If you are looking for high-energy encounters with the big stars of the ocean, the Galápagos, Cocos, Malpelo & Revillagigdos in the Eastern Tropical Pacific are the places for you – rugged, unforgiving and, at times, terrifying

When the topic turns to the ultimate in adventures underwater, one geographical location springs to mind: the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean. Here, around the isolated and far-flung islands of the Galápagos, Malpelo, Cocos and the Revillagigedos, virtually anything imaginable involving the big animals of the sea is not only possible, but is often routine!

It is the one locale where witnessing mind-blowing phenomena and being a participant in extraordinary encounters beyond the imagination has a very high probability.

This call to adventure is answered in the waters adjacent to a select few islands – 26 in total (three solitary islands and two archipelagos) scattered across an enormous seascape.

This vast expanse of ocean is in a perpetual state of turbulence from competing current flows and wind-driven waves travelling vast distances. The waves unleash their accumulated energies with an explosive power upon these island specks – the first terrestrial obstacles they encounter.

The topography is not pretty in a classical sense. The underwater vista lacks the multitude of colour and variety of living structures of a healthy Indo-Pacific coral reef.

There is, in fact, relatively little coral – a few species of stony coral rather weathered in appearance. It is a forlorn, stark, and primaeval backdrop: massive stone formations the size of houses or city blocks; sheer cliff faces extending above sea level and descending into the depths; escarpments and ledges, overhangs and undercuts; gargantuan rocks and massive boulders dominate the subsea terrain.

The colour palette below the surface is limited to a pale khaki to chalky-white in places, with fissures and gouges of black, otherwise, it is a universe of greys from light to dark. The stark contrast between the scale of the formations and the absence of distracting or pleasing colour makes for a very dramatic but uneasy arena.

To be sure, the seascape has a handsomeness – the word people use when they mean strong-featured but not soothing or serene – and a rugged kind of beauty of naked geological formations and structures well-worn over time.

The rock faces are minimalist in the extreme and austere, not featureless, but scarred with crevices. Rock clefts are filled with long-spined sea urchins, home to eels and nocturnally active fish, as well as invertebrate and fish species that provide parasite removal cleaning stations.

Spiny lobsters wave their antennae as if conducting symphonies while tucked back into recesses as deeply as they can wedge themselves. Guineafowl pufferfish and hogfish meander from crevice to crevice seeking unwary crustaceans caught out in the open.

Colonies of pale purple barnacles by the thousand have affixed themselves to the rocks as best their biological adhesive allows. Tiny blennies stare out from abandoned barnacle shells and cracks in the rocks.

Floating in the midwater are swarms of creolefish, picking plankton from the water column and moving rapidly, en masse, to safety whenever a predatory snapper or hunting pack of jacks enter the area. In addition to the fish that are found in other parts of the Pacific, there are, in the entirety of the Eastern Tropical Pacific, 1,200 endemic fish species.

Perhaps because the setting is so similar and repetitive, and, after a time, even monotonous, it is the sudden appearance of a big animal or animals that transforms a lacklustre seascape into an amphitheatre of the fantastic. Just as an empty stage helps an audience focus upon a main character in a performance, so too does the sudden appearance of a giant oceanic manta ray – or a school of hammerhead sharks, for example – relegate the dull and austere surroundings to a background role which enhances the star attraction.

The marine cast list

The roll call of animals that are often encountered during a week’s scuba diving here ticks a good many boxes for those driven by bucket list aspirations: scalloped hammerhead sharks in sizeable schools; enormous oceanic manta rays; bottlenose dolphins; schools of bigeye jacks; silky and Galápagos sharks; moray eels; sailfish; hawksbill and green sea turtles; balls of baitfish attacked on all sides by opportunist predators; whale shark appearances; fast-moving tuna on the hunt…

The islands of the Eastern Tropical Pacific are the Revillagigedo Archipelago of Mexico; Cocos Island, Costa Rica; Malpelo Island, Colombia; and the Galápagos Archipelago, Ecuador. (There is also one distant island atoll at the western frontier of the Eastern Tropical Pacific, namely Clipperton Island, claimed as French Overseas Territory, which is the most remote of them all. The limited number of expeditions visiting Clipperton has failed to find anything approximating the impressive marine biodiversity found at the other two islands and two archipelagos.)

