By Max James

False Bay in South Africa used to be one of the few places on the planet that divers safely protected by cages could reliably encounter great white sharks.

Along with Guadalupe Island off Mexico’s west coast and around Port Lincoln in South Australia, False Bay developed a thriving shark diving tourist trade.

But in recent years the sharks have stopped turning up to feast on the still plentiful fur seals in the vast sandy bay just east of the Cape of Good Hope and Cape town. As many as 500 great whites sharks were estimated to hunt in the bay.

In 2017 the cage dive operations reported a dramatic drop in sightings around False Bay and Gansbaii.

From 2010 to 2016, white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias) were sighted in False Bay an average of 205 times each year, according to conservation and research organization Shark Spotters. In 2018, the sharks were seen just 50 times; and in 2019, none. In January 2020, the first great white shark in 20 months was seen in False Bay.

‘I’ve spent my entire life in the field watching these animals on a daily basis,’ local cage dive operator and wildlife photographer Chris Fallows says.

‘When the waters go quiet, both above and below the surface, and these predators are not there, it sounds huge alarm bells.’

Scientists are baffled.

‘The reality is that we have way more theories than we have facts to support them at the moment,’ says marine biologist Alison Kock, of South African National Parks who has been researching white sharks in South Africa since 1998.

The first problem is understanding the size of the great white shark population around the whole of South Africa. Recent research on the genetics of great white sharks in the area suggests that there is just a single population and individuals roam from feeding site to feeding site.

However, the same research also indicates that the population may be as small as 500 with a study in 2009 to 2011 suggesting that this may only include 300 breeders. It is thought you need at least 500 breeders in a great white shark population for it to be viable long-term.

Sara Andreotti of Stellenbosch University said: ‘So our population was in real trouble already.’

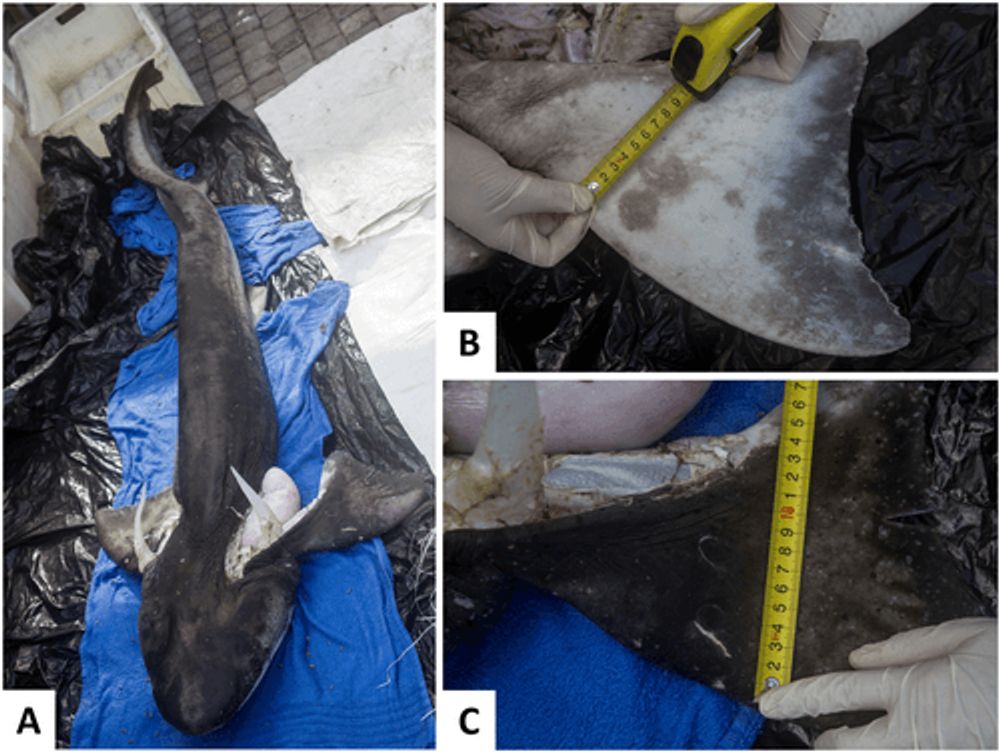

In 2017 a dramatic development caught people’s attention. Reports of great white sharks and sevengill sharks (Notorynchus cepedianus) found with their livers ripped out started to surface. Orcas are the only animals known to hunt in this highly effective way – the liver, which can weight up to a third of the total of a great white shark, is highly nutritious, being rich in fat.

A pair of orcas known as Port and Starboard were first spotted in False Bay in 2015. Another pod arrived at the end of last year.

A study partly written by Kock established that orcas have been responsible for the attacks and great whites and sevengill sharks in the area and noted that similar predation by orcas had been observed in the North Pacific. The report warns: ‘Both sevengill sharks and white sharks play an important role as apex predators in the ecosystems they inhabit. A reduction in their numbers due to direct predation from killer whales, combined with their prolonged absence from traditional aggregation sites, is predicted to have cascading effects throughout entire coastal ecosystems.’

However, while orca predation may have played some part in the disappearance of the great whites in the area, many fear that it is only part of the story.

Fallows, who has been putting researchers and film-makers in the water with sharks for nearly 30 years and has taken some iconic photographs himself of great whites leaping into the air with fur seals in their mouths, argues that Port and Starboard may have had some impact but they cannot explain the complete disappearance of what had been an apex predator for so long in the area.

He believes the culprit to be what is known as demersal longline fish where bottom-dwelling species such as gummy and school sharks are targetted with hundred of kilometres of lines with thousands upon thousands of baited hooks. These small sharks account for 60 per cent of the diet of great white sharks and are a particularly important food for juveniles. The small sharks are sold to Australia where they are popular in the fish and chip market and known as ‘flake’.

While great whites are protected in South African waters, their prey isn’t. South African shark scientist Enrico Gennari has been working with Fallows to improve the monitoring of the longline industry. They have footage which shows longline vessels illegally fishing in marine protected areas and even the landing endangered hammerhead sharks.

Fallows says the fishery is ‘destroying one of the world’s great marine ecosystems, and all for a plate of fish and chips!’

However, other researchers are more cautious about the link. One study noted that while great white sightings have plummeted in the Western Cape, they have spiked in the Eastern Cape where there is even more longline fishing.

Kock says: ‘You have to be careful, because you can have unintended consequences … for people’s livelihoods. It’s really important, particularly for people in the decision-making sphere, to have evidence-based information, so that they can make the right decision. And at the moment, in terms of the white sharks disappearing, that needs a lot more work.’