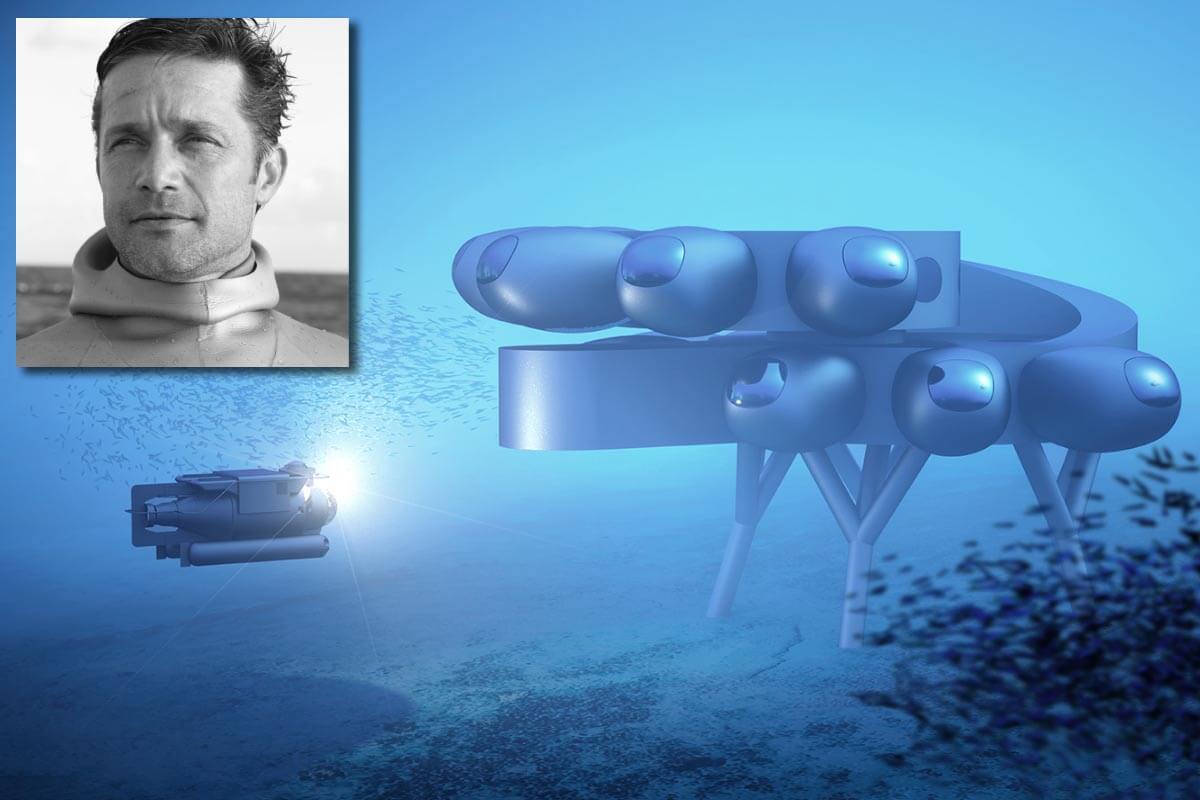

Fabien Cousteau wants to inspire the world with a futuristic underwater habitat, known as Proteus, scheduled to come online off the shores of Curaçao in 2026

While the world watches the jockeying of billionaires trying to conquer space, a far smaller project with a fraction of the Musk/Bezos/ Branson exploration budgets is quietly going about its business.

