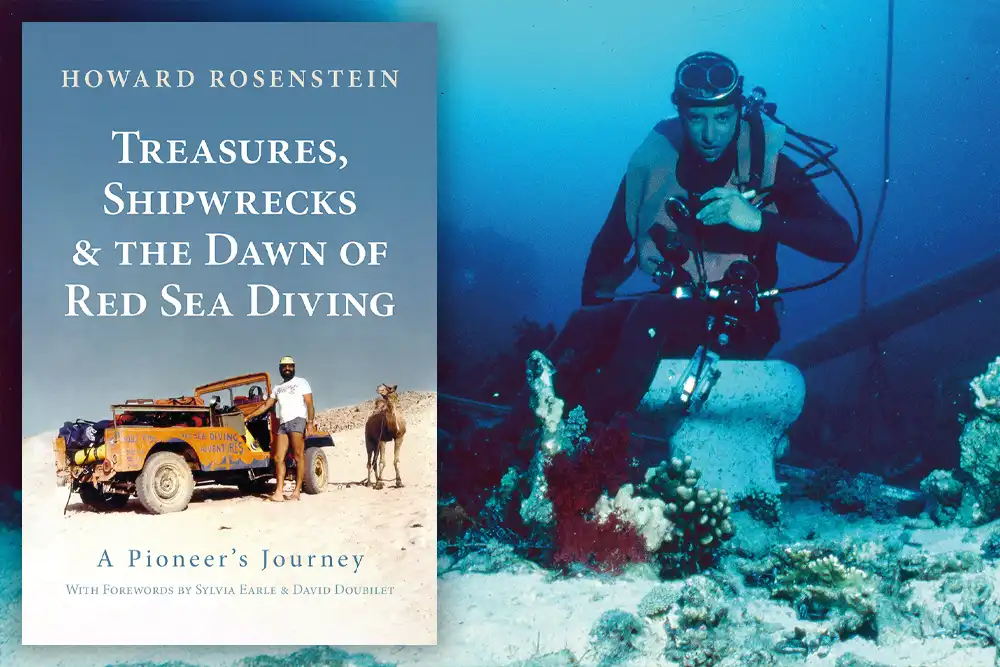

An extract from the book Treasures, Shipwrecks And The Dawn Of Red Sea Diving, in which Red Sea scuba diving pioneer Howard Rosenstein details what happened the day one of Egypt’s most famous wrecks struck a Ras Mohammed Reef

Introduction by Mark 'Crowley' Russell

IN THE BEGINNING…

In 1966, a 19-year-old student by the name of Howard Rosenstein travelled from Los Angeles to Israel during a summer break from college, and on a whim decided to try snorkelling.

Thus began an adventure that would help kick-start the growth of what is, today, one of Egypt’s largest tourism industries.

Captivated by the beauty of the underwater world, in 1970 – just six months after getting his basic NAUI certification – he started a dive operation on Israel’s Mediterranean coast, later expanding it to Nuweiba on the Sinai Peninsula before moving to Sharm El Sheikh, an area otherwise inhabited only by seasonal Bedouin encampments, and the site of a UN Peacekeeping base.

By 1974 he was hosting National Geographic photographer David Doubilet and his wife Anne, together with Eugenie ‘Shark Lady’ Clark. Their resulting September 1975 cover story highlighted Ras Mohammed as a wonder of the scuba diving world; a place for which Rosenstein would later engage in ‘diving diplomacy’ with the Egyptian authorities to persuade the government to designate the reefs a protected area – which it eventually did.

As a pioneer of Red Sea diving, Rosenstein was one of the first people to dive at sites that many of us know and love today. He was part of a team that discovered the wreck of Dunraven, and the first person to dive the wreck of Jolanda (it really is a J, not a Y!) when it struck Shark Reef in 1980.

