Dr Adel Taher – the highly respected and much-loved director of the diving medical clinic in Sharm El Sheikh – was a pioneer of Red Sea diving. He talks to Mark ‘Crowley’ Russell about the innocent fun and wonder of being the first to dive what are now world-famous reefs and wrecks

Special thanks to Fady Atiya for the use of his late father, Farid Atiya’s photographs

Many visitors to the Egyptian Red Sea will have seen old pictures from the late 1970s and early 1980s of the first dive operators bringing tourists to what is now one of the world’s foremost diving destinations.

Pictures of Bedouin-style tents and old Jeeps leaving tracks in the red sand on the rocky Red Sea shoreline; the first structures to appear on unspoiled shores before hotel cities arose; the days when the global, multi-billion-dollar industry that scuba diving would become was little more than a club of passionate underwater enthusiasts.

Yet there was a time before even those first dive centres made their marks upon the desert shoreline; a time when much of the Red Sea had only been explored underwater by the likes of Hans and Lotte Haas, Eugenie ‘Shark Lady’ Clarke and, perhaps its most famous visitor, Jacques-Yves Cousteau.

For much of the 1960s and early 1970s, scuba diving as a hobby was virtually unknown – it was mostly the preserve of ex-military personnel, wealthy enthusiasts

and marine scientists.

It was the latter that fired the interest of a young Egyptian boy named Adel Taher, the son of a close friend of Professor Dr Hamed Abdel Fattah Gohar, who ran the marine biological station in Hurghada.

During the school holidays in the summer of 1965, a nine-year-old Taher found himself visiting Dr Gohar’s laboratory, entranced – and saddened – by the marine life

kept in the lab’s specimen tanks, and learning all he could from the professor, his mentor.

Taher’s attention was also drawn to the brightly painted yellow scuba tank, which Dr Gohar used to collect his samples from the local reefs. The boy already had a deep fascination with the equipment from his love of TV shows such as Lloyd Bridges’ Sea Hunt, and Dr Gohar patiently explained to him how it worked.

An enthusiastic snorkeller, Taher assisted the professor by collecting samples from the local reefs, until one day he was asked to collect a sample of a particular species of coral that was too deep to reach. Disappointed, he reported his failure to the professor. ‘Take the tank,’ was his reply.

Thus began Dr Taher’s lifelong commitment to scuba diving. An introduction which today – as one of the world’s pre-eminent hyperbaric physicians, director of the Divers’ Alert Network (DAN) for Egypt, and director of the hyperbaric chamber in Sharm El Sheikh – he would most assuredly disapprove. Just the idea of a nine-year-old teaching himself to dive would surely horrify most divers, never mind the fact that he was using a tank so large it reached his knees, without a pressure gauge to monitor his air supply, and no training other than ‘Don’t hold your breath’.

‘Sometimes we’d go out diving, and we’d have only three tanks, but there were five or six people, so we would share our tanks’

Nevertheless, it was an introduction to diving that would help foster the early days of Red Sea scuba diving and – importantly – from a uniquely Egyptian perspective. Most divers who have spent some in Sharm will be familiar with the name ‘Dr Adel’. If you need to see a physician in Sharm, you see Dr Adel. If you need to see a diving physician elsewhere in Egypt, it’s likely they call Dr Adel.

The Deco Boys, a comedic band of musical dive instructors, borrowed three of Bob Dylan’s most famous chords to produce the hilarious tribute ‘Knockin’ on Adel’s Door’ (check it out on YouTube). His clinic in Sharm was (and still is) where every diving medical incident or emergency, which have been numerous, in such a busy resort, was sent.

