Hammerhead sharks are one of the wonders of the ocean. With their uniquely shaped heads, rising up from the deep, often in vast, mysterious schools, they are at the top of every diver’s wishlist. Here’s a rundown of what facts are known about hammerheads, where to find them and the threats they face

Hammerhead sharks are one of the smallest shark families, with two genera and nine described species. They are also the most threatened family of sharks with more than half of the species on the verge of extinction. Predominantly living on or near continental shelves has exposed them to extensive overfishing and their nursery habitat of mangrove forest have been significantly depleted in recent years. They are one of the most common victims of shark finning. Since updating this article from when it was first published two years ago, three more species have been placed on the ICUN Red List as being critically endangered.

However, divers can still regularly see and photograph them. Around the isolated seamounts of the Eastern Tropical Pacific vast schools of scalloped hammerheads gather during the day. In The Bahamas, great hammerheads are one of the main attractions for numerous liveaboard operators.

At COP26 it was announced that Costa Rica, Columbia, Ecuador and Panama have joined forces to vastly extend the marine protection zones around isolated islands such as Cocos, Malpelo and the Galápago into a vast no-fishing area protecting key migratory routes. These iconic sharks are seen as key species in the battle to conserve and protect our oceans.

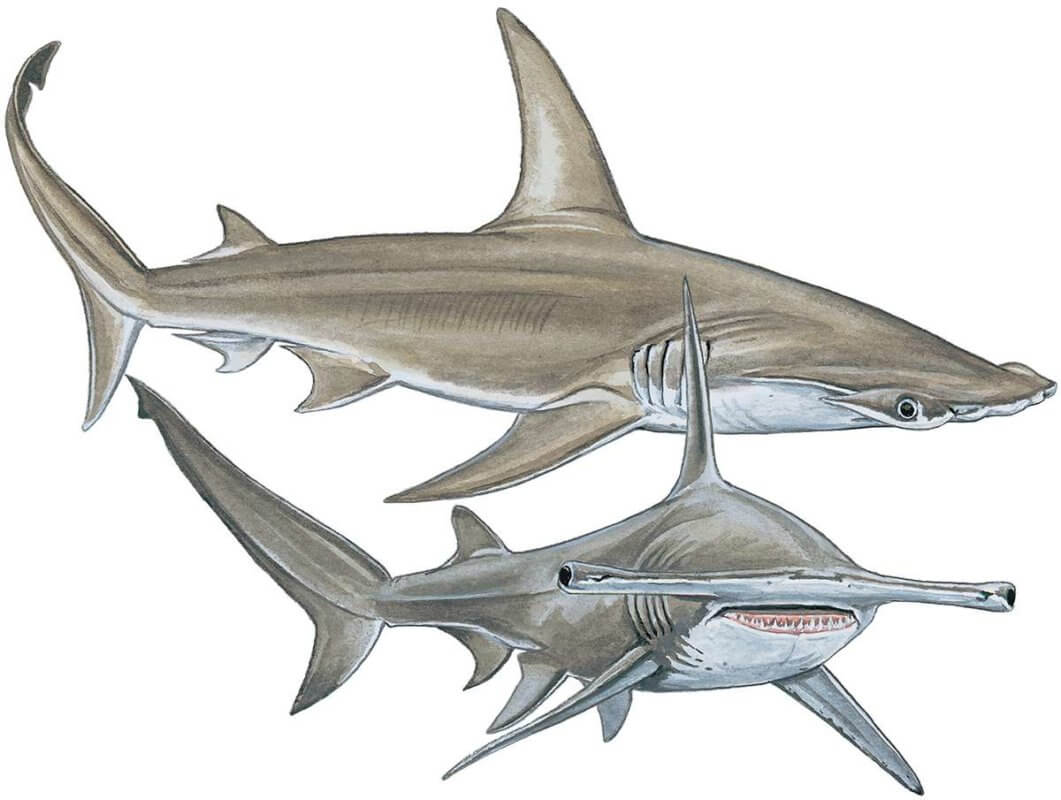

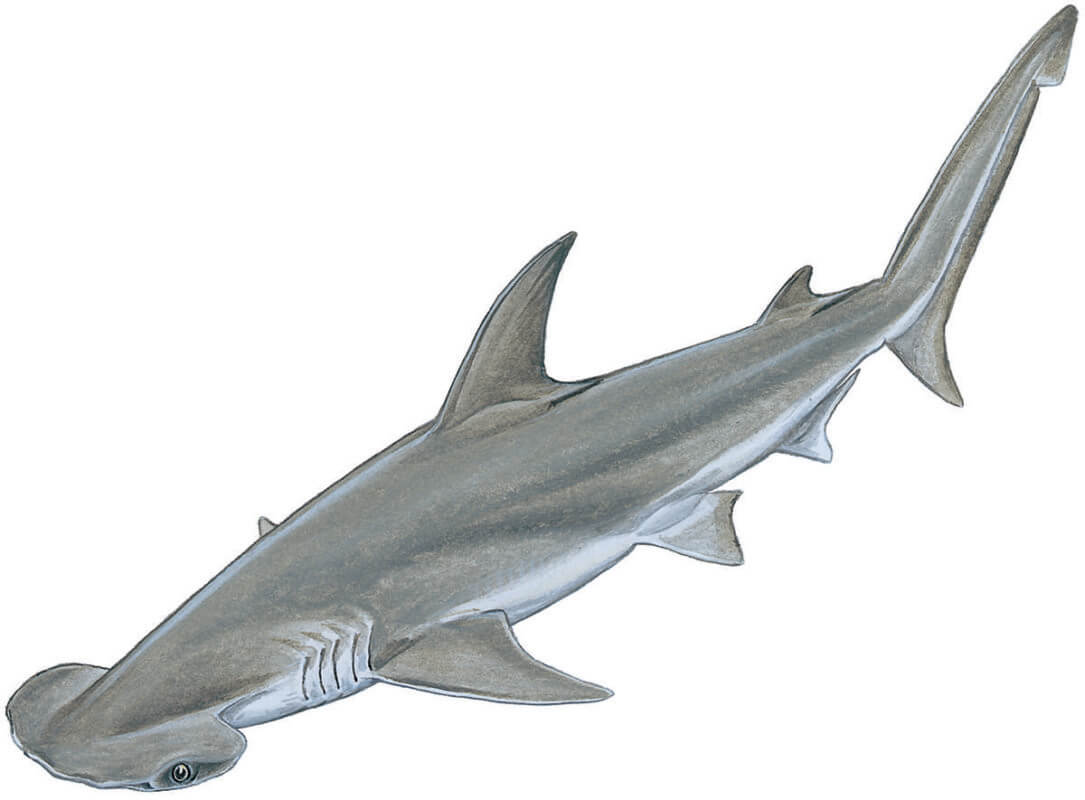

Great hammerhead (Sphyrna mokarran)

True to its name, the great hammerhead is the largest of the hammerhead sharks. They can grow to a maximum length of around six metres (the largest on record is 6.6m) and specimens more than 4m long are not uncommon. They tend to be solitary swimmers and are found in tropical waters worldwide. They often frequent coastal areas and are seen around coral reefs and atoll passes and lagoons. They are also seen far offshore. However, little is known about their pelagic and migratory behaviours.

They can be identified by their large hammer, or cephalofoil, which has a dent in its middle and they have a huge dorsal fin. One of their favourite prey items is stingray, though they eat a variety of other marine life including fish and crustaceans. They have litters of up to 50 pups at a time.

The Bahamas Banks is one of the best places to dive and photograph them with many operators offering special great hammerhead trips. They are also regularly seen at Coiba Island in Panama.