Each of these remote, remarkable islands shares a common trait: they are the terrestrial-protruding outcrops of underwater mountains, all of which rise precipitously from the surrounding seafloor plateau 350–1,000m (or more, in the case of Malpelo).

These mountain peaks cum oceanic islands are the uppermost formation of rock ridges made up of other crags and seamounts (underwater mountains that do not appear above sea level), themselves the remnants of volcanic hotspot activity and perpetually, if incrementally (on the order of two inches or so per year), moving along their respective oceanic plates (the Cocos Plate, Nazca Plate, and Pacific Plate) through the action of plate tectonics.

These massifs are geological formations characterised by sheer profiles that deflect deepwater undercurrent flows, thus creating an upwelling of nutrient-rich nourishment from colder, deep water currents to the near-surface waters and a down-welling of warmer surface waters – and the attendant greater concentration of dissolved oxygen – to depths that would otherwise be cooler and oxygen-deficient, expanding the range of habitable environments for many species.

This creates an area of high productivity and serves to concentrate and retain every component of the ocean’s trophic level, from the primary producers (phytoplankton) to primary consumers (zooplankton), to secondary consumers, tertiary consumers and apex predators.

This concentrating effect is crucial, for although the Eastern Tropical Pacific has the richest biomass of sealife per square kilometre than any other region of the world, it is also immensely large and spread out, scattering the distribution of the multitudinous organisms far and wide except at these way stations at the oceanographic confluence of geology and currents.

For those seeking to experience the Eastern Tropical Pacific, it has to be said that the conditions can be some of the most difficult diving and most uncomfortable diving you can contend with, not to mention the factor of a very real possibility of physical danger.

To dive the islands of the Eastern Tropical Pacific, one will often be faced with strong currents, to either ride along with as part of a dive plan, or to scrupulously avoid, as part of dive survival. And sometimes a combination of both strategies are required to maximise the opportunities to encounter big marine animals that themselves need not fear currents but effortlessly utilise them.

There are currents so strong, so intense and powerful that humans cannot make headway against them and any resistance is futile. Currents that can take the unwary great distances out to sea and way from the reference of the island, or worse, down currents that can seize a diver and pull the diver down into the abyss rapidly, forcefully, one hundred metres or more – and beyond the diver’s ability to reach the surface alive again. It is a place for caution and respect; the foolhardy and the reckless are rarely seen again.

Just as vexing as currents is the frequent occurrence of surge. Surge is the massive, rhythmic, displacement movement of an area of water by the arrival, expansion and contraction, and return to equilibrium of large waves swells as they pulse across the Pacific and abruptly encounter a stationary obstacle, in these cases, the remote island in the path of the swell.

With surge, a diver is lifted towards the surface, uncontrollably and rapidly, and then pushed downward just as quickly and unpredictably with every pulse of waves as seawater is displaced by wave swells, sometimes with the peak and trough separated by ten metres. The change in pressure of ten metres in a matter of seconds can be very difficult for many divers and can cause barotrauma to the ears.

Once one is resigned to strong currents and surge, thermoclines of cold water intruding unpredictably into a tropical dive venue, occasional diminished visibility and the presence of large marine predators, only then can one competently consider diving in a place where anything is possible.

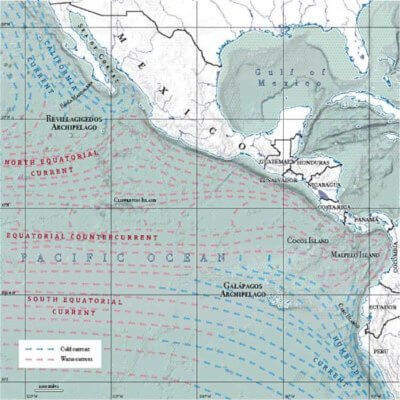

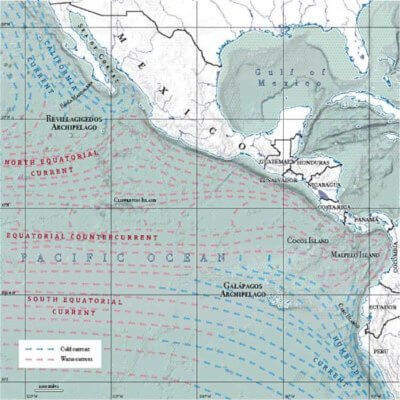

As a distinct body of water, the Eastern Tropical Pacific seascape comprises an area of 21 million sq km – or roughly, an area greater than the size of three Australias or two Europes – and geopolitically includes the sovereign waters of 12 nations.

