Five decades after Jaws made a splash in cinemas, what impact did the blockbuster have on shark conservation?

By Melissa Hobson

I don’t remember if I’ve ever, ever been as afraid as I was underwater that day.’ Nelson Nhamússua is a local scuba instructor at Tofo Scuba in Mozambique. In November 2019, he was sweeping a dive – swimming at the back of the group to keep an eye on everyone – when he glanced behind him.

‘I just remember seeing a dark shadow coming towards us,’ he says. The shadow loomed closer and closer until he realised what it was – a great white shark. Heart racing, he couldn’t help but think of the movie scenes where a villainous shark snatches the unsuspecting diver at the back of the group. ‘I almost peed myself in the water.’

After passing them on the dive, the shark cruised by again while the group was doing its safety stop. ‘I was as uncomfortable as I’ve ever been in my whole life,’ says Nhamússua. The visibility at the surface was murky and he just wanted to get back to the safety of the boat. ‘I couldn’t wait for my computer to clear.’

‘You’ll never go in the water again’

The fear that people around the world have for great white sharks is often attributed to the movie Jaws. When the film hit cinema screens in 1975, it introduced audiences to a terrifying villain: the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias). Scientists, however, prefer to simply call them white sharks.

Many people vowed never to step into the ocean again. The US also saw an uptick in trophy fishing tournaments as people channelled Quint, the protagonist in Jaws, and set out to take down enormous great whites.

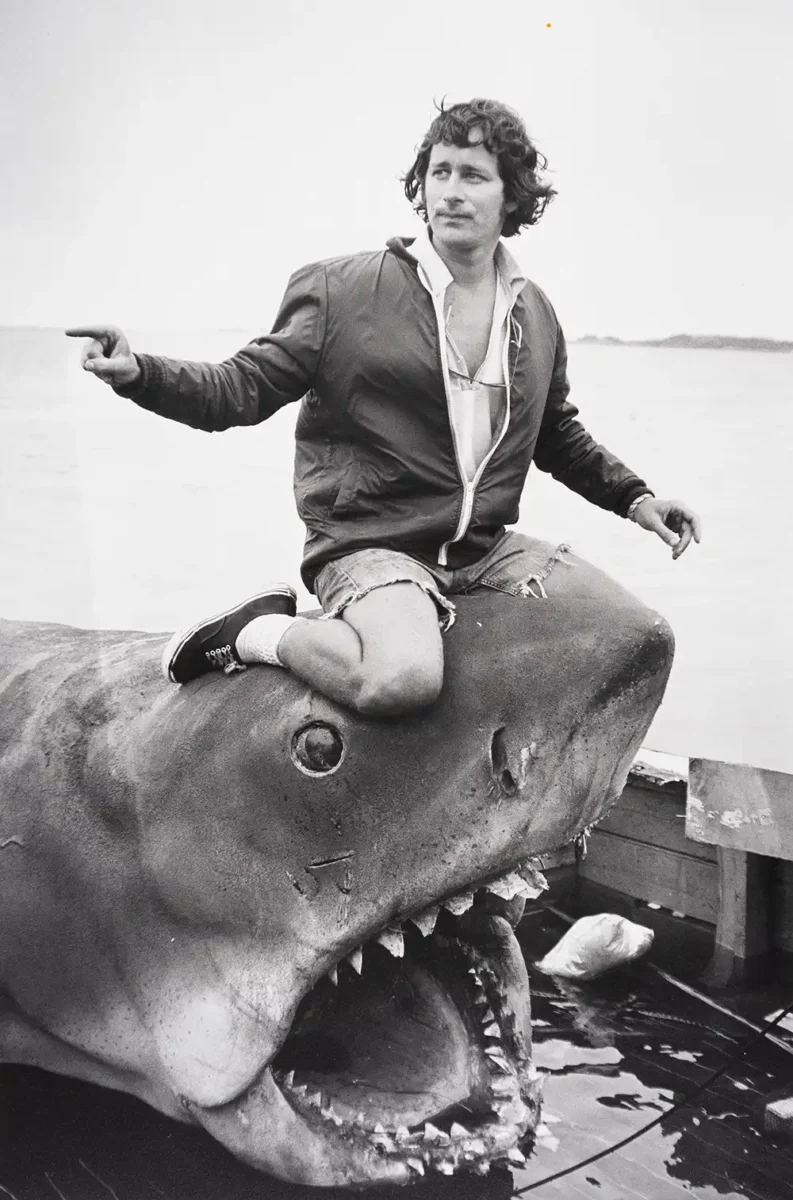

Director Steven Spielberg has publicly shared his regret about the decline of shark populations as a result of the movie, and writer of the original Jaws novel, Peter Benchley, and his wife Wendy later dedicated their careers to marine conservation.