IUCN Status: Critically Endangered

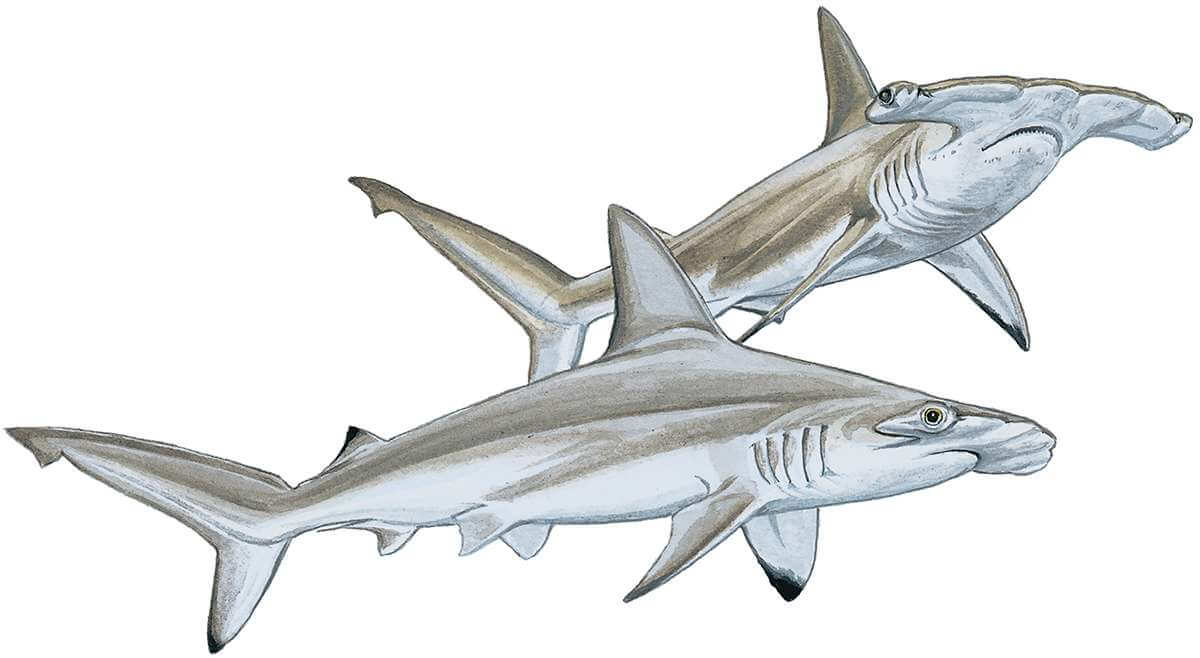

Scalloped hammerhead (Sphyrna lewini)

This relatively large hammerhead shark can grow to three metres in length and is recognisable by the notches in its hammer, which resemble the shape of a scallop shell. These sharks sometimes venture into estuaries and are found in warm temperate and tropical waters across the globe.

Young scalloped hammerhead sharks are known to use estuarine areas around Fiji during their early years. Considered to be endangered throughout their global distribution, the recent discovery of these aggregation areas is important in helping ensure the survival of these sharks.

Vast schools dominated by mature females patrol seamounts such as Cocos and Malpelo in the Eastern Pacific during the day and at night they disperse either alone or into small groups to hunt. Smaller, but equally, impressive schools are also regularly seen rising from cold water in the Red Sea at sites such as Brothers Islands and Tiran. Likewise, schools of scalloped hammerheads are regularly spotted riding the thermoclines in the Maldives, Indonesia, PNG and French Polynesia.

