision to let actual participants play themselves in the drama.

Four of the divers – Warny, Erik Brown from Canada, Mikko Paasi from Finland and Tan Xiaolong from China – take leading roles as does a number of other key protagonists including the local police chief, an indefatigable Thai who supplied the crucial high-powered water pumps which made the rescue possible and an American television reporter.

This imbues the film with some remarkable verisimilitude but at the cost of some, at times, creaky acting. In many ways this gripping film is the result of many fascinating quirks of fate and it is remarkable that it even got made, never mind beat the rest of the world to the punch, including Netflix (which bought the rights to the boys’ and their coach’s story for a forthcoming miniseries) and National Geographic (which has signed up the key member of the diving rescue team, including John Volanthen who located the trapped boys, to help with a major documentary).

The first fortuitous moment was that filmmaker Tom Waller, who has an Irish father and Thai mother and dual nationality, was in Ireland when Jim returned home after the rescue and saw a brief television interview. He tracked Jim down and they met up for a cup of tea and quickly built a strong, trusting bond.

‘It was then I realised I had to make this film,’ said Tom who works as a film director and producer in Thailand with a number of successful features to his credit and has lots of experience working as a line producer when Hollywood filmmakers need to film in Thailand.

Having Thai nationality and being based out there allowed him to quickly put a full crew together and allowed him to avoid all the bureaucratic hoops foreign filmmakers would have to jump through before starting filming.

‘We sort of got in under the radar,’ Waller explained.

However, it wasn’t all plain sailing. The Thai authorities at first refused them access to the Tham Luong caves in Northern Thailand and during most of the rapid production schedule, the team weren’t sure whether they would get permission to even show the film in Thailand.

Necessity being the mother of invention, Waller found a disused swimming pool and some other suitable caves in Thailand and filming began in October last year – just three months after the 12 members of the Wild Boar football team had been brought back to the surface. The Thai authorities relented on access to the caves but only after the main shoot had finished in January this year. However, the team did manage to include key footage of the actors playing the boys entering the cave. And the Thai censor, after seeing the finished film, granted them a licence to distribute it in Thailand.

Warny had been following the events of June 2018 from his home in County Clare in Ireland where he works as a Lufthansa electrician. With more than 20 years experience of elite cave diving, first in his country of birth Belgium and then in France, he knew most of the rescue team of divers assembling in Thailand. He texted and asked if there was anything he could do. A prompt reply asked how quickly he could mobilise. The next morning he was on a flight to Chang Rai.

In his first day in the cave he was helping take stage tanks to a half-way point in the 4km cave system. The next day another diver had problems with his sinuses and Warny was drafted to go even further into the cave and help with the first evacuations of some of the heavily sedated boys.

‘It was a miracle it all went well,’ he said. ‘We were all operating outside of procedures. No one has ever sedated people and moved them through submerged passages before.’

The next day Warny was asked to take on moving one of the sedated team through the bulk of the cave by himself. This, as the film graphically, illustrates was particularly fraught as he had to be quickly instructed on how to administer an injection of ketamine in case his passenger starts to wake up and panics. Which is exactly what happened.

‘I had never so much as held a needle,’ he told DIVE. ‘Never mind actually injected someone. It was very nerve-wracking.’

The rescue team were desperate to get the remaining boys out before the water in the caves started to rise again, following more heavy rain on the hills outside. Warny, as he later discovered, successfully manhandled the boys’ coach, Ekapol Chantawong, through the flooded sections of cave, even having to top up his ketamine levels midway. He was the ninth person rescued and all the other boys quickly followed him out.

In the same way, as the unflappable Warny got more and more involved in the rescue, he became more and more involved in the film.

‘At first, I was bought in to help with the script,’ he explained. ‘Then I got involved with the planning of the diving and things just sort of happened and the next thing I knew I was actually in the film.’

As certain doors closed for Waller and the team as they moved into production, others opened. They located a number of key protagonists including Thai engineer Nopadol Niyomka who supplied the pumps and decision was made to use them in the film rather than actors.

Waller said: ‘We decided to focus on some of the unsung heroes and tell their stories. The international group of cave divers who volunteered. The local farmers who refused compensation for their flooded rice fields so the money could be spent on the rescue. Nopadol who drove his pumps hundreds of kilometres to help. It seemed a natural and sensible thing to include them in the film.’

The inclusion of the divers certainly adds a strong feeling of authenticity to the kitting up and the underwater scenes. Using a number of cameras simultaneously to capture the action, as is common in reality television, provides edge-of-the-seat footage after skilled editing. This becomes the dramatic heart of the film and is its strongest element.

‘I felt, we felt, a special responsibility,’ said Warny. ‘Just like the responsibility, we had during the rescue. We had a responsibility to get it right in the film, to tell the story truthfully. I was only a small part of the rescue but it was crucial to get the diving right.’

Perhaps this is where the skills of the cave diver and the skills needed to recreate the events on film overlap the most. Warny is extremely convincing on screen as the stressed diver coping with his fears and getting the job done.

After a viewing of the film in London’s West End, he told the audience when asked how he coped with the pressure during the rescue: ‘You compartmentalise it. You put all your fears and doubts in a corner and get on with it. Stay calm and get the job done – that’s what cave divers do!’