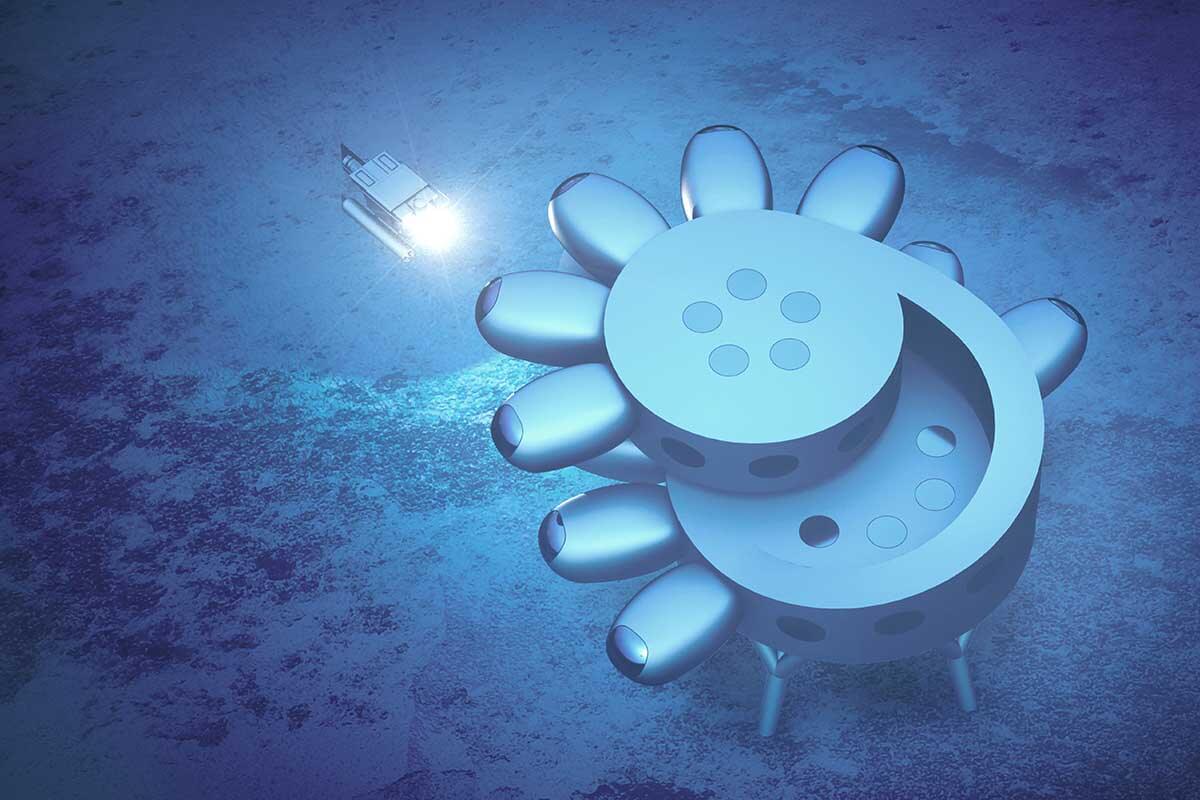

Project Proteus is taking shape and will probably have a far more profound impact on the future of this planet than the dreams of Mars missions. It is a ‘space station’ for the final frontier that actually matters: a habitat for humans to live, study and work underwater.

As its founder and driving force, film-maker and marine campaigner, Fabien Cousteau, declares: ‘If we don’t understand and learn how to protect the underwater world, we will have nothing. Our oceans are what keep us alive, and for too long we have debased and degraded them.’

Following in the venerated tradition of his grandfather (Jacques) and father (Jean Michel), 54-year- old Fabien is a committed and articulate advocate for ocean exploration. After spending 31 days in 2014 underwater in the Aquarius marine habitat, nine miles off the coast of Florida, he decided it was time to build and run a state-of-the-art underwater base to help bring humanity closer to the fundamental issues facing our oceans and, therefore, our planet.

Cousteau hopes that Proteus will be a hi-tech, carbon-neutral research station. He also wants it to be a focal point for a global campaign to raise awareness of the plight of the oceans and how our future is inextricably intertwined with their conservation. As he points out with passion, without healthy oceans there is no life on this planet.

The modular, flexible design, will be home for 12 scientists, engineers and researchers to live and work underwater. At a squeeze, the launch incarnation, which is due to welcome its first aquanauts in 2026, will have space for 18 people at any one time.

The main living spaces will be 20 metres under the surface just off the northeast coast of the Caribbean island of Curaçao. Last year, Fabien and his team completed a detailed survey of the one-kilometre-square site and, for good measure, also provided a much-needed, thorough map of the 14km by 2km marine park in which it will sit, for the local conservation authorities.

He is confident that his team are well on its way to raising the US$60 million needed to build Proteus and a further US$75m needed to run it for its first three years. The business plan is to rent out space to high-tech firms and research centres.

Talking from his home outside New York, Cousteau told DIVE: ‘As much as I enjoy all the space stuff going on, as everyone else does, it is far more important and crucial that we search for solutions right here on Earth. Just from a return on investment perspective, it makes more sense to set up a space station of the sea. We will benefit more and learn more by understanding the pressing problems facing Earth by understanding how our planet actually works, and the oceans are a fundamental part of that understanding.’

He became fascinated by the possibilities offered by underwater habitats when he took on the challenge of beating his grandfather’s record of living underwater for 30 days in a habitat called Conshelf Two in the Red Sea off Sudan. The Conshelf project in 1963 was, like many of his pioneering grandfather’s activities, a worldwide sensation, grabbing the public attention and focusing it on the wonder of underwater exploration.