IUCN Status: Critically Endangered

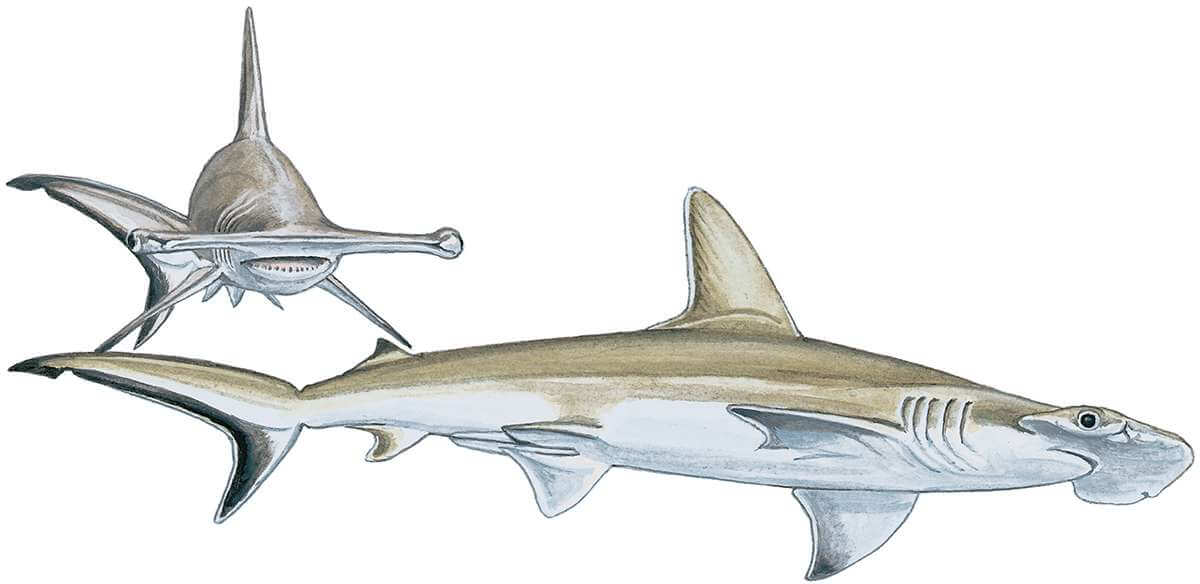

Smooth hammerhead (Sphyrna zygaena)

The smooth hammerhead doesn’t have an indentation in the centre of its hammer, giving it a smooth appearance, and these sharks are more tolerant of cooler waters than other hammerheads. They are found in temperate and warmer waters around the globe and they migrate to the poles during the summer to stay cool. They are the second-largest hammerhead shark after the great hammerhead and mature females can be as long as 4m. They feed on bony fishes – but will also feed on other sharks and rays. They stay closer to the ocean surface than scalloped and great hammerheads and prefer to spend time in bays and estuaries. As a result, smooth hammerheads have been heavily overfished.