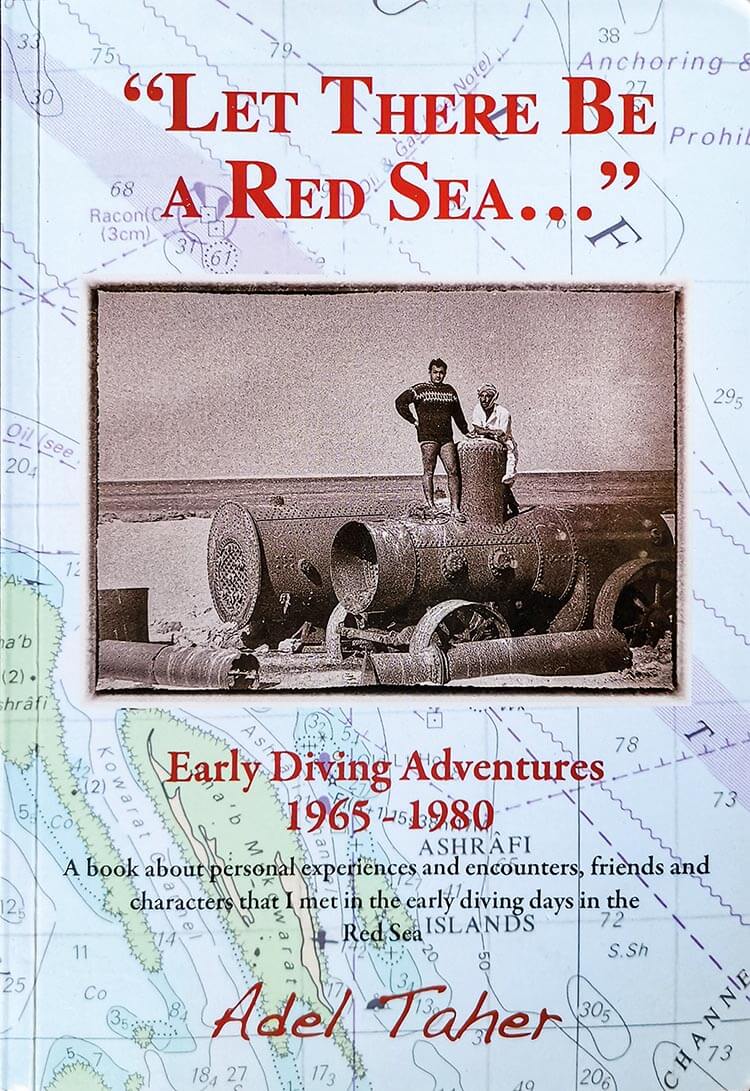

But very few of those divers and instructors – and even many long-term ‘Sharmers’ – know that the unassuming and avuncular Dr Adel Taher is also one of Egypt’s diving pioneers. Now, almost 60 years after his first dive, he has recorded his memoirs in a new book: Let There Be a Red Sea…, an account of his experience of diving during the 1970s, until he moved to Sharm El Sheikh in 1982.