But alongside the negatives, Jaws also made people aware of the plight of these remarkable predators and inspired young marine biologists to dedicate their careers to learning about and protecting sharks. Fifty years on, let’s dive into the impact this iconic film has had on shark populations around the world.

‘When Jaws hit, there was this initial, “It’s so terrifying”, and some people took it as licence to go out and kill sharks,’ says Wendy Benchley, Peter Benchley’s widow (Peter died in 2006). ‘We were really horrified to see that.’

Wendy reflects on the movie in a new documentary, Jaws @ 50: The Definitive Inside Story. The film recounts the spike in shark trophy hunting soon after Jaws’ release as well as the longer term shift in conservation mindsets from the many people inspired to protect these fascinating predators (including those who became marine biologists because of the movie).

But the terror Jaws instilled didn’t happen in a vacuum. People were already afraid of sharks, says shark scientist and conservationist Gibbs Kuguru: ‘Jaws inadvertently added fuel to a fire that was already smouldering in

the cultural zeitgeist.’ This fear was around before Jaws and still simmers for communities around the world.

Like many Mozambicans, as a child Nelson Nhamússua couldn’t swim, even though he grew up by the ocean. He remembers going to the beach as a kid to help his family push their fishing boats into the water and being warned that, ‘If you go deeper than chest level, a shark would take you’. Overcoming this niggling thought in the back of his mind was a huge challenge when he trained as a diver.

Inspiring a generation

Although many people watching Jaws were fixated on the terrifying appearances of Bruce – Spielberg’s nickname for the mechanical shark – others had their eye on another character: the fictional oceanographer Matt Hooper, played by actor Richard Dreyfuss.

Wendy remembers that ‘for every one letter that Peter got saying, “I’m so scared, I’ll never go back in the water”, he got 50 or 100 from people all over the world saying, “I’d like to be Cooper. I want to be out on the ocean learning more.”’

Greg Skomal, shark scientist and author of Chasing Shadows – a memoir of a career researching white sharks – was one of these people. When he saw the movie as a teenager, he was in awe of Hooper. ‘I decided that being a shark biologist looked like the best job on Earth,’ he says. ‘The movie really did inspire me to become what I am today.’

Gibbs Kuguru also credits the movie with steering him towards shark science. Again, the inspirational character of Matt Hooper outweighed any negative portrayal of the predators. ‘His curiosity, bravery, and confidence gave a face to what a marine scientist could be,’ says Gibbs.

‘He’s likely responsible for launching the careers of many shark scientists around the world, including mine. Where would I be without Jaws?’

According to Wendy, Dr Samuel ‘Sonny’ Gruber told her that marine science applications to the University of Miami increased by 30 per cent after the movie’s release.

‘That surge of curiosity jumpstarted a new interest in understanding the ocean,’ she says. Studying and understanding sharks is key for protection efforts.

Shifting mindsets

Over time, people’s attitudes to sharks have slowly changed. ‘There’s a growing wave of people who now see sharks not

as man-eaters, but as misunderstood, vital parts of our ocean ecosystems,’ says Gibbs.

Social media, TV and news stories can be problematic. Sensationalist headlines about ‘shark-infested waters’ and ‘terrifying man-eaters’ blow the risk of being in the water with sharks out of all proportion.

There were 47 unprovoked shark bites in 2024, just four of which were fatal. Compare this to the 85 cyclist fatalities in 2024 in the UK alone. On the other hand, responsible coverage can help to overturn stereotypes and make people see that these fascinating fish deserve protection.

Gibbs cites the shark scientists and conservationists Melissa Marquez, Jasmin Graham and Jess Cramp in particular: ‘They’re absolute heroes in reshaping the narrative.’

Greg Skomal has also noticed attitudes shift through his career. In 2004, a white shark became trapped in a salt pond on Naushon Island, Massachusetts. When a similar thing happened nearby 50 years earlier, he says, ‘that shark was killed immediately by fishermen and viewed as a menace’.

