Artist and conservationist Francesca Page travels to northern Sumatra to report on a local project safeguarding the future of shark and ray populations.

Words, photograph and illustration by Francesca Page

As the world’s largest shark-fishing nation, Indonesia faces a pressing conservation challenge. I journeyed to Sumatra’s northern shores to witness firsthand an unconventional alliance in action aimed at saving critically endangered sharks and rays while also safeguarding the livelihoods of coastal communities.

In a small fishing community, a project is being trialled where local fishers are being paid to return endangered shark and ray species to the ocean when they find them in their nets. Called Kebersamaan Untuk Lautan (KUL), which means Togetherness for the Ocean, the project aims to protect dramatically depleted species such as wedgefish and scalloped hammerheads, and financially help the local fishers.

The project is led by conservation scientist Dr Hollie Booth. Over a coffee, she explained the basic concept: ‘Fishers are heavily dependent on fisheries for their income and livelihoods. They’re not necessarily targeting sharks and rays, but the sharks and rays just hang out where the other fish hang out.’ This means that they are often caught alongside the other catch and sold.

Her plan to pay the fishers to release endangered bycatch, reflects her stance that people and nature are intrinsically linked and ‘all lives, human and animal, deserve moral consideration’.

Since the project began in 2022, more than 1,000 critically endangered sharks and rays have been safely released. This initiative safeguards marine life and sustains the livelihoods of the fishers and their families – a true win-win scenario.

A thick smell of clove cigarettes hung in the air early the next morning as I hopped from one elaborately painted boat to the next to reach the fishing boat we would be joining for the day. I’m with Ilham Fajri, a shark researcher and my guide for the week.

After an hour of sailing, we reached our first gillnet of the day. These expansive nets, spanning 300 metres and positioned 30-40 metres deep, ensnare any creature unfortunate enough to cross their path. As I leapt into the water to watch the retrieval of the vast net, what unfolded left a lasting impact on me.

Despite the fishers’ lack of intention to target sharks, the volume of shark bycatch I witnessed was staggering. Over 80 per cent of the catch comprised of baby or juvenile sharks.

From the depths emerged a figure – a critically endangered smoothnose wedgefish. It is slowly hoisted towards the boat. I dive down, push the trigger and get the shot.

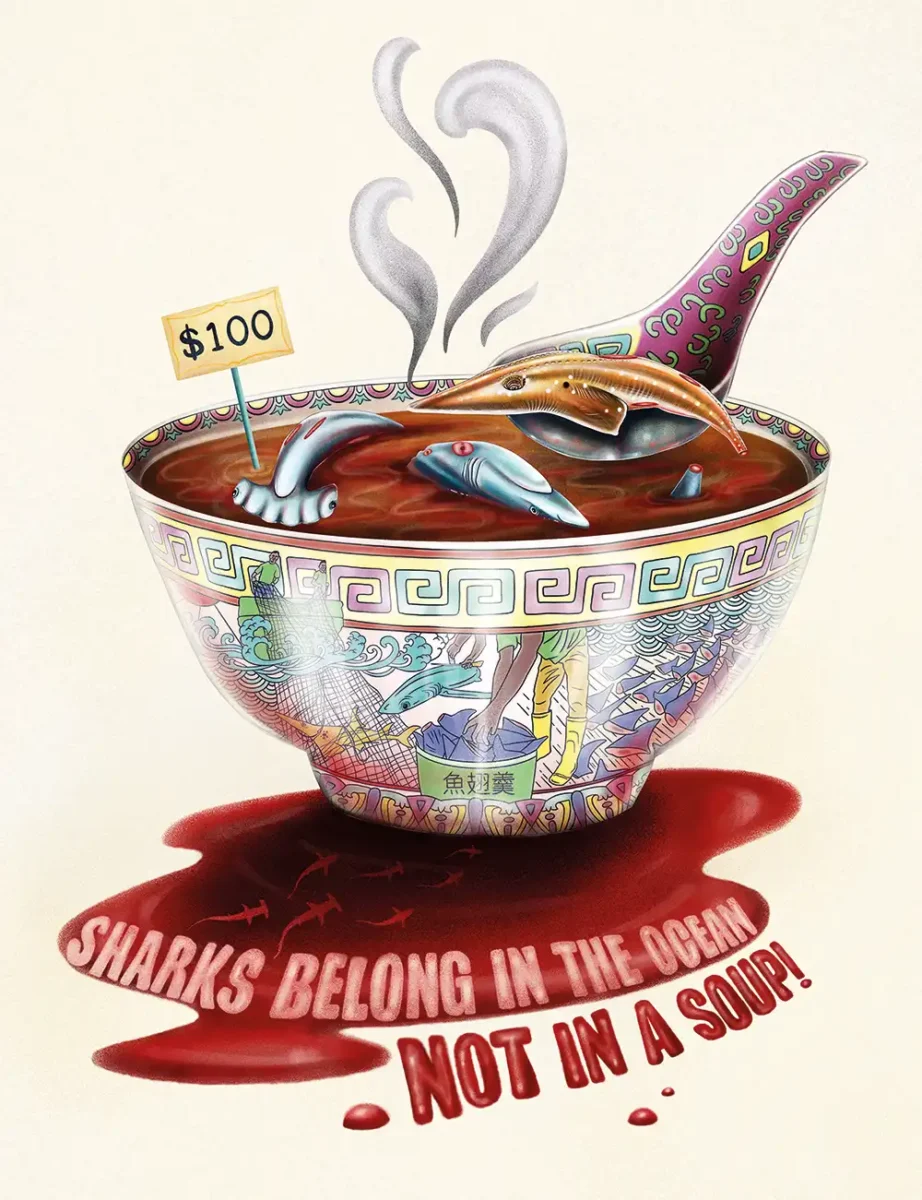

Most wedgefish are critically endangered, primarily due to overfishing. Hollie later told me: ‘Their large dorsal fin is one of the most valuable fins in the international fin trade.’