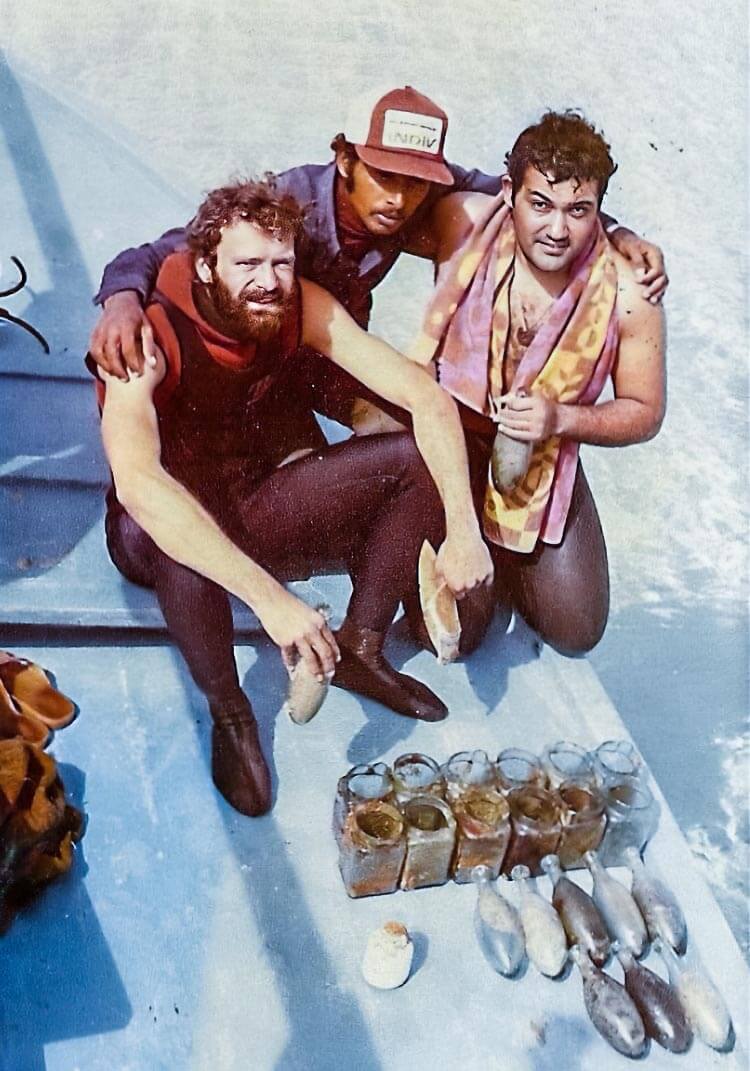

His first group of diving friends – which included Hani Wael Mansour Fahmy, Hani Khalil, Mounir Toueg, Khaled El Hosseiny, Farid Atiya, Ali Saad El Din, Youssef ‘Fox’ Esmat, Abd El Hamid Askar, Ayman Taher, Captain Hani El Meniawi and his wife Laurey; Captain El Shazly Moussa and his cousins, Ramadan and Ali; Amir Abou El Wafa, Captain Saleh Bayouk, and Taher’s future wife, Carolyn Ennis – were all almost entirely self-taught.

Equipment was purchased through Kyros Pascalis, a Greek trader in arms, ammunition, and scuba gear. They shared what funds they had in a communal kitty, and learned how to spearfish to provide food for their adventures.

‘We were young people,’ said Dr Adel – he will never be ‘Dr Taher’ to a Sharmer – ‘We were very eager to explore, but you have to keep in mind that we were not financially in the shape to do everything we wanted.

‘So we ended up putting a penny on a penny on a penny and even travelling to Europe to work, simply to make enough money to be able to rent the fishermen’s boats and go out and get the filters for the compressors and start collecting our own dive gear – and it was not easy.

‘Sometimes we’d go out diving, and we’d have only three tanks, but we were five or six people, so we would share our tanks,’ he said. ‘It would be known that you could dive on your tank to this depth for only twenty minutes because we need to keep air for others.

‘We shared almost everything, and later on we developed for our trips this idea of the cache commune, as they call it in French. Everybody puts in, say, fifty pounds, and for those who couldn’t put in fifty pounds, somebody would put one hundred pounds.

‘The ones who had more, supported the ones that had less, and the ones who had less worked hard and paid it off. It was a decent thing.’

It has to be remembered also that these adventures took place against a background of a regional armed conflict with Israel, which had seized the Sinai Peninsula during the 1967 Six-Day War, leading to a period of hostilities that was not resolved until a ceasefire was finally negotiated following the October War of 1973.

‘The financial situation got much, much worse after the war,’ said Dr Adel when we spoke. ‘Even food was scarce at times. I remember we used to stand in line to get some frozen chicken from the government.

‘But,’ he said, ever the optimist, ‘on the other hand, the rents for the boats went down. That was a good thing, for us.’

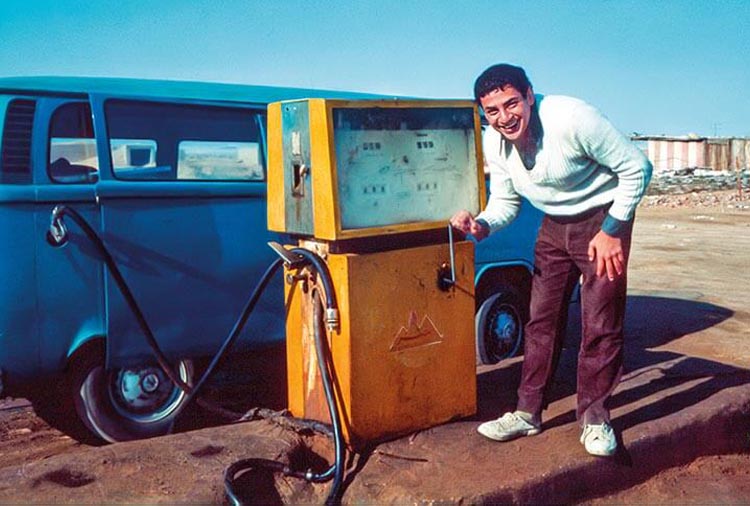

The privations involved in their adventures were not just financial. Travelling from Cairo to the Red Sea coast involved driving a car with a dinghy strapped to the roof and a compressor wedged in the trunk for up to 18 hours over more than 900km of roads – which were more holes than tarmac – and where refuelling involved the lengthy and physically exhausting process of drawing petrol from a mechanically operated pump with a hand crank.