In this extract from his recently published book, Treasures, Shipwrecks And The Dawn Of Red Sea Diving: A Pioneer’s Journey, (Check out Mark ‘Crowley’ Russell’s review here) Rosenstein details the story of how the Jolanda crisis helped persuade the Egyptian authorities to grant dive tourists access to Ras Mohammed and the newly named Shark and Jolanda Reef which – with its coral now interspersed with toilets and the wreckage of a BMW that, contrary to popular belief, was not the captain’s – would become one of the most popular dive sites in the world.

A DISASTER IN THE MAKING

Matters went from bad to worse on 1 April, 1980, when a Cypriot coastal freighter, the Jolanda, went aground at Ras Mohammed. The Israeli Navy tipped me off on the morning of the accident.

Standing in my front yard, I saw the stranded ship through my binoculars. I was anxious to get our dive team there to survey the damage and assess how it could be contained, but we first needed permission from the Egyptian authorities.

I called my friend and scuba diving student Samuel W Lewis, the American ambassador to Israel. Whenever he could, Sam – as he asked us to call him – would break away from his responsibilities to dive with us in Sharm El Sheikh.

In response to my request for help, he contacted the US Embassy in Cairo. Within twenty-four hours, Egypt gave us the go-ahead. I gathered my team members and took a dive boat to the scene the next morning.

Reefs are built by colonies of soft and hard corals so fragile that they can break at the swipe of a diver’s fin. Launched in 1964, Jolanda was seventy-five metres long, eleven metres wide – a 1,153-ton freight ship complete with cargo – and it was wedged atop the northern coral island at Ras Mohammed’s Shark Reef.

Its captain compounded the damage when he tried to dislodge the vessel at high tide. Yet more corals were destroyed when the ship dropped its large anchor on the shallow sea bed. Jolanda (pronounced Yolanda) came to rest on her port side in the shallows, but precariously positioned above a steep drop-off into the abyss.

A bizarre array of cargo was strewn about the seabed: from containers filled with industrial plastic sheeting, to porcelain toilets, to a new BMW stuck head-down on the reef.

When we arrived, a salvage vessel, the Montagne, had already dropped anchor atop a beautiful coral head that must

have taken centuries to reach its size and majesty. Salvage operators are paid based on what they retrieve, a ‘no cure, no pay’ agreement. As they let loose their chains and ropes, reef preservation is the furthest thing from their minds.

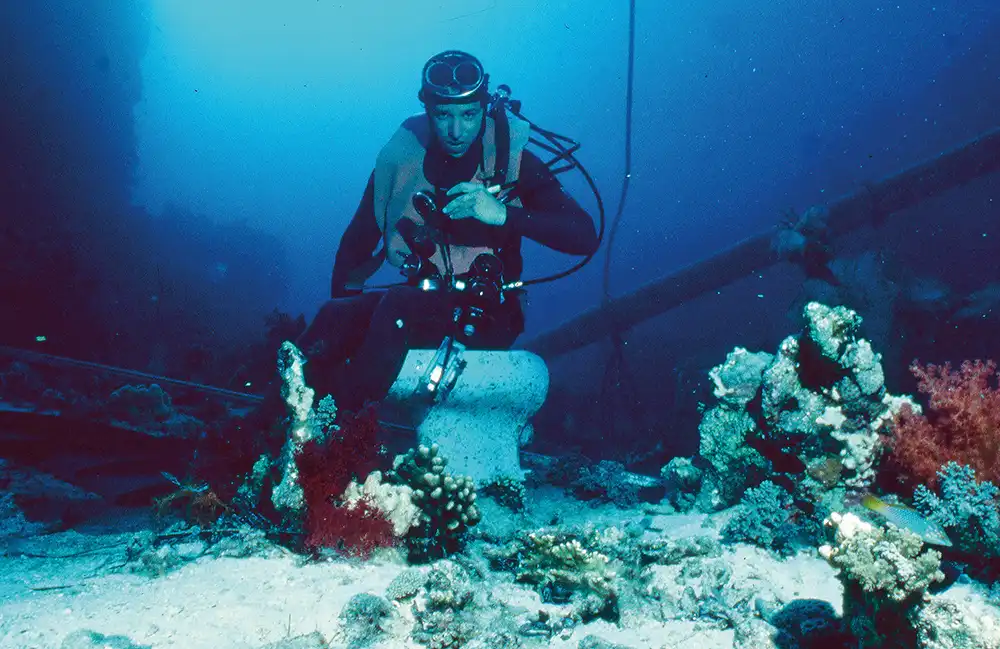

I photographed the scene above and below water, documenting the damage to the reef. Back at the dive centre, I notified the American Embassy in Tel Aviv about the disaster in the making. My mission shifted from getting dive access to Ras Mohammed, to saving the natural wonder.

