It’s party time both above and below the water for Francesca Page as she heads off to the Caribbean to scuba dive Tobago

An elongated oval of 41km long by 14km wide, Tobago provides a surprising amount of biodiversity within its craggy coastal fringes. The spine of the island called Main Ridge, is in fact the oldest protected rainforest in the Western Hemisphere, dating back to 1776.

It is home to 16 of the nearly 90 species of mammals found in the Caribbean region, 24 species of non-poisonous snakes,16 types of lizards and 290 species of birds – including the rare and endemic white-tailed sabrewing hummingbird.

Last year it was announced that the coral reefs around the northeastern coast of the island are to become a marine protected area. Tobago’s reefs are the most southerly in the Caribbean – its sister island of Trinidad which is nearer to the vast freshwater outflow from the Orinoco river in Venezuela, has no coral reefs.

Being just 20 kilometres further from the Orinoco Delta not only allows the reefs to grow, but to bloom. It washes them with nutrient-rich currents encouraging both hard and soft corals, and in the wet season (July to September) provides a greenish planktonic soup for manta rays to feast upon. Combined, this makes the marine environment one of the most exciting in the Caribbean for divers.

I visited in January, when the water was clear and, as a bonus, the island was gearing up for carnival. With steel drums, elaborate outfits and energetic parades, the carnival is an explosion of colour, dance and music.

As I woke up to my first morning on the island, I lay in bed listening to the sound of the waves breaking on the shore, and experiencing my whole room being lit up by the bright morning sun. A warm glow invited me to open my balcony doors to take my first peek at Tobago’s riches. While drinking coffee on the beach at the Blue Waters Inn, I couldn’t get over the tranquillity. Pelicans flew overhead while hermit crabs scurried across the water’s edge.