The Mission 31 project 51 years later gained a fair few headlines itself, including reports that the notoriously prickly Cousteau Society, which was set up to continue the great man’s work, was ‘appalled’ by the ‘stunt’. Despite this minor family squabble, Mission 31 did manage to get underwater habitats back on the agenda. The glamour of space travel seemed to have diverted attention from such underwater exploits.

The month-long sojourn, 18 metres down off the Florida Keys, was considered a success by everyone else and definitely enthused the younger Cousteau. He says: ‘It addressed that fundamental frustration all scuba divers have at some point. Just as things are getting interesting, as the soap opera of life underwater unfolds, it’s time to go back to the surface.’

But living underwater is a very different experience to scuba diving. The Aquarius habitat, as Proteus will be, was at ambient pressure. Within 24 hours, Cousteau and his five colleagues were saturated – that is, their bodies had absorbed as much nitrogen as was possible, and as long as they stayed at the same depth, they could venture out of the habitat for up to nine hours a day scuba diving on air.

‘The reef became our home, and the marine life we were studying became our neighbours,’ he said. ‘For the first week or so, they were very skittish, and we would have to hunt for our subjects. But after about a week or two, the entire neighbourhood had become used to our presence, and things started to unfold before our eyes; natural behaviours, all sorts of nuances that you just don’t have a chance to see as a surface diver. It gave us an understanding of the rhythm of what happened over the full lunar cycle. And it was awesome.’

A particular favourite was the squadron of eagle rays that patrolled around the Aquarius habitat. ‘For the entirety of the 31 days, they would swim around the habitat,’ Cousteau remembers with delight. ‘They would come and check us out, as we were doing our experiments on the coral reef. They would circle the pod as we were inside, and we would see them out of the windows as we ate. They would quite literally buzz us when we were out diving. It was a wonderful thing to see – mesmerising. After a while, we got used to them and stopped paying attention to them.’

The aquanauts on Proteus will also breathe air and live at ambient pressure. As Cousteau explained, air is cheap, and we know much about breathing it at pressure. Later, they plan to add a deeper, mixed-gas, connected module. But as soon as you start using helium in such environments, the costs soar, as every joint in the module has to be helium-proof – its smaller molecules are able to seep through what is considered air-tight. Also, products such as soaps and shampoos can become toxic in closed, mixed-gas environments.

The plan is to make Proteus as self-sufficient as possible using ocean thermal energy conversion (OTEC) to generate power for the habitat. OTEC is a prime example of how Cousteau sees the project as being able to promote exciting technologies which could have a global impact. It harnesses the temperature difference between surface and deep waters, much like a terrestrial heat pump. Many believe it could have a major impact across the Tropics, providing cheap and clean energy and, as a by-product, drinkable water for millions. Resorts in the Caribbean and the Maldives are looking to OTEC as a carbon-neutral solution – providing power and cool water for air conditioning.

Curaçao is a prime site for using OTEC, as the volcanic island has steep drop-offs which provide quick access to cold, deep waters. ‘We are looking at Proteus being its own self-supporting colony underwater,’ Cousteau added. ‘We want to look at ideas and methods for a small community, a village of 12 to 18 people, to be able to

provide for themselves; such as growing food inside the habitat – we will have our own underwater aquaponic and aeroponic systems.’

He even acknowledges that their research in these areas could prove to be a significant boon for space exploration. Space exploration companies are one of their targets as possible paying tenants for Proteus.

Just how long the aquanauts will spend underwater at Proteus is unknown. They will be scientists, researchers and educators rather than trained commercial saturation divers. It is relatively easy to enter the habitat by diving down from the surface and swimming through a simple so-called ‘moon pool’ into the interior of the station. However, returning to the surface is not so straightforward.

It will take around 24 hours to decompress in a pressurised chamber, slowly adjusting the saturated diver’s body back to surface normality and shedding the excess nitrogen from their systems. There will be a decompression chamber in the medical bay, and a pressurised diving bell will also be able to take people to a surface chamber. Research into how aquanauts cope mentally and physically with such demands will be a key part of the project.

Cousteau is an unashamed publicist for the project. Not only does he bang the drum for the value of the scientific and research opportunities it will create, he wants to inspire and engage the widest possible public in the sheer excitement and importance of caring about our endangered oceans. Just as his grandfather captured the imagination of a generation, he hopes Proteus will inspire us all to take the plight of our seas more seriously.

‘The disconnect that we as a species have from our oceans is deeply alarming,’ he concludes. ‘While I’m a hopeful person and believe we can change, I do think we need a sense of urgency. This little blue orb contains all the life we know. We need to cherish our seas.

‘Without our oceans, we do not exist.’