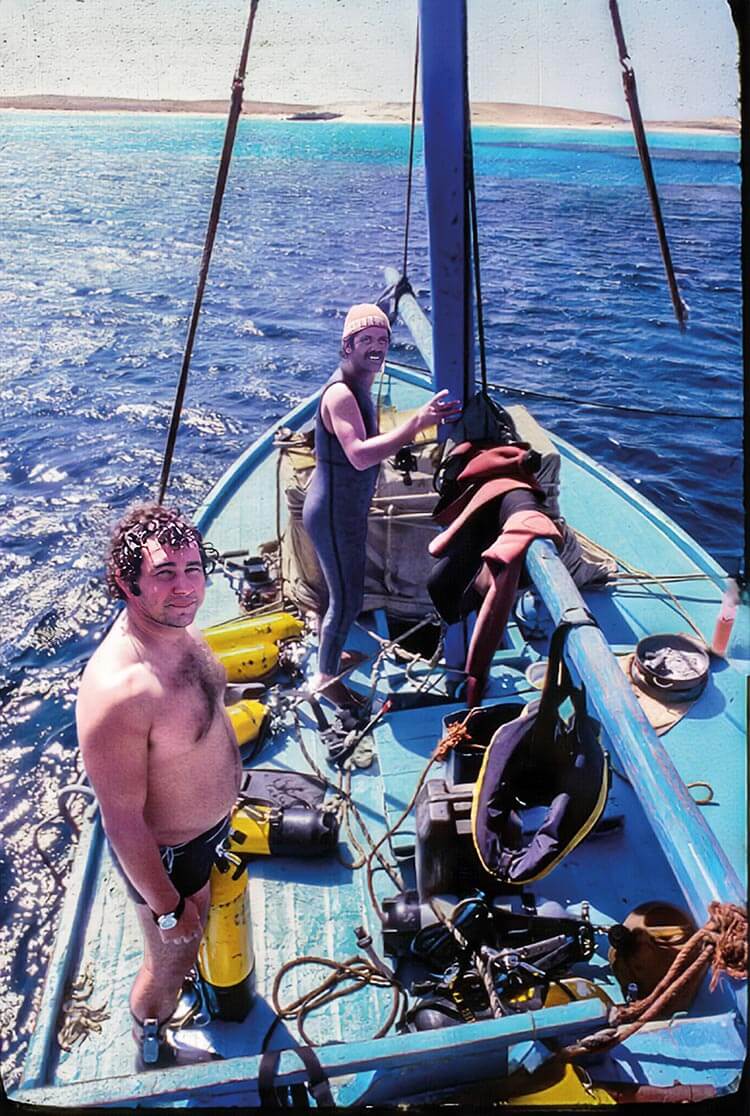

For longer voyages, they recruited the help of local fishers, who piloted their 9m-long ‘Gameyya’ fishing boats across water that can become spectacularly rough – a far cry from the modern three-deck dive boats and air-conditioned luxury liveaboards in use today. It is hard to imagine what these adventures must have been like, and it is not easy to understand just how significant they are to the history of Red Sea diving.

Together, Taher and his group were the first to dive Zabargad Island since Cousteau visited in 1956; they discovered the wreck of the Ulysses at Gubal Saghir and located two, perhaps three German submarines in the Mediterranean near Marsa Matruh.

In 1983, Taher was a student on the first PADI Instructor Trainer Course (ITC, later renamed Instructor Development Course, IDC) ever held in Egypt, thus becoming one of the first Egyptian dive instructors ever to be certified. He was also the first to dive the famous wreck of ‘Captain’s BMW’ at Yolanda reef, after the ship of the same name foundered there in 1980. ‘And we took spare parts out of it,’ he said, laughing!