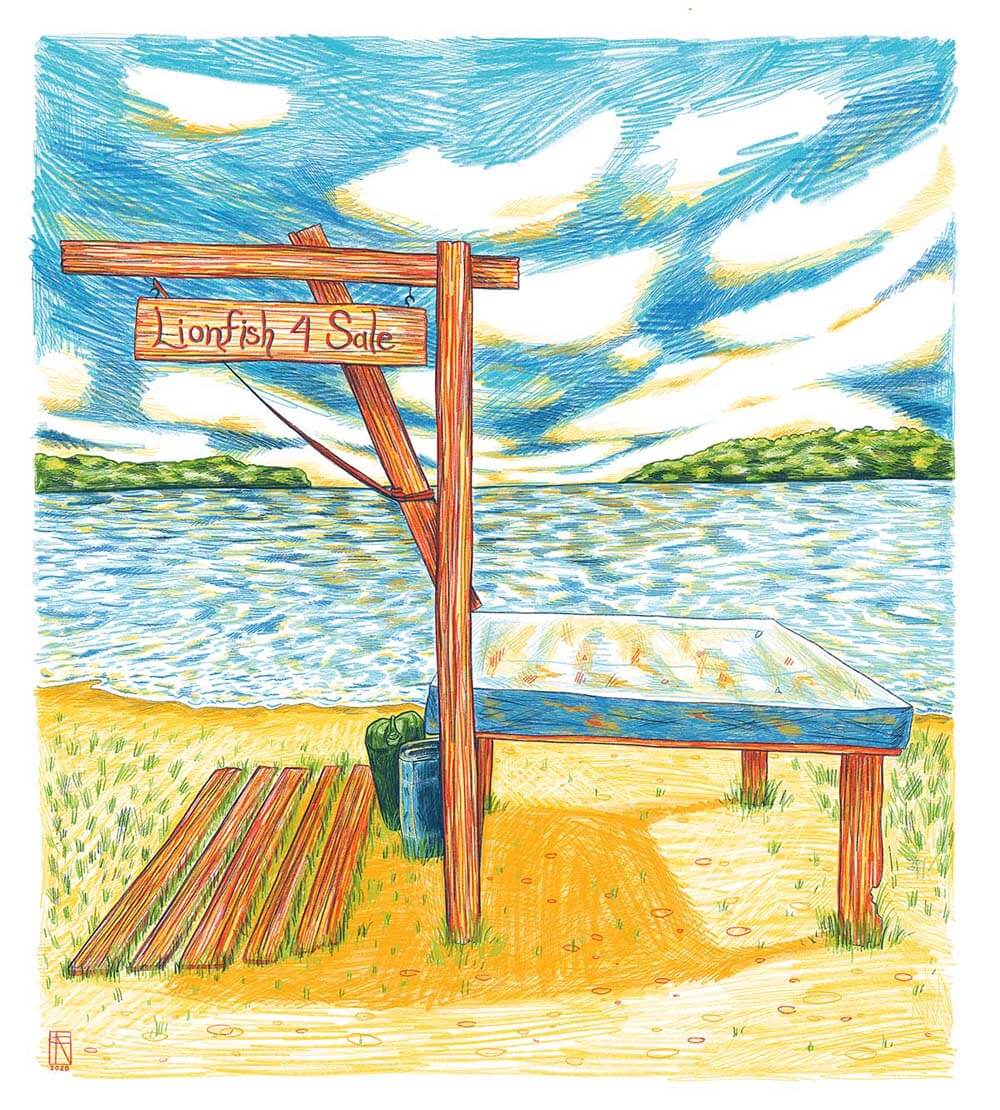

We headed to the first dive centre of the trip, the Tobago Dive Experience, a short journey from the hotel, to start the undersea adventures. In the bright sunshine we passed thick, emerald-green jungle to our right, and sparkling blue water to our left. I noticed a ‘lionfish for sale’ sign beside a metal table on the roadside – an early reminder of one of the region’s most intractable problems: the invasion of this voracious predator is cutting swathes through the Caribbean.

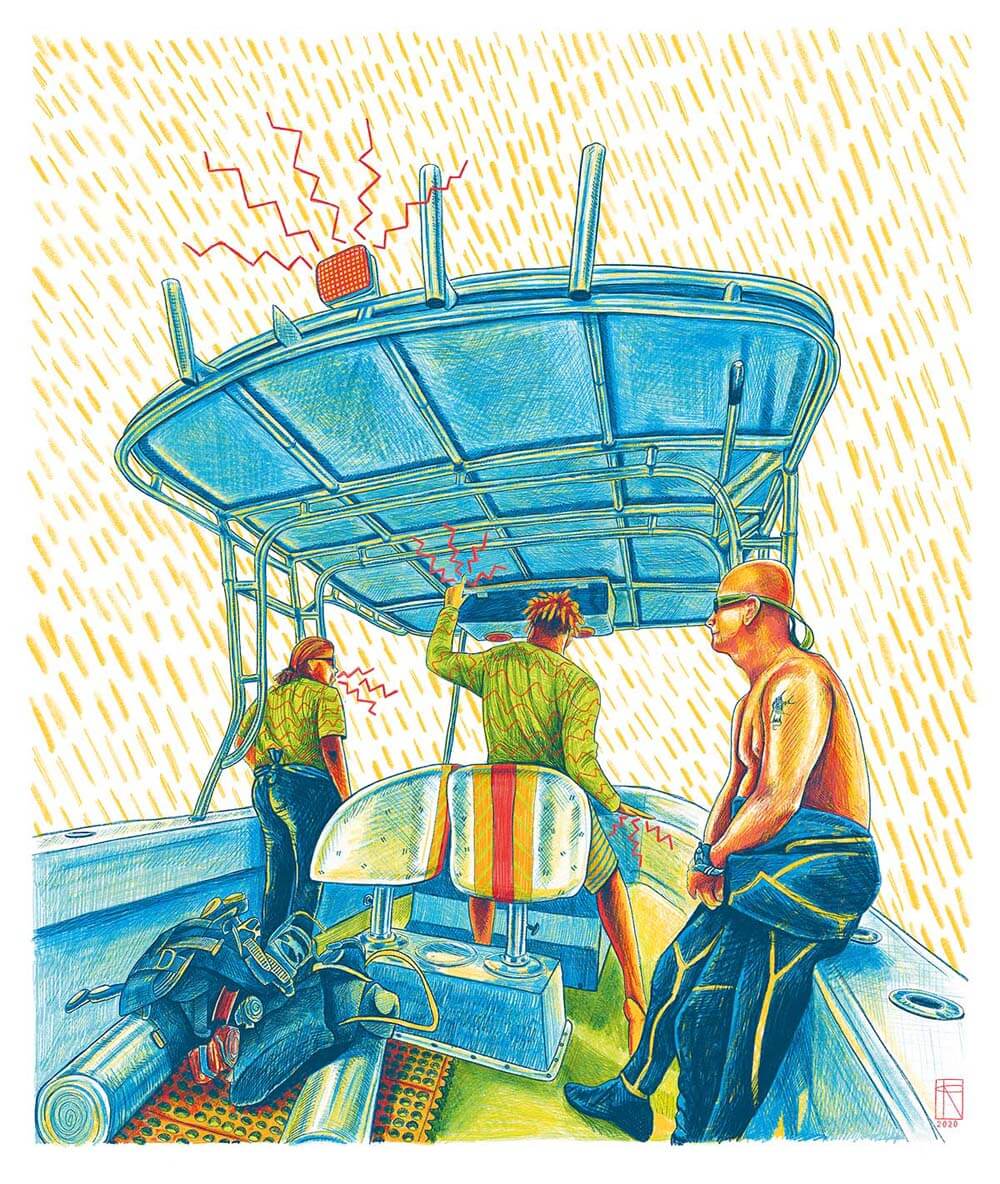

We got our gear ready and headed out to sea, with the captain blasting out carnival tunes as flying fish danced across the ocean surface. On board, the divemasters practised their own moves for the upcoming festivities.