Its terrestrial border is the west coast of the American continent, straddling both hemispheres and extending south to north, from Cabo Blanco, on the coast of Peru, South America, moving northward up through Ecuador and transiting the equator to include Colombia and continuing onwards, along the coasts of the Central American countries of Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras, El Salvador, and Guatemala, and continuing on into Mexico, following the coast, incorporating both the shoreline of the Sea of Cortez and its waters, continuing around the southern tip of the Baja California peninsula and north again to Bahia Magdalena on Baja’s west coast. From Bahia Magdalena, the boundary extends, in a southwesterly direction, far offshore out into the Pacific, the westernmost boundaries is considered to be the 150 degrees west longitude where it merges with the North and South Equatorial Currents and they coalesce into the East Pacific Barrier – a 5,000km-stretch of water without landfall until the Kiribati (Christmas) Islands. The northwest and southwest margins are where cold-water currents moving from higher latitudes to lower latitudes deflect westward – Humboldt Current in the south and the California Current in the north.

The Humboldt Current, also known as the Peru Current, fuelled by winds and the South Pacific Gyre, is the largest upwelling system in the world, bringing cold, nutrient-laden waters from Chile and Peru into the Tropical Eastern Pacific. Although this seascape represents less than one per cent of the global ocean surface, it is estimated 20 to 50 per cent of the world’s oceans biological production occurs in this fraction of the pelagic realm, with the Humboldt Current alone accounting for 20 per cent of the world’s fish landings, primarily in sardines, mackerel and anchovies.

The Humboldt Current bathes the Galápagos Archipelago with a profusion of life and the fuel required to drive the entire spectrum of the oceanic food web. Its counterpart at the northern extent of the Eastern Tropical Pacific is the California Current. The California Current fulfils the same role as the Humboldt as it flows southward along the coast of North America, with its origins off the coast of British Columbia, Canada and brings nutrient-rich water down the western seaboard of the United States to terminate at Baja California and brings its superabundant productivity to the Revillagigidos Archipelago.

The dynamic marine environment found at these oceanic islands is reliant upon the perpetual interplay of competing currents vying for dominance seasonally. Current is life and currents drive the seasons in the sea in the Tropical Eastern Pacific.

Cocos Island, 550km from Puntarenas, Costa Rica, and Malpelo Island, 500km from Buenaventura, Colombia, are separated from each other by 627km of open ocean yet their seascape is defined by their shared current influences the Panama Current, the North and South Equatorial Countercurrents, and the Colombian Current. To humans, the distances between the two islands are vast, but to the marine life, they are, to a degree, interconnected. A recent study of hammerhead shark migratory movements documented connectivity between Malpelo and Cocos Islands, as well as connectivity with the northernmost of the Galápagos Islands, 1,200km distant from Malpelo.

Malpelo Island

Of the two islands, Malpelo, on its best day, offers up the stuff of interminable bragging rights: a place where, at the right season, and with good luck, one may encounter enormous schools of silky sharks numbering in the high hundreds. Whale shark sightings are commonplace. Schools of hammerhead sharks provide a focus to many of the dive sites and often in relatively shallow water.

Malpelo is renowned for its unique aggregation of fine-spotted moray eels (Gymnothorax dovii) that may be found by the dozens or more, cohabitating on the current-swept, barnacle-encrusted boulders of the rocky undersea topography of a site called Altar of the Virgin. If one descends to 65m, at the dive site called Bajo del Monstruo, there is a possibility of seeing the rare, 4m-long, smalltoothed sand tiger shark (Odontaspis ferox).

At many locales, schools of bigeye jacks move with the surge as waves move volumes of water up and down the rock faces of the Island, the energy that has travelled across kilometres of open ocean releasing itself in an explosion of froth and crashing sea.

