Belize’s barrier reef is the key part of the second-largest coral structure on the planet. Graeme Gourlay reports on the struggle to keep this natural wonder flourishing

Charles Darwin was fascinated by coral reefs. He came up with one of the first theories about their formation and studied them extensively during his travels on HMS Beagle. His verdict on Belize’s barrier reef and connected atolls was that they are ‘the most remarkable in the West Indies’. As with many things, he wasn’t wrong.

They are part of the largest barrier reef in the northern hemisphere, which is the second-largest reef system on the planet. The Mesoamerican Reef runs along for nearly 1,000 kilometres (600 miles) along the coasts of Mexico, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras.

The richest, most varied, most glorious stretch of this natural wonder sits off Belize – a small, rectangular-shaped nation in Central America, tucked under Mexico’s Yucatán Peninsula and surrounded by Guatemala.

The reef runs along the length of Belize’s 320 km coastline (200 miles). The rise and fall of sea level over the millennia, coupled with its karst topography and clear waters, has resulted in one of the most diverse marine seascapes with a jumble of patch reefs, fringing reefs, offshore atolls and pinnacles.

The barrier reef touches the shore in the north, and it reaches 40km offshore in the south. Far out to sea, there are rare deep-water coral reefs. There is the world-famous Blue Hole – a vast sinkhole. In all, Belize’s reef system is made up of 450 different cayes (pronounced keys), three imposing atolls – Turneffe Island, Lighthouse Reef and Glover’s Reef – and is covered by seven marine reserves, which were made a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1996.

It is unique to have such a wide array of reef types in such a relatively small area. It creates a rich mix of habitats, from seagrass meadows for manatees to graze and eagle rays to swoop across, to shallow reefs dotted with vast gorgonian fans and dancing with reef fish.

This amazing tapestry of reef life includes dramatic walls patrolled by sharks, higgledy-piggledy warrens of tumbling hard corals being tended by turtles, jagged limestone canyons hiding dozing nurse sharks, coral outcrops buzzing with schools of jacks and isolated pinnacles where the occasional oceanic whitetip shark can be spotted.

It is not surprising that this is probably the most biodiverse area in the Caribbean Sea. It is home to more than 65 types of hard coral, at least 36 species of soft corals and is populated with over 500 species of fish and hundreds of invertebrates. Less than 10 per cent of the reef has been thoroughly researched, and there is much more out there to be discovered.

This is perfect liveaboard territory as there is so much to explore, and no dive is the same as the last. Today Belize offers some of the best diving in the Caribbean and it is often praised for its conservations efforts. However, it has often been a struggle to keep the reef ‘remarkable’, not only against internal conflicts but with global forces beyond Belize’s control.

In 2009 UNESCO went as far as putting the reef on its List of World Heritage in Danger, primarily over the rampant destruction of coastal mangrove forests and looming fears over oil exploration in its waters.

The government subsequently imposed a moratorium on oil drilling and brought in far stricter controls over coastal development to protect the mangroves, and in 2018 UNESCO removed it from the danger list.

The spread of marine diseases is an example of an existential threat to Belize’s reefs that, while exacerbated by local problems, is a regional, if not a global, problem. The stressed reefs in Florida and across the Caribbean have been prone to waves of terrifying coral diseases over the past 30 years, which sweep through once healthy marine systems, leaving trails of devastation.

Scientists desperately try to stem the spread of destruction, which is probably caused by our impacts on the ocean or at the very least aided and abetted by anthropomorphic changes such as ocean warming, overfishing and pollution, particularly sewage outflows.

You can see traces of previous marine pandemics in the scattering of damaged corals on most dives in Belize. The latest scare is the first cases of what is called Stony Coral Tissue Loss Disease (SCTLD) found in Ambergris Caye in the Hol Chan Marine Reserve just before our terrestrial pandemic shut down travel and tourism in the area.

SCTLD is particularly nasty, destructive and virulent. It first appeared in Florida in 2014, and there have since been a number of random outbreaks across the Caribbean. If it takes hold, it can destroy large swatches of reefs as it targets up to 30 different species of hard corals, especially brain, pillar, star and starlet corals.

The authorities of the Hol Chan Marine Reserve have asked divers to report any signs of coral diseases and to send them photographs via social media (#holchanmarinereserve).