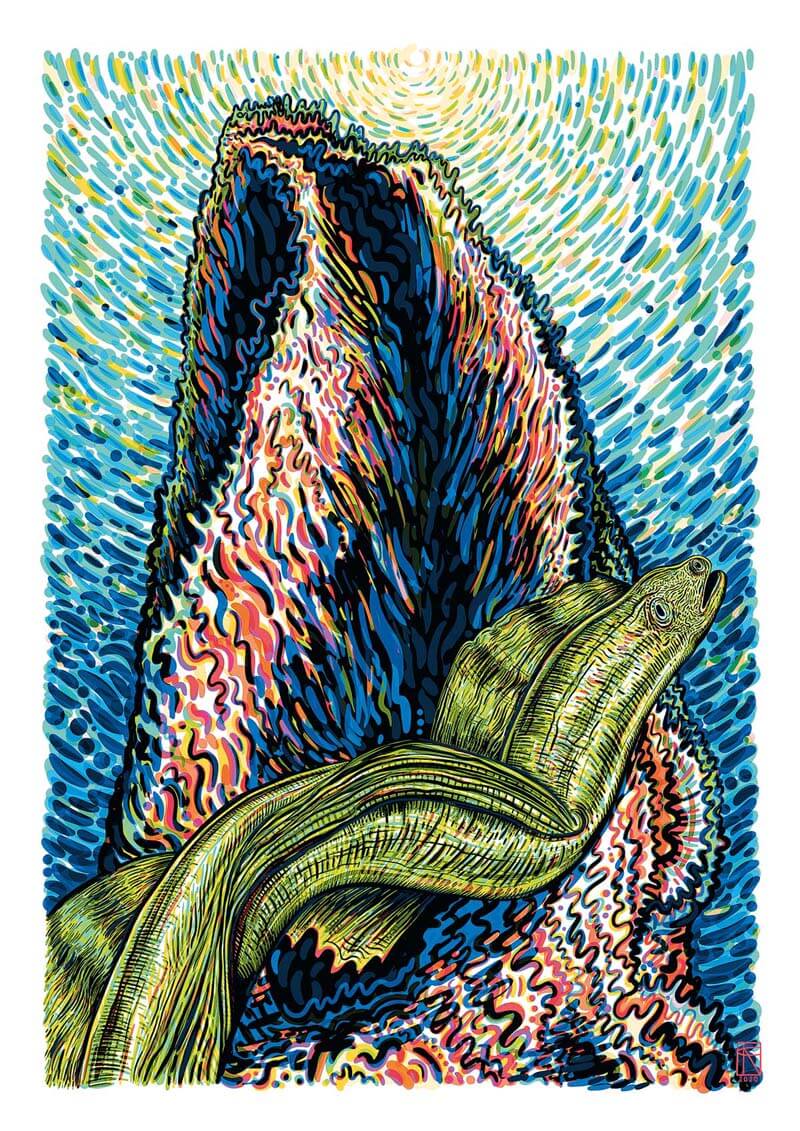

We were lucky with the first few dives, being greeted with good visibility and calm, relaxing warm water. The coral landscape was a delight for the eyes, small fish flocking between dancing giant slit-pore sea rods, massive fan corals swaying in the current, and huge barrel sponges looking more like craggy mountains, all set against a rich blue background.