The island itself is home to a small contingent of Colombian Navy personnel stationed at the top of Cerro de la Mona, 100m above the wave-crashed boulders that ring the large rock that makes up the majority of the island. There are no beaches or landings, it is simply an isolated rock with a few pinnacles arrayed around its base. Masked boobies tend to nests among the crevices in the massive rock face and the walls are streaked with guano as they have been since time immemorial.

Malpelo appears fairly lifeless, but is home to a few endemic lizards and an endemic crab. It has no discernable vegetation, save lichen, and it calls to mind the phrase ‘godforsaken rock’, which no doubt the naval officers stationed upon Malpelo for long periods of time might agree. But when the action is on and the sea life is abundant and conditions manageable, the phrase ‘godblessed’ may come to mind as well.

In 1995, the Malpelo Fauna and Flora Sanctuary was created to advance conservation measures, however, illegal fishing regularly occurred. In 2005, the government stepped up its commitment and made a resolution extending the sanctuary from 65,450 to 857,500 hectares. In 2006 it was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Yet, in spite of being 500km from shore and surrounded by deep water, adjacent to a 4,000m-deep trench, Malpelo can at times, also offer… nothing. There are times when the water clarity is reduced to a green soup with less than 10m visibility. There are also times when the hammerhead sharks are few and far between. Usually, it is when there are no dominant currents bringing their magic to this isolated collection of rocks. The water may be too warm, or it may be too cold, or, for whatever reason, the circumstances work against concentrating sea life near the rocks and diveable depths and the trip is a bust. It is one of the biggest gambles for the traveller seeking the adrenaline rush of big animal action. Sometimes, it just doesn’t work out at all. And there is rarely a rhyme or reason, only opinion and some superstition about luck.

Cocos Island

Coco is high-peaked, with four mountains and 100m cliffs on all sides; 8km x 3km in size; a lush, green island, which receives 7,000mm of rainfall annually, and boasts as many as 200 waterfalls. It has two major bays with beaches, and many substantial islets adjacent to the central island. It is located 550km from Puntarenas, Costa Rica, and has held a great fascination for many of its visitors over the centuries, serving as the inspiration for Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island and Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park, as well as the original film of King Kong. It has been a Costa Rican National Park since 1978 and was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1997.

Its offshore dive sites Alcyone and Dirty Rock are world-renowned for consistent schooling hammerhead shark encounters.

The shallow water garden of Manuelita Island has most of the island’s 30 species of coral and many of the island’s 300 species of fish, but is especially famous for its population of whitetip reef sharks that cooperatively hunt in packs in the late afternoon and especially at night. In recent years, a number of tiger sharks have taken up residency at Cocos and are most frequently seen around Manuelita Island.

Though not predictable, whale sharks and manta rays often make surprise appearances to divers at various Cocos Island dive sites. At 30m on the sand and rubble slope of Lobster Rock, the odd-shaped and bottom-dwelling redlipped batfish, (Ogocephalus porrectus) (uncharitably described by one prominent writer as having ‘the face of a mummified hooker’) can sometimes be found. It perches upon its fins, as if on tippy toes, searching the rubble for tasty crustaceans and holds motionless to avoid attracting any predators.

At certain times of the year, large schools of small fish pass through the area, where they hunted are relentlessly by yellowfin tuna and bottlenose dolphins, wahoo and rainbow runners, silky and Galápagos sharks, and seabirds.

These small fish form polarized schools in an effort at defence through overwhelming numbers but predators opportunistically hunting together can reduce these vast schools into bait balls and ultimately into a fine rain of fish scales drifting into the depths in a matter of days.

The Revillagigdos Archipelago

The Revillagigidos Archipelago is called Mexico’s ‘Little Galápagos’ due to their isolation and unique endemic species on land, however, it is underwater, where the islands have become most recently well-known for its spectacular marine life.

The Revillagigidos is located southwest of Cabo San Lucas, at the tip of Baja California. Its ‘closest’ island to the mainland is San Benedicto, 390km offshore.

San Benedicto has become famous to divers around the world for a dive site called El Boiler so named because, the top of it rises so close to the surface that in rough seas or at low tide the waters above it appear to boil. It is a small guyot, roughly oval-shaped, more or less the size and shape of a football field, that rises from the bottom 35m below and reaches to just below the surface on the northwest coast of the island. It is covered in patches of coral and is home to lobsters, octopus, and reef fish. The sides of the pinnacle are patrolled by jacks and silky sharks. And mantas. Lots of mantas.