IUCN Status: Vulnerable

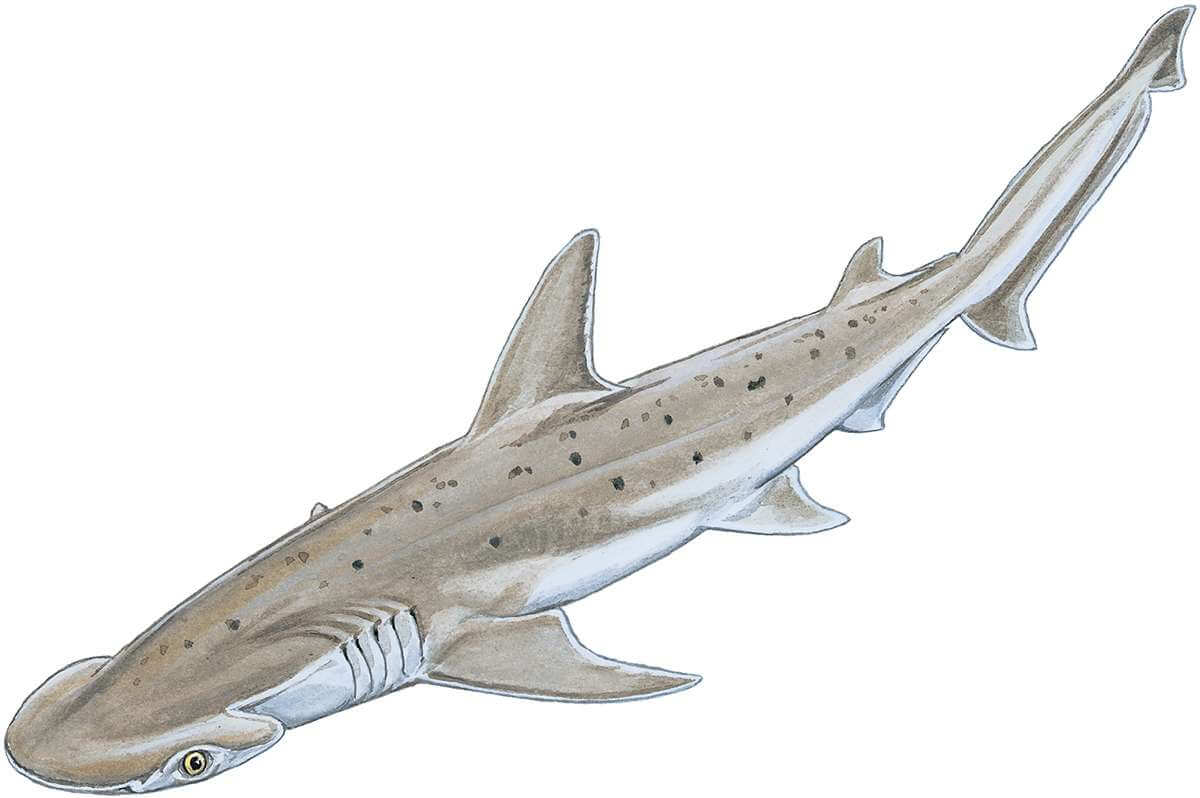

Winghead shark (Eusphyra blochii)

This small species of hammerhead, growing up to two metres in length, has a very large hammer as wide as 50 per cent of the shark’s length. They are found in tropical waters of the central and western Indo-Pacific and the Persian Gulf. They mostly feed on bony fishes. Pregnant females have been observed fighting each other aggressively and they have litters of up to 25 pups.

IUCN Status: Endangered

Bonnethead (Sphyrna tiburo)

This small and active hammerhead shark has a distinctive rounded head and is sometimes called the shovelhead. Males and females of this species have differently shaped heads, which is unique to this hammerhead species. The adult females have broad round heads, whereas males have a distinctive bulge in the middle of the hammer.

Most other species of hammerhead control their vertical movements in the water using their cephalofoils, rather than their pectoral fins, however, the bonnethead’s smaller head means it is much less effective at controlling the shark’s pitch, and so it must rely on its pectoral fins to do so.

Bonnetheads have comparatively much larger pectoral fins as a result, and are the only species of hammerhead to use their pectoral fins for swimming.

Females grow to 95cm, males to around 85cm.

They were once abundant on both the Pacific and Atlantic coasts from Rhode Island to Brazil and California to Peru. However, extensive overfishing has left them extremely rare across most of their range.

IUCN Status: Endangered

Scalloped bonnethead (Sphyrna corona)

This is a rare species of shark, relatively unknown, and sometimes called the crown shark or mallethead shark. It is found in the eastern Pacific Ocean and has a limited range from Mexico to Peru. These sharks spend their time inshore, sometimes visiting estuaries and mangroves, and feed on fish and crustaceans.

Females mature to nearly a metre in length, males are slightly smaller. They have a distinctive rounded head similar to the bonnethead shark. They only have two pups per litter, which are born 23cm in length.

Extensive artisanal and commercial fishing have devastated stocks in recent years.

IUCN Status: Critically Endangered

Scoophead (Sphyrna media)

The scoophead is another species of hammerhead that few people know about and is found in tropical waters in the Western Atlantic and Eastern Pacific oceans. It is slightly larger than the scalloped bonnethead but at first glance, they appear similar. The scoophead shark has a shorter snout and broad arched mouth.

This shark can be found living alongside bonnethead and smalleye hammerheads off the coast of Trinidad, where it feeds on octopus, smaller sharks, squid and flounders. Little is known about this species of sharks, but it is caught by fisheries throughout its range and it has suffered from the destruction of its mangrove forest habitat.

IUCN Status: Critically Endangered

Smalleye hammerhead (Sphyrna tudes)

Smalleye hammerheads have a unique bright gold colour on their heads and parts of their body and are sometimes called golden hammerheads or curry sharks. It is thought the colouration comes from pigment in the shrimps that juvenile smallhead sharks eat and from the sea catfish that adults eat. This distinctive colour may help camouflage them in the muddy habitats they prefer, making it difficult for larger predators to find them.

Females grow to 114cm and males to as much as 90cm.

They are commonly found in shallow waters off Venezuela to Uruguay and have litters of up to 19 pups each year. They are caught by fisheries throughout their limited range and their numbers are rapidly declining, making them vulnerable to extinction.

IUCN Status: Critically Endangered

Carolina hammerhead (Sphyrna gilberti)

The first specimen of the Carolina hammerhead to have been recorded was in 1967, however, it wasn’t formally described as a separate species until 2013. Its appearance is almost identical to the scalloped hammerhead but the Carolina hammerhead has 10 fewer vertebrae and is genetically distinct. Little research has been conducted into this shark and therefore there is no current data available on the conservation status of this species.