Renowned as one of the world’s best cold-water dives, Vancouver Island diving brings with it clear water, a great climate, miles of coastline – and massive marine life, including leviathans such as wolf eels, sea lions and the legendary giant Pacific octopus. Rob Bailey is your guide to Canada’s rugged island paradise

Words and photographs: Rob Bailey

The September morning sun shines high on the eastern horizon and there’s not a cloud in the sky. We’re miles from the nearest road and as far as the eye can see we are alone. This is our first dive on Browning Wall, off Canada’s Vancouver Island, and the anticipation is building as we put on our equipment.

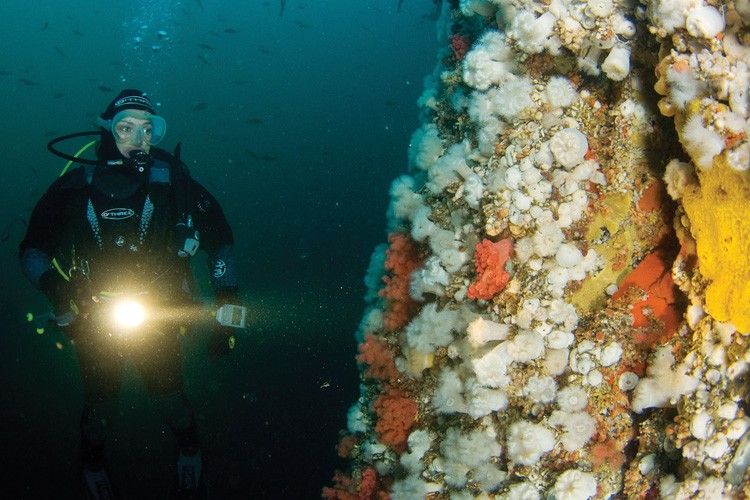

Armed with cameras, we break the mirror-calm surface and recognise immediately why the site is so special. It’s a vertical mosaic so colourful and so crowded with life that it rivals any tropical reef. The emerald-green waters, with visibility of 25m, are teeming with fish, and planktonic life ceaselessly drifts by. There’s so much to take in – and that’s before we get to the big stuff…

This area is renowned for being home to some of the largest invertebrate life on the planet. Sunflower starfish are a metre across here and plumose anemones reach that size in height. Orange peel nudibranchs can grow to 45cm in length, and there are reports of giant Pacific octopus with arm spans of up to a staggering 7m. Pausing for a second to take in the beauty, I realise that every square inch of space has life on it. So far, it has lived up to its reputation as the best temperate-water wall dive in the world.

Located at the far southwest corner of Canada, Vancouver Island is the largest island on the Pacific coast of North America, at nearly 300 miles in length and 50 miles at its widest point. The island has a mountainous spine that divides the glacial fjords of the wet, rugged west and the rolling hills, tree-covered islands and sheltered coves of the drier east. About half of the island’s population of 750,000 live in and around Victoria, the capital of British Columbia, at the southern tip. The remote north is a pristine wilderness of forests, lakes and snowy peaks.

We at Leamington & Warwick BSAC had been intending to visit Vancouver sland since 2007, and in September 2009 our plans finally came to fruition. Our party of 16 divers – comprising members of the club and of the Bristol Underwater Photography Group – embarked on a two-week trip encompassing the polar opposites of the island.

The first week would take us to Browning Pass, a stretch of water at the top of the island. The second half of the trip took us to the island’s south and to Ogden Point Breakwater in the harbour of downtown Victoria, a marine sanctuary and purportedly Canada’s most popular dive site. Although the island has many more dive possibilities, diving these two locations would be sufficient to see some of the island’s iconic creatures. And from a personal perspective, I particularly wanted to revisit Browning Pass, ten years after I was last there, to see if it was still as good as I remembered it.

Late one afternoon diving Vancouver Island at a site called Crocker Rock, bright sunshine and virtually no swell invited us onto the wreck of the SS Themis, an 82m wooden-hulled steamer that carried copper ore when it went down in Browning Pass in a gale in 1906. Today, the wreck is little more than scattered remains, with much of the wreckage resting inside a kelp forest. But the rockfish are plentiful and much larger here than on other sites, with resident lingcod approaching 1.5m long. Large rose anemones living on the debris added splashes of colour to the scene.

Our hopes of finding one of the resident wolf eels – at up to 2.5m long, the world’s largest blenny – were realised as we surveyed the wreckage trail. Following a stream of rising bubbles further out on the wreck, I saw that some of our group were already interacting with the inquisitive fish, whose size, compared with the much smaller Atlantic wolf-fish, is an eye-opener. After several shots were taken, we worked our way into the kelp forest, and were enchanted by the waning sunlight falling through the kelp and the schools of black rockfish in the background. After surfacing, one of the group declared the site to be among the best they had visited in more than 20 years of diving.

This part of the North American coast is home to some of the world’s fastest water, with currents approaching 15 knots in places. Queen Charlotte Sound, the body of water to the north of Vancouver Island, is an area of high biological productivity and diversity as a result of the abundant nutrients supplied by these currents.

Despite this, Browning Pass, located off the northeastern coast of the island, offers calm, sheltered waters, which helps to guarantee diving every day at one of one of several spots within a 15-minute boat ride of Clam Cove on Nigei Island, the location of Browning Pass Hideaway’s dive centre and cottages. The tides dictate the diving schedule, with two high and two low tides of varying height each day. We managed three dives a day over six days, and although the water temperature was a cool 9–11°C, the sun was shining so the group still found it comfortable and relaxing.