It is not uncommon to have eight manta rays soaring the currents around El Boiler and visiting cleaning stations where clarion angelfish (Holacanthus clarionensis) flock to them and begin a service of pecking parasites from the surfaces of their bodies.

The manta rays also carry the hitch-hiking suckerfish sharksuckers (Echeneis naucrates) and remoras (Remora remora) and the remoras are often infested with parasites making for an angelfish feast.

For reasons unknown, the manta rays at San Benedicto appear to enjoy limited interaction with scuba divers, often slowing to a slow speed and stalling above the bubbles exhaled from the divers’ regulators and bathing in the expanding bubbles as they burst and dance along the mantas’ undersides.

It is believed the mantas enjoy the sensation like humans respond to tickling. There is a strict no-touching (and especially a no manta ray riding) policy enforced by all boats that allows the manta rays to control their level of interaction with the divers rather than being molested by thoughtless and ill-mannered tourists.

Manta rays are also often commonly seen at the anchorage on the opposite side of the island.

Nearly 50km to the south of San Benedicto lies Socorro Island. Socorro also has manta ray cleaning stations as well as some pinnacles where schools of hammerhead sharks are often seen. Bottlenose dolphins visit sites, such as Cabo Pierce, almost daily and long encounters are a frequent occurrence.

A further 315km to the west of Socorro is the infrequently visited Clarion Island. Not much is known about Clarion other than it is still relatively unexplored.

A 120km to the west of Socorro lies a lonely pinnacle, Roca Partida. It is situated upon a broad, flat-topped seamount, or guyot, in 80m of water, 30m height jutting from the sea and 100m wide.

Roca Partida is a magnet for sealife in the area: yellowfin tuna frequently race past the rock looking for unwary prey, shoals of Pacific creolefish (Paranthias colonus) that form thick clouds in the upper water column disappear with an audible whoosh at the arrival of the yellowfin tuna.

Silvertip sharks can be seen at 30m or deeper. Whitetip reef sharks lazily coast on currents next to the rock face, they also form languid pileups on the few ledges that are large enough to support them and keep the current and surge from unceremoniously evicting them from their perch and flinging them into the open waters surrounding. Manta rays frequently pass by, as do bottlenose dolphin, whale sharks and Galápagos sharks.

From February to April, humpback whales migrate from their high latitude feeding grounds to utilise the Revillagigidos Islands as a breeding ground and for delivering and nursing their offspring. In recent years, there have been many documented encounters between divers and humpback whales at Roca Partida in particular, where whales have shown an extraordinary tolerance towards scuba diving interlopers, allowing close approaches and photography from mere metres away from these 14m-long giants.

For decades, fishermen have made the long and turbulent crossing from the mainland to reap the marine riches of the Revillagigidos, often to the extent of virtually strip-mining the region of all fish, sharks in particular. Fortunately, the Mexican government has declared the islands a Biosphere Reserve and a Marine Protected Area with a complete ban on fishing within 12km of each island. Unfortunately, enforcement is inconsistent at best, and often non-existent, in practice.

Few other places can offer visiting divers reliable encounters with giant manta rays, whale sharks, dolphins, humpback whales, tuna, pelagic fish and many shark species. It is of vital importance for the islands to be protected as a national priority for the future of the people of Mexico and for the biological heritage of the entire world. The inconsistent enforcement of illegal fishing is the main holdup keeping the Revillagigedos Archipelago from joining the United Nations World Heritage List.

The Galápagos Archipelago

To the far south of the Eastern Tropical Pacific, straddling the equator at 970 km west of Ecuador are ‘Las Encantadas’ – the Enchanted Islands – known as Galápagos. The 19 islands of the archipelago are spread out across 45,000 sq km of the Eastern Tropical Pacific.

Due to nearly two centuries of research, beginning with shore visits and specimen collection during the first geographical and zoological survey of the islands by the HMS Beagle and its young naturalist Charles Darwin in 1835 through years of dedicated research by scientists affiliated with the leading centres of learning from around the world, the islands are internationally renowned as the tangible, natural showcase for endemism and the living exposition of both the theory of evolution via natural selection and the hypothesis of island biogeography.