But this time people were afraid for the animal. ‘I had people emailing and calling me and threatening my life if I didn’t save that shark,’ says Greg.

After the release of Jaws, even Peter Benchley realised the true magnificence of sharks. With Wendy by his side, he dedicated his career to conservation. He’d been fascinated by sharks since he was a teen, going fishing with his dad in Nantucket – the sharks would go after the fish they brought in. But it wasn’t until after the movie that a world of opportunities opened up for him to come face-to-face with these iconic animals in the water.

As he learned more, he would tell people that if he had known then what he learned later, he never would have written a book with a shark as a villain, recalls his widow.

Peter dived with white sharks in the Bahamas, South Australia and Guadalupe. His first ever sighting – while building up his scuba diving experience in the Bahamas – was totally unexpected. ‘Peter was coming around a big coral head. The shark saw Peter and was so startled that it flipped around and shit in the water,’ Wendy says.

In March 2025, a group diving with Scuba Junkie Penida in Nusa Penida, Indonesia, had a similar surprise encounter. Just

10 minutes into their final dive of the day, at around 18-20 m deep, a massive shape appeared in the water. It was so big that, at first, they thought it was a whale shark.

These experienced divers were incredibly excited, although they did admit there was a subconscious element of fear in that buzz too. ‘It’s not uncommon for people to be fearful of sharks in general, particularly with beginner divers,’ says Scuba Junkie Penida’s Dani Drury.

White sharks aren’t commonly seen in these waters but there had been an encounter in Nusa Penida’s Crystal Bay in September 2019. At that time, the reaction from dive professionals was polarised, says Dani, with a fairly even split between people who were jealous that they hadn’t seen the shark and those who were so scared that they avoided the dive site afterwards.

Wendy Benchley says that this group was ‘lucky to have seen a great white in the ocean’. Today, with the exception of cage diving, it’s very unlikely that you’ll see one outside a conservation area.

The true villains

‘I’m often asked the question: “Didn’t Jaws lead to the demise of sharks?”’ says Greg. ‘I don’t agree with that.’ Although the movie exacerbated the negative public perception of sharks – something that persisted for many years – he doesn’t believe it can be blamed for the decimation of shark populations in the following years.

Around the same time as Jaws was released, something else was brewing: industrial fishing. ‘It was really the broad-scale development of commercial fisheries that led to the demise of many populations of sharks along the eastern seaboard of the US and beyond,’ he says.

Gibbs agrees: ‘We can’t talk about saving sharks without talking about overfishing.’ Each year, around 100 million sharks are killed globally. ‘If we want a future where sharks still roam the oceans, we need to start lobbying our governments and supporting policies that curb industrial exploitation,’ he adds.

To encourage people to support shark conservation, education is key. By sharing more about the lives of these remarkable animals, we can help divers and non-divers alike understand that sharks aren’t naturally aggressive towards humans, that they play an important role in the marine ecosystem and that there are things we can do to protect them.

Experiencing the beauty of sharks in the ocean is also important – whether that’s a powerful white shark, a lassotailed thresher or a weird wobbegong. ‘Sometimes it takes the person to have a shark encounter to realise that they are beautiful, calm animals and that they’re not a threat,’ Dani Drury says.

This was certainly the case for Nelson Nhamússua. Once the shock wore off, his experience of swimming alongside a white shark without incident helped him realise that sharks aren’t out to harm people. ‘It changed my whole perspective,’ he says. ‘Now, I feel so privileged.’

Today, Nelson feels a responsibility to share his encounter with the next generation. He loves seeing the look on the faces of local kids when he tells them that he swam alongside one of the ocean’s apex predators and lived to tell the tale.

‘I could see they were so excited,’ he says. ‘It’s changing their way of thinking about sharks.’

Jaws @ 50: The Definitive Inside Story is now streaming on Disney+ and Hulu.

More great reads from our magazine

- ‘Rays of Hope’ – an Interview with Karen Fuentes, founder of the Manta Caribbean Project

- ‘Taking Stock’ – expert tips on becoming a stock photographer

- ‘Voyage of Discovery’ – finding new dive sites in Raja Ampat

- ‘Machine learning’ – an interview with Blue Machine author Helen Czerski

- ‘Pierless’ – the myriad photographic opportunities of Barbados’ Cement Pier