Top US diplomats swung into action – Ambassador Lewis in Tel Aviv, Ambassador Alfred ‘Roy’ Atherton in Cairo and Ambassador in Jordan, Nick Veliotes. Egypt halted the salvage operation within days.

The Swedish captain of the Montagne, a huge guy, was angered by our interference, to the point of threatening my life. I first encountered him when I came up from my initial dive. Towering over me, in an inflatable boat, he asked me what I was doing on his wreck.

When he revved his outboard engine ominously in my direction, I quickly dove back down and navigated at depth toward the safety of our boat on the other side of the reef. At one point, the captain warned me of physical harm if I returned to the wreck site.

After the Egyptian authorities expelled him from the Jolanda wreck site, the Montagne’s captain decided to see what he could salvage from the nearby Dunraven, the century-old sunken wreck we had discovered three years before.

Leaving the Montagne anchored above, he dived into the wreck, never to be seen again.

Ironically, the Israeli and Egyptian authorities enlisted me to search for his body just days after he had threatened my life.

I combed Dunraven’s maze of silt-filled passageways, cabins, communal areas and cargo holds, to no avail. Perhaps the captain had become stuck trying to squeeze through a narrow passage. Another possibility is that he had become disoriented in the upside-down ship and had run out of air, trying to find his way out.

Over the next six years, Ras Mohammed absorbed the Jolanda, which essentially became an appendage to the reef that sank her. Coral colonies attached themselves to every available space on the submerged part of the wreck. Then, in 1986, a fierce storm dislodged the ship from its shallow perch, sending it 150 metres down to the base of Ras Mohammed.

The wreck was not accessed again until technical divers reached it in 2005. Among the remnants in the shallows are a few of the toilets, which still attract divers eager to pose for underwater photos on the coral-encrusted thrones.

Once the Jolanda crisis was resolved, Egypt reimposed its restrictions on Ras Mohammed and we resumed our fight to have them lifted. We again turned to the good offices of ambassadors Lewis and Atherton.

Prodded by the American diplomats, the Egyptians announced on 15 May that we could have sea, though not land, access to Ras Mohammed – and even that was restricted to the ten or so dive boats based in Sharm, half of which belonged to our Red Sea Divers fleet.

Instead of being able to come and go as effortlessly as we had done in the past, we had to present a list of crew and guests, along with their passports, to an Israeli official in Sharm each day by a certain hour.

The official would then drive to the temporary border at Ras Mohammed, where a tent had been set up for him to hand over the documents to his Egyptian counterpart. After reviewing the documents and stamping the passenger list, the Egyptians would issue one-day permits for diving the next day.

The Egyptian officials had a famous expression ‘No problems, only procedures’. Sometimes these procedures would mean no diving that day.

Although the process was cumbersome, it marked the first time that I knew that Israelis and Egyptians on either side of the border engaged in problem-solving as neighbours rather than enemies.

This article is an excerpt from Treasures, Shipwrecks and the Dawn of Red Sea Diving: A Pioneer’s Journey by Howard Rosenstein. Available from divedup.com in the UK (£30), olympusdive.com in the US ($46), and other online retailers.

Paperback

Hardback

More great reads from our magazine

- ‘Toxic Trumps’ – venomous sea creatures and how to treat their stings

- Where Oceans Meet – the amazing biodiversity of Cornwall

- Wild Edges – an interview with photographer Rebecca Douglas

- Scuba diving Derawan – the other side of the Sulawesi Sea

- Fire Alert – Improving liveaboard fire safety for divers