Heading out to the sites each day was every bit as awesome as the diving: on several occasions, the sky was graced with bald eagles, black-tailed deer grazed on the shore, and gangs of Steller sea lions made their presence known by leaping and spyhopping. Our host John de Boeck, the owner of the Hideaway, is undoubtedly one the most experienced boat captains on the island, and put in us into virtually current-free water on most dives.

The aforementioned Browning Wall is the star of the area – it is covered with red soft coral, sponges and an array of marine life. The wall reaches at least 30m above the water line and drops to over 60m at its deepest point. It’s not to be missed.

No matter where you travel, seeing the local ‘celebrity’ creatures is on everyone’s to-do list. Diving Vancouver Island was no exception, and the giant Pacific octopus, the subject of various anecdotes, stories and tall tales, topped the list. They can be seen on many sites and tend to venture out of their lairs when the tide is slack. At Browning Wall, we watched as one octopus put his arms around a large Puget Sound king crab and struggled to find a way in. As I tried to photograph the spectacle, a decorated warbonnet swam into frame. After about five minutes, the cephalopod, realising that the crab was impenetrable and not in the least worried about the would-be predator, abandoned his designs on dinner, leaving us to reflect on a first-class encounter.

After a week in the north, we moved on to the southern leg of our trip and to Ogden Point Breakwater, a 400m-long concrete structure built in 1916 to protect the Victoria harbour from the waves of the Juan de Fuca Strait. The breakwater is marked with five dive flags painted on the lower tiers. Each flag denotes different habitats, and a map in the shop at Ogden Point Dive Center explains what you might see at each station. They’re all easily accessible, but depending on what you want to see, be prepared for a bit of walk: the last marker is near the end of the breakwater, and is quite a journey with full kit. Luckily, the shop has a few trolleys available to ease the load.

The breakwater is an ideal place to tick off all those creatures you want to see. We spent our two dives checking out the resident wolf eels, which are hard to resist when they’re around. You can also spot octopus, ratfish, skate, a decent population of good-sized lingcod, kelp forests, a variety of jellyfish, and all of the usual macro subjects, such as grunt, sailfin and scalyhead sculpin, at depths of 8–35m – not bad for a downtown site.

Just a few miles southwest of the harbour is Race Rocks – a small rocky islet and ecological reserve that the locals say is the best site in the area. Ogden Point Dive Center has a speedy, custom-built aluminium boat specifically to ferry divers to this site, which can be subject to high currents. Erin Bradley, the centre’s owner, was an excellent host for the day – friendly, helpful and organised.

While there’s a kelp forest and an excellent 34m wall dive here, the main attractions are the Steller and California sea lions that bask in great numbers on the rock. The size and speed of these great pinnipeds is daunting at first, with the Steller males reaching lengths of 3.5m and weighing more than a tonne. They seemed more wary of humans than British grey seals, but came in from time to time for flybys. When we poked our heads out at the surface after the dive, we were confronted by a roaring Steller ostensibly claiming his territorial rights.

I was relieved to see that after a decade away, the marine life of Vancouver Island was just as abundant – or even more so – than I remember it. Luckily, calm water and sunshine seemed to follow us wherever we went, and it’s safe to say that the entire group took away some amazing memories. We’re already planning another trip back.

NEED TO KNOW

Note: this article was first published in 2014; prices have been updated for 2023 but may vary substantially from those listed.

Getting there

Air Canada (www.aircanada.com) offers direct daily flights from Heathrow to Vancouver on the mainland. Prices vary depending on season, but direct economy class return flights can be purchased for around £1,000 for a flight, depending on the time of year. Flight times are about nine and a half hours.

We travelled from the mainland to Vancouver Island by ferry (www.bcferries.com) – we took our hire car on board, but foot passengers and coaches can also travel. Sailing times from Horseshoe Bay in Vancouver to the island are one and a half to two hours. Adult one-way fares cost C$19.45 for a passenger on foot, while cars cost from C$93.35.

When to go

The best times for diving Vancouver Island are late March to early May, or late August to October, mostly owing to calm weather and to avoid the summer plankton bloom. The average water temperature along the coast is 8–12°C. The climate here is the mildest in Canada, with coastal temperatures reaching more than 30°C in summer and rarely falling below zero in winter.

What to take

Standard UK dive equipment is perfect – bring a drysuit if you want be comfortable. Topside, summers are warm enough for shorts, T-shirts and dresses, but pack a jumper, trousers and a light jacket for cooler evenings and sudden changes in the weather. Be sure to take a raincoat, umbrella and scarf for blustery days during spring and autumn.

Accommodation

Update 2023: Browning Pass Hideaway (www.vancouverislanddive.com) where Rob stayed during his trip is unfortunately no longer operating. Local divers have recommended UB Diving (www.ubdiving.com) as an alternative for dive trips through the Summer and Autumn in Port Hardy. Quarterdeck Resort (www.quarterdeckresort.net) is located on the docks for an easy pickup by boat, with prices starting around CA$109. Helm’s Inn (www.helmsinn.com) was recommended at the time as an excellent hotel five minutes from Ogden Point – prices currently start from C$130 a night.

Dive centres

Tanks, weights and airfills at Browning Pass Hideaway are included in the package cost; nitrox is also available. For a comprehensive list of dive centres, dive charters and dive site descriptions around Vancouver and Vancouver Island, head to www.scubabc.ca

What you might find

Ever wondered what it might be like to get hugged by an octopus? Check out ScubaBC’s YouTube channel for a preview of some of the wildlife you’re likely to encounter!