The first PADI ITC in Egypt in 1983. Photographer Eric Hanauer is bottom left (Photo credit: Eric Hanauer)

Let Tere Be a Red Sea… is a collection of recollections placed in historical order, rather than a narrative-driven history of Egyptian Red Sea diving. It is beautifully written, and brings to light some of those first years of recreational Red Sea diving, plus some of the difficulties, comedic moments, near-misses and tragedies that Taher has experienced along the way.

It is also a reminder that time and development are not always beneficial, especially to the environment. ‘It was always a pleasure to dive on a reef where you don’t find a single fire coral broken,’ he said about those early days of diving. ‘Now, when you dive I look always at the bottom and on the sandy bottom you see broken fire coral, which is sad because now you see it even in the Ras Mohammed marine park.’

There is an innocence and naïveté to the stories; young men and women with a penchant for adventure but with no real knowledge of the dangers they were placing themselves into – not through any fault of their own, but because nobody had ever done it before.

History is a fickle subject, especially in an age where if it is not written down, it doesn’t last beyond the generation that lived it. Tragically, some of those who lived these adventures have since died – including Farid Atiya, the group’s photographer – and Taher feels that the time has come to honour their memories.

‘Times were different,’ he said. ‘People were different, and we were content with the basics and enjoyed every hour.

‘Many have passed away and their kids do not even know that their fathers were among a crazy bunch that started actually a sport in the Red Sea.

‘They were pioneers and I thought their names should be mentioned.’

Zabargad Island, Above and Below

Finally, a dream was starting to materialise. Images we had in our minds were starting to take a tangible shape; fish that we imagined we would find were swimming beneath us, and the elusive island was about to appear on the horizon

Making the crossing southeast, we soon could not see the mainland any more, and we were a tiny speck in the most beautiful ‘blue’ any sea in the world could boast.

I have travelled to many seas in the world, and some are grey, some are greenish-grey, and some have a tinge of brown. None have that eternal, clear, dark blue that characterises the Red Sea.

Suddenly, our sea conditions changed. The wind and the waves picked up, and our smooth crossing became quite rough. Waves rocked our boat, and our beautifully sounding engine started making strange sounds.

We finally saw the island around sunset and started approaching from the northwest, where an ancient rock quay could still be seen. It probably dated back to the time of Ptolemy I, and was built by slaves.

To reach the quay and throw anchor, we had to carefully navigate around several coral pinnacles that reached the surface. This took some time, and the sun set beyond the island and darkness started creeping slowly around us.

I wanted to be the first one to set foot on the island and jumped from the boat, and was trying to balance myself on the rocky pier. This proved to be quite difficult. The rocks were large and spiky with sharp edges, and it was painful to balance.

I realised it would be much easier if I walked on the reef. It was getting darker by the minute, and we were in a rush to unload and set up camp, and rest our tired bones and stiff muscles. So, I stepped onto the dark reef, which was covered by less than two feet of water.

The reef moved! Oh my God, it moved! The whole reef plateau moved under and around my foot as if my step had created a wave that was being propagated along the entire reef. I looked at the reef and could not breathe, I wanted to cry out loud, but nothing came out. I was terrified and could not move an inch – one foot on the rocky jetty and the other on that spooky reef.

Was the island haunted? Was I cursed because I dared disturb the suffering souls? The whole reef, seemingly covered in what looked like a dark-brown or blackish layer, had started to move as soon as my foot touched it. Surreal! I was shaking and could not utter a word. Indeed, this was paranormal.

Then, before screaming and making a fool of myself, I took a closer look and realised the whole reef was covered with dark spiny lobsters, one next to the other, like a carpet. They were so dense; one could easily have walked on them. In fact, I was standing with my right foot on the tail of a giant lobster. Unbelievable! I have never seen anything like that. Heaven!

I screamed out with joy, not fear, bent down and held the lobster with my hand, the proper way I had been taught, and waved to the gang on the boat. We will dine on lobsters tonight; what a grand welcome!

An hour later, we had had our fill of lobsters, which were humongous compared to what we were used to. For the following week, we ate lobster for breakfast, lunch, dinner and snacks. After that, we could not see or even smell lobsters for about a year.