Sustainably managing commercial fisheries is a complex and challenging process, which all too often thwarts wealthy and well-organised governments and international bodies with plenty of resources to hand.

Belize has an honourable record of balancing the need to feed its people with the responsibility of conserving its natural resources. For a long time, conservation bodies under the banner of the Coalition for Sustainable Fisheries and Oceana Belize have been campaigning to restrict the use of gill nets, both illegal and legal, in their waters.

Gill nets are a highly destructive type of fishing, harvesting all species and types of marine life in their way, and the discarded gear is often a lethal danger to endangered animals such as turtles and manatees.

Besides conservationists, one of the most important supporters of controls has been the local sportfishing industry, which is worth an estimated US$28 million a year in tourist revenues. The dramatic spread of gill nets in the region was impacting on stocks of highly prized tarpon and bonefish.

Over the years, increasing regulation over their use and stepping up efforts to stop illegal use of such nets by fishers from neighbouring Guatemala, which is significantly poorer than Belize and is often guilty of poaching her neighbour’s resources both at sea and on land, have has some success.

However, last November, after much campaigning, Belize passed a total ban on the use of gill nets. Janelle Chanona, Oceana’s head in Belize, said: ‘This is a historic moment for Belize, her people, the Caribbean Sea and, most importantly, for everyone who depends on the country’s marine resources for their livelihoods’.

As a pointer to how seriously the country takes such issues, it has a Minister of the Blue Economy, Andre Perez, who took office just after the ban was passed. He now has the difficult task of implementing the ban, negotiating with the vocal and well-organised fishing lobby and reassuring the equally vociferous conservationists that he will not water down the move.

The gill-net supporters are threatening to take the government to court, while a $2 million fund has been set up to help the 2,513 licensed fishers (an increase of 45 per cent in just over a decade) transition to more sustainable methods.

Perez showed just how difficult the balancing act between conservation and political expediency can be when he had to go on national television to deny that he was going to drop the ban.

He said: ‘To say that we are under some kind of secretive talks to lift this ban that is not true. While we acknowledge that the NGOs have assisted us by offering financial compensation to the fishing community there are some out there who say they have been left behind.

‘Now, if there are some out there who say that they have been disenfranchised by this ban then they have a right to seek redress in court.’

More than a decade ago, NGOs and governments across the Mesoamerican Reef region got together to establish clear criteria for conserving the marine environment, and the Healthy Reefs Initiative carries out regular audits to see how they are performing against 28 agreed indicators ranging from sewage infrastructure to fisheries management.

In March this year, it published its most recent audit. Belize came out top with an overall score of 70 per cent, followed by Honduras with 66 per cent, Mexico at 64 per cent and Guatemala last with a score of 62 per cent.

However, the report stressed that overall progress was still far too slow, with only three out of the 28 measures being fully implemented across the region. Belize has managed to fully implement eight of the measures.

‘We have known for over two decades what needs to be done – this Eco-Audit is evidence that some efforts are underway, but the pace of these actions is far too slow,’ said Director of the Healthy Reefs Initiative, Melanie McField.

ON LAND

Spend some time exploring inland. The Mayan archaeological sites are unmissable. One of the finest sites is Caracol (below) was only unearthed from dense jungle in the 1930s. It is the largest complex of Mayan buildings in Belize –atmospheric, enchanting and often deserted.