In these isolated islands, terrestrial and avian animals evolved so suited to the intricacies of their immediate island environment that they live nowhere else, such as the various subspecies of Galápagos giant tortoise (Chelonoidis nigra); the various subspecies of finches and mocking birds; the marine iguana and Galápagos penguin, as well as many others.

The warm surface waters delivered by the south-westward flowing Panama Current maintain a tropical boundary current for the north-eastern Galápagos. Its influence manifests itself with warmer surface sea temperatures at the two northernmost islands of Darwin and Wolf. From January to May, the northeast trade winds dominate and the Panama Current influences the Central Galápagos with warmer surface temperatures as well, displacing the influence of the cold water Humboldt Current that dominates from June to December.

Darwin and Wolf Islands are essentially tropical diving, albeit with a cooler water thermocline, a crucial element that makes the area so appealing to residency for scalloped hammerhead sharks. Darwin and Wolf Islands together are considered to be one of the best locales in the world to predictably see schools of scalloped hammerhead sharks, Galápagos sharks, and, in season whale sharks. Recent research has determined that as many as 695 pregnant female whale sharks may visit Darwin Island annually as a rest stop on a migration route to pupping grounds estimated to be somewhere in the northwest part of the Eastern Tropical Pacific.

The Cromwell Current, also known as the Equatorial Undercurrent, flows eastward at depth bringing colder water and further nutrients and oxygen-rich waters. It creates an upwelling to the west of Isabella Island which accounts for the presence of numerous whale species and fuels the massive schools of small fish that are the main prey of sea lions, sharks and other piscivore predators such as penguins.

On the west coast of Isabella Island lives the world’s only marine lizard, the wholly vegetarian marine iguana (Amblyrhynchus cristatus), the cold waters are the perfect habitat for the type of macrophytic algae they eat; warmer waters have other marine plants dominating that are not suitable food for the iguanas and thus, although the warmer water temperature might make their energy requirements less demanding as ectothermic animals, they would in effect starve to death.

In times of elevated sea temperatures, such as El Nino Southern Oscillation Events, the algae has a swift die off and the marine iguanas starve and their population numbers crash. On several islands dominated by colder waters and host to profusions of small species of schooling fish, the world’s only tropical penguin, Galápagos penguin, (Spheniscus mendiculus), can be encountered.

The continual battle for dominance of the competing sea currents regulates the sea temperatures which in turn determine which animals will live and thrive in the Galápagos Islands, with the patchwork of cold water and warm water environments offering specific niches. There is nowhere else in the world like the Galápagos Islands and since 1986, the islands have been declared a Biosphere Reserve by UNESCO, further including the marine component in 2001.

The best of dives, the worst of dives

In order to experience the best diving sites of the Eastern Tropical Pacific, one must not only make a substantial financial commitment but also have to tolerate a plane journey to the foreign host country, and upon arrival, an overnight stay, and then undergo a tedious, long and frequently uncomfortable boat journey, of 24 hours or more, each way, across a vast expanse of open ocean to arrive at the particular island chosen that serves as the dive destination. The amount of time required to reach these crown jewels of the Eastern Tropical Pacific can be a soul-destroying barrier to entry for many divers, but for those who endure, the rewards can be out of this world.

It truly is the only place where the big animals of the sea – schools of scalloped hammerhead sharks, whale sharks, manta rays, dolphins, shoals of fish, whales, sea turtles, and more – may be encountered in great numbers, or all at once.

However, just as this description of the delights of this special region sounds irresistible, too good to be true, beware: it is. A visit can really be either as good as the description bears – and, occasionally, even better – or the converse occurs, with almost no middle ground. The Eastern Tropical Pacific also is, enigmatically, a place where one can be confronted with almost nothing interesting or out of the ordinary – and without appreciable cause, without pattern, without warning.

And so, to seasoned divers, it is a port of call alternately exhilarating and frustrating by turns, and by luck, bad and good, and a destination that requires determination and stamina to visit because it is a place where adventures with big animals can and do happen. The Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean is a place that can take your breath away or bore you to tears. It can be the best of dives; the worst of dives… But you would be a fool not to experience it for yourself!