We agreed to try to dive the island systematically and decided to start with the quay area. The depth was reasonable, five to 15 metres close to the boat and gradually sloping down to 22 metres, with many coral blocks and towering structures reaching up to a few metres below the surface and scattered all over the underwater terrain.

These mounds almost reaching the surface rendered sailing and navigation an utter nightmare, especially during low tide and big waves. The corals were pristine, mainly hard corals, with all the tips of the filigree of fire corals intact, not a single broken piece. The colours and shapes were a feast for the eye. We saw, our brains registered the images, and then somewhere, deep inside, feelings of admiration, reverence and utter respect developed. Mother Nature was rewarding us and allowing us a peek at a million-years-old, unaltered creation.

The size of some of the coral blocks indicated that they had been growing undisturbed for an unimaginable time. Untouched by fishing lines, pollution, or by plastic and wrapping material. Undisturbed by clumsy divers with their flapping fins, bad buoyancy and awkward movements breaking and crushing great table and elkhorn corals. We discovered to our amazement, that many species of hard corals we found had never been identified previously.

The following day we took the boat and sailed to the lagoon, looking first for a passage through the barrier reef that would allow us to squeeze our little boat into the turquoise lagoon; but we could not find any, so we set out to explore the narrow reef.

The bottom was clear beneath us, and we could estimate the depth to be around 12 to 17 metres of crystal-clear water. We got our gear ready and as I looked down there, I saw our first shark, quite large, probably a grey reef shark.

Ramadan Mousa decided to throw the boroussy, or the heavy anchor, to the bottom, when he realised we were going to spend some time on the island. As he did, I made sure it landed on sand and away from any reef formations, and followed it with my eyes as it hurtled down to the bottom.

I could not believe what else I saw: five or six sharks appeared from who knows where and rushed elegantly towards the slope and anchor. They quickly inspected it and dispersed, but remained in the area.

It is sometimes amazing how quickly one can change one’s mind! All of a sudden, I was not so eager to jump into the water. We discussed the situation and decided to ease ourselves into the water rather than jump in, and to see what happened. Farid, of course, had a big smile on his face – he was the photographer, and with this number of sharks in one dive, he was going to have a feast.

We slid into the water as planned, without creating unnecessary havoc and splashes. The sharks were inquisitive but did not dash towards us and took their time to watch and evaluate from a safe distance. Their movements were sometimes erratic and showed nervousness.

We were probably the first human beings they had laid eyes on. It must have been confusing for their brains to see creatures under the water causing so much noise, and blowing screens of bubbles rhythmically.

Within the first few minutes of our first dive on that magnificent reef, we realised we were experiencing very strange fish behaviour. None of the fish swam away when we approached them. Many came very close to check out these new creatures making that loud noise and bubbling away as they clumsily tried to move in that thick, dense medium called water.

The sharks also did not disappoint us. As time progressed, they too came in very close and several of them, mainly the silky sharks, wanted to touch our skin, to get a taste. Not all of us had wetsuits, which were very hard to get in Egypt in those days and cost a fortune to import. I was diving in shorts and a T-shirt.

They came in very close and several of them, mainly the silky sharks, wanted to touch our skin.

It was scary at the beginning, but we got used to it and for the remainder of the first dive and the dives that followed on the island, the sharks accompanied us. We respected them. On the other hand, they could not understand our presence in their environment and were perplexed that we did not swim away scared, as most sea creatures did when they approached them.

Now and then, they would try something to see how far they could get without us responding. That kept us alert. Carolyn decided to take with her a short, wooden stick with a makeshift lanyard, and it certainly helped in fending the sharks off without injuring them.

You want to avoid blood in the water around sharks – whether it is yours or theirs, the result is usually the same and can get messy!

It was one of those rare chances you get in life, when you could have studied the behaviour of sharks and their first response to divers in the water. Unfortunately, we did not have that analytical, scientific mind at the time, and we had no marine biologists accompanying us. You cannot have it all!

Extracted from Let There Be a Red Sea… by Dr Adel Taher.

The book is currently only available from the chamber in Sharm El Sheikh and – at the time of writing – the first print run has sold out. A second is in production and an Amazon Kindle release is expected. Stay tuned to our website for updates.