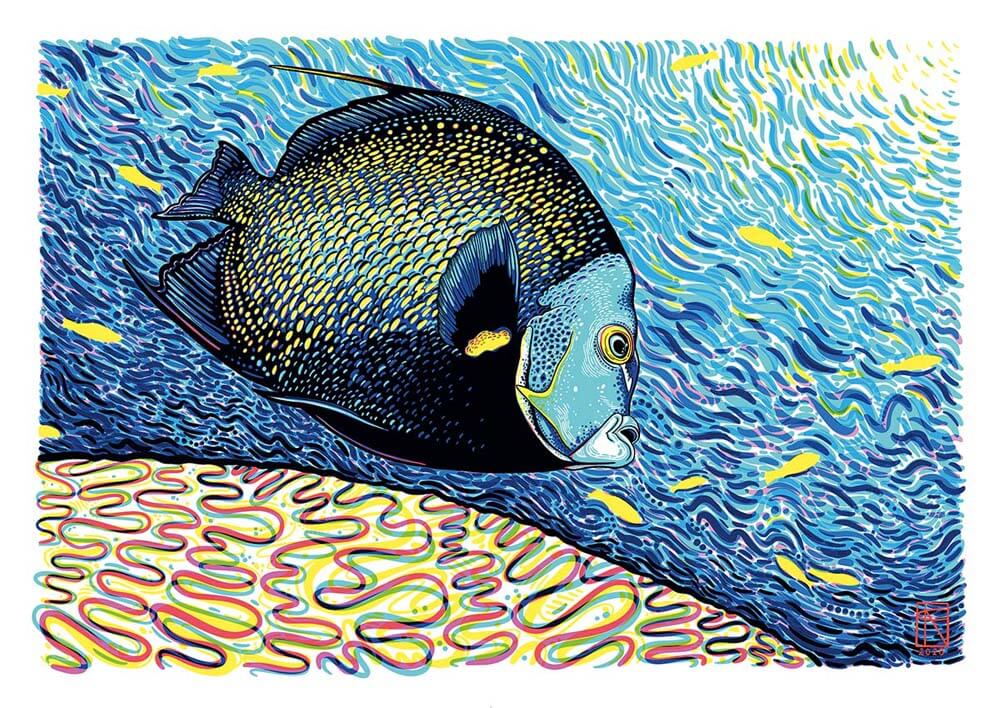

Tobago’s nutrient-rich waters explain the formation of the massive hard corals, such as the giant boulder brain coral off Speyside. In fact, Tobago lays claim to the largest brain coral in the Western Hemisphere. French angelfish were whirling over the brain corals, not shy of divers and swimming right up to you, almost inviting you to join their party.