An 18cm wedgefish fin can sell for 10 million rupiah ($600 USD) in local markets. The remaining meat is used locally, often found in fish curries at roadside ‘Warung’ stops. This lucrative bycatch helps to supplement fishers’ otherwise modest earnings from the sea.

Ilham said that fishers previously discarded sharks, but now, due to the demand for fins, shark meat consumption is also on the rise.

As a type of ray, wedgefish are primarily found on soft, sandy bottoms. Their adaptations allow them to oxygenate their blood by pumping water over their gills, enabling them to remain stationary. This is unlike many other sharks and rays which need to continuously swim for respiration.

This evolutionary trait is crucial in their survival within fishing nets, contributing to their successful release in the KUL programme. Fishers report leaving their nets submerged for 12 hours, yet many wedgefish are found alive when they are pulled up, allowing the fish to be safely returned to the ocean.

As the beautiful smoothnose wedgefish is hoisted onto the boat, waves splash against the hull. I watch as Sajali, a local fisher and the village’s Panglima Laôt (the title of the local fishing community’s leader), carefully removes the sharp plastic netting ensnaring the wedgefish. He gently lowers the ray to the water’s edge, its eagerness for freedom evident in its wiggles and splashes.

To document their releases, fishers use small waterproof cameras supplied by KUL. To qualify for payment, they must capture a video of the shark being released and swimming away safely. The project is funded by the Save Our Seas Foundation and the UK Darwin Initiative and has the support of the Indonesian government, which provides equipment and personnel to monitor the daily catch.

Back on shore I joined Kusuma, the local officer for KUL, conducting interviews with fishers. Each day, he visits all participants in his village to collect the footage. I met Adliyas, hailed as the ‘shark hero’, who has proudly released the most sharks among his peers, turning it into a friendly competition.

With infectious enthusiasm, he exclaimed in Achenese: ‘I love releasing sharks.’ Some of the other fishers joined him is shouting ‘Yee Baji’ and ‘Yee Rimbah’, words for wedgefish and hammerhead shark in the local language.

One of the many interesting things that Hollie’s research has unearthed is that the local fishers not only value the payments, but they also really enjoy releasing the sharks and rays and get a sense of wellbeing through doing so.

Hasbi, another Panglima Laôt from a neighbouring village, approached me to discuss the profound significance of the project to their community and culture. Achenese people, deeply rooted in tradition, have historically safeguarded their local environment, considering the sea as an ancestral legacy worthy of the utmost care.

The following day, I went to another of the project’s initiatives. I boarded a wooden fishing boat laden with scuba diving gear. The engine’s hum guides us into the blue, where Rusdi, a local fisher-turned-scuba diver, helps me gear up.

We descend 25m onto the sandy bottom check out some recently developed fish traps. These traps, resembling oversized lobster pots, minimise bycatch and maximise targeted fish catch. Covered with palm leaves, they act as aggregation devices, creating small ecosystems teeming with marine life such as cuttlefish and squid.

While the traps incur higher costs than gillnets, increased funding and project support could encourage a widespread transition, safeguarding the local coastline for years to come.

The project’s next steps hinge on securing sustainable funding. One of the avenues being considered is linking the project to ecotourism. With the economic value of shark tourism in Indonesia reaching $22 million annually, Hollie, along with her research team from the University of Oxford and the London School of Economics, has surveyed more than 1,000 marine tourists.

A staggering 96 per cent expressed support for the initiative, which prompts the question: Would you pay to scuba dive and save sharks? Establishing a conservation fund could offer a solution for areas where ecotourism isn’t a direct alternative.

Dive hotspot Pulau Weh in North Sumatra holds promise, as Hollie and her team explore how diving tourism can collaborate with conservation projects to safeguard sharks.

Reflecting on the week, I’ve witnessed bycatch, shared laughter with fishers, and experienced life-changing moments. Saving sharks is complex, but by working with fishers it is possible to find solutions.

These fishers, dedicated to their ocean, embrace the opportunity to contribute to a pioneering project uniting people and sharks for a brighter future.

Francesca Page is a photographer, artist and environmentalist – find more from Francesca at her website www.francescapageart.com

More great reads from our magazine

- Mexico’s Tren Maya is destroying Yucatán’s cenotes

- Working Together- Mexico’s bull shark dives

- Nitrogen Narcosis – beware the rapture of the deep

- Fiji’s Pacific shark feeding boom

- The ride of your life! Scootering with Maldives grey reef sharks