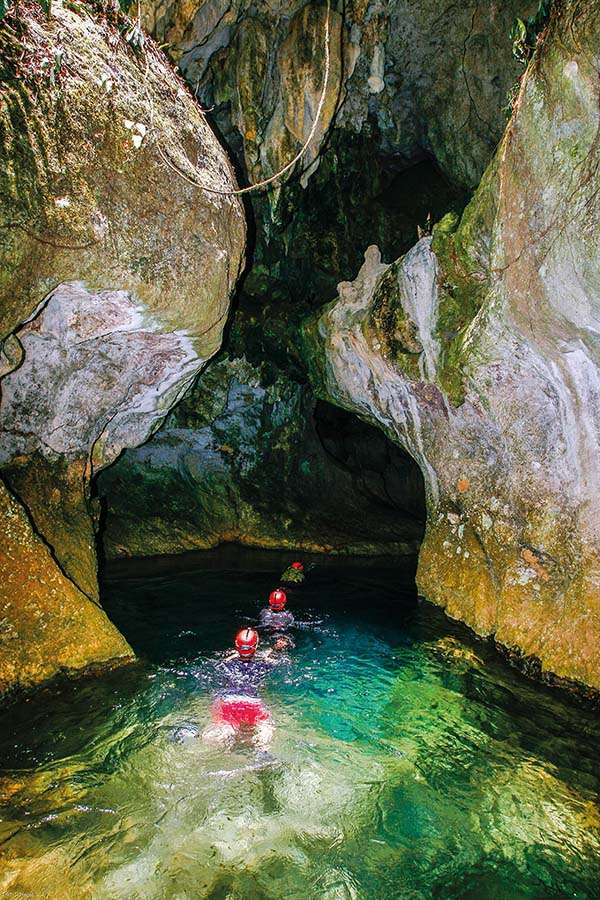

Particularly recommended is a trek and freshwater swim into the Actun Tunichil Muknal (ATM) caves (above) to see the eerie crystal skull – pure Indiana Jones.

The caves were discovered in the 1980s and contain well-preserved skeletons of Mayan human sacrifice victims. The main chamber is reached after swimming and often squeezing through tight, pitch-dark chambers that had in the past deterred looters – it is untouched and full of stunning finds.

You can explore other Mayan sites, more caves, strange pine forests, and enjoy wild jungle treks while based in the attractive small town of San Ignacio.

Lots of hotels and jungle lodges are available. Recommended is the delightful Chaa Creek on the banks of the Macal River. Stay in one of the luxury treetop lodges – it also runs a budget jungle hostel for those on tighter budgets.

The report acknowledged that Belize had made significant steps in fisheries management and the implementation and enforcement of marine protected zones. But it warned that while sanitation and sewage infrastructure across the whole region had improved it was still commonplace for inadequately treated sewage to be dumped on the reefs.

Sewage treatment is one of the bigger problems for Belize and the report pointed out that it had made no significant improvements in the past decade. It noted that, with the spread of coral diseases such as SCTLD in the area, such pollution puts the reefs at particular risk.

In Central American terms, Belize is a middle-income country – nowhere near as poor as neighbouring Guatemala, but it still faces daunting economic pressures which have been exacerbated by the Covid-19 crisis. Foreign debt has been steadily growing, while the Covid-19 pandemic switched off the tourism revenue stream, the mainstay of the economy.

This was followed by two hurricanes, Eta and Iota, hitting Guatemala; the resulting flooding destroying farms and roads downstream in Belize.

Right now, Belize owes its foreign creditors a sum equal to 85 per cent of its entire national economy, a debt the International Monetary Fund calls ‘unsustainable’. There is a growing campaign for countries such as Belize to be offered urgent debt relief.

They are trapped in an impossible position, and events beyond their control are making matters dramatically worse. Poorer countries qualify for low-interest international loans, but Belize is finding it increasingly hard to service its existing debt and recently had its credit rating downgraded, making new, commercial loans nigh on impossible.

Belize Finance Minister Christopher Coye, talking about dealing with climate change, but it could equally apply to marine conservation measures in general, said: ‘We should be compensated for suffering the excesses of others and supported in mitigating and adapting to climate change effects — certainly in the form of debt relief and concessionary funding.’

For countries such as Belize, and there are many more in similar positions, urgent international support is going to be needed for them to recover from not only the immediate impact of the Covid-19 crisis but the hammer blows of climate change and growing unsustainable debt.

For all its failings Belize has done a remarkable job in keeping the reefs that so impressed Darwin relatively intact. The global community now needs to do an even more remarkable job to safeguard those efforts and sustain them through the challenges ahead.

NEED TO KNOW: BELIZE

The best time to visit is January to July, with the calmest weather around May. July to November is hurricane season. Belize is subtropical and warm all year round, with high temperatures rarely much above 30°C, and lows not much below 20°C. Water temperatures hover around 25°C to 27°C.

* We visited Belize just before its Covid lockdown in March 2020 and returned a year later when diving and tourism was just starting to open up. On both occasions, we travelled with the Belize Aggressor IV and would like to thank the enormously helpful crew for their hospitality.

Related articles

- Review: Sharkpedia, A Brief Compendium of Shark Lore by Daniel C Abel - 24 October 2024

- Review – The High Seas, by Olive Heffernan - 7 August 2024

- The Ride of Your Life – with Maldives grey reef sharks - 19 April 2024