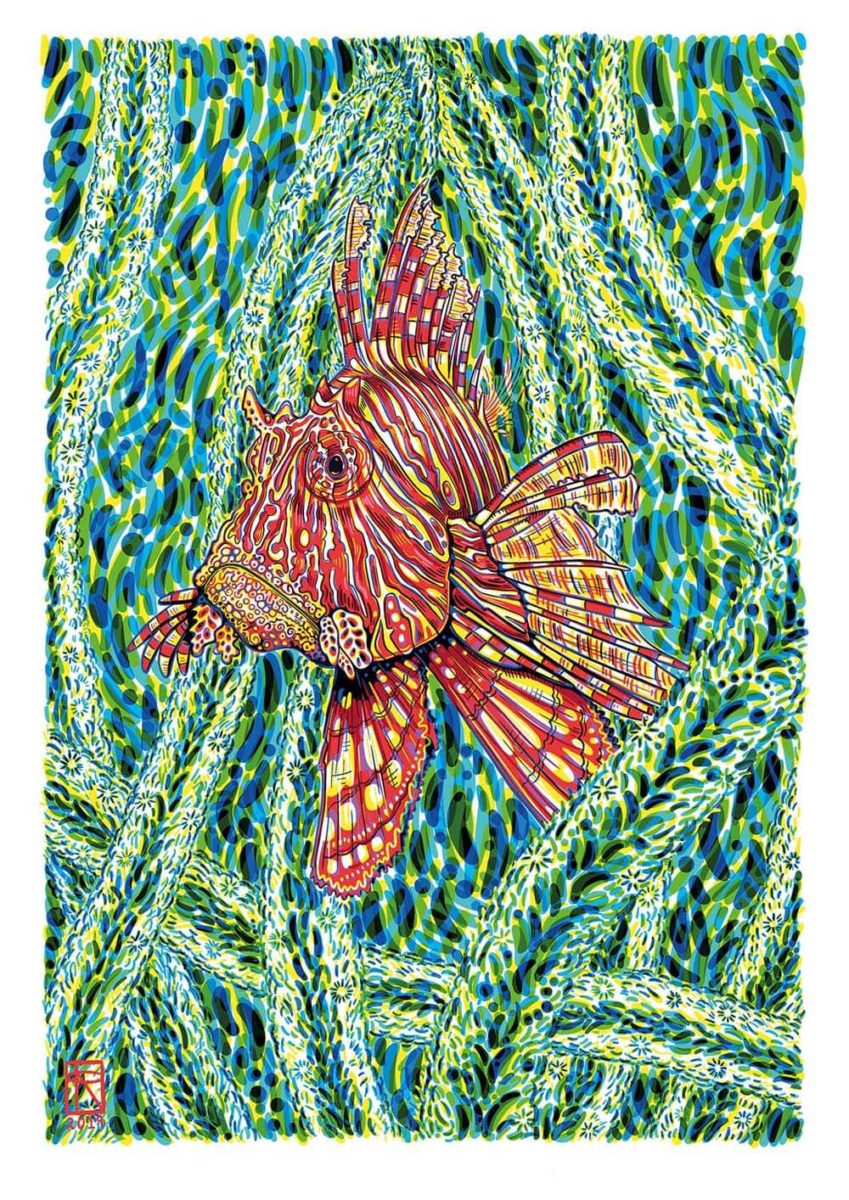

I spotted my first lionfish of the trip, gliding between the sea rods which reminded me of feather boas. The lionfish’s beautiful orange-pink fins and spines seemed to mimic the vibrant outfits worn at carnival.

During our surface interval, with the boat at rest in a small lagoon, I used the time to talk to Jon, one of the divemasters, who spends a good deal of his time trying to eradicate lionfish underwater while topside encouraging people to add the fish to their menu. ‘Aren’t lionfish poisonous to eat?’ I asked. ‘The most dangerous part about eating lionfish is catching them, so I am the one at risk’, he explained. ‘The venom is only poisonous if it gets into your blood stream. If I were to swallow the poison right now, I would be fine, as my stomach acid would destroy it.’ He added: ‘They are really tasty!’

The lionfish are wreaking havoc on Caribbean marine life. Unlike the predators of Indo-Pacific, the local sharks and other larger hunters seem to be deterred by their poisonous spines, leaving the lionfish to feed freely.

One theory explaining their arrival in the Caribbean and the Atlantic is that during Hurricane Andrew in 1992, a damaged aquarium released some specimens into Florida’s Biscayne Bay. By 2004 they had gained a foothold in the reefs off the Bahamas and have since spread at an alarmingly rate.

Lionfish are voracious and can feed on fish and invertebrates up to two thirds their size. Studies in the Bahamas by Oregon State University indicate that a single lionfish on a reef can reduce the juvenile fish population by up to 80 per cent in less than five weeks. With the plague of lionfish spreading around the Caribbean, volunteers have been playing a major role in fending them off in Tobago.

I went diving with the Environmental Research Institute Charlotteville (ERIC) to learn about coral restoration on the island. I asked one of the team how Tobago coral reefs have been affected by rising sea water temperatures common around the world, and was told that while there has been some stress seen on the corals, so far the reefs haven’t experienced any mass bleaching events. While further stress impacts were recorded in the summer of 2019, the reef was still able to bounce back, unlike some of the worse affected reefs in other areas of the world.

We left Man-O-War Bay on a small fishing boat; the small marine conservation group hires local fishers’ boats to help inject extra income into the community. We headed to our first dive site, Sail Rock. As we got further out beyond the rocky, flora-covered coastline, the weather changed, the water turned grey and the waves started to rock the boat. A marked contrast to the previous few days of diving.

As we were gearing up while trying to keep our balance, I looked up to see a small manta ray jumping out of the water creating a large splash! Mask on, regulator in, let’s go diving! The water was murkier than on previous days but this didn’t stop it being a great dive, with lots of fan coral swim-throughs and dramatic topography. We did our surface interval further north at Pirate’s Bay where we watched frigate birds flying overhead.

The team collected corals for us to plant at the local coral nursery – our next dive. Here we saw the different stages of coral growth from the coral-propagation programme, surrounded by fish and eagle rays doing flybys. This is the only place in Tobago known still to have any staghorn coral. Today, the majority of Tobago reefs are made up of soft corals, sponges and some large plating and brain corals.

In the 1970s, Man-O-War Bay was filled with staghorn corals. Due to diseases which have swept through the Caribbean, the staghorn coral has now largely gone. Through ERIC’s planting programme, they are slowly making a comeback.

We then headed across the island to the Caribbean side – what a difference a few hours in a car can make. We left the tranquillity of Speyside and entered the lively party vibes of Crown Point, colour and rhythm filling the air – carnival was here.

The diving on the Caribbean side was more relaxing, with lots of coral and some good wreck dives. You can drift-dive over galleries of intricate gorgonian corals and large barrel sponges where turtles, nurse sharks and an abundance of reef fish come out to play. The underwater landscape was covered in the most ghostly looking sponge corals you’ll ever see. The giant eels dancing around them were like green dragons from a strange fantasy film. A light current pushed us along a conveyor belt past nurse sharks sleeping underneath massive plating corals and schoolings of fish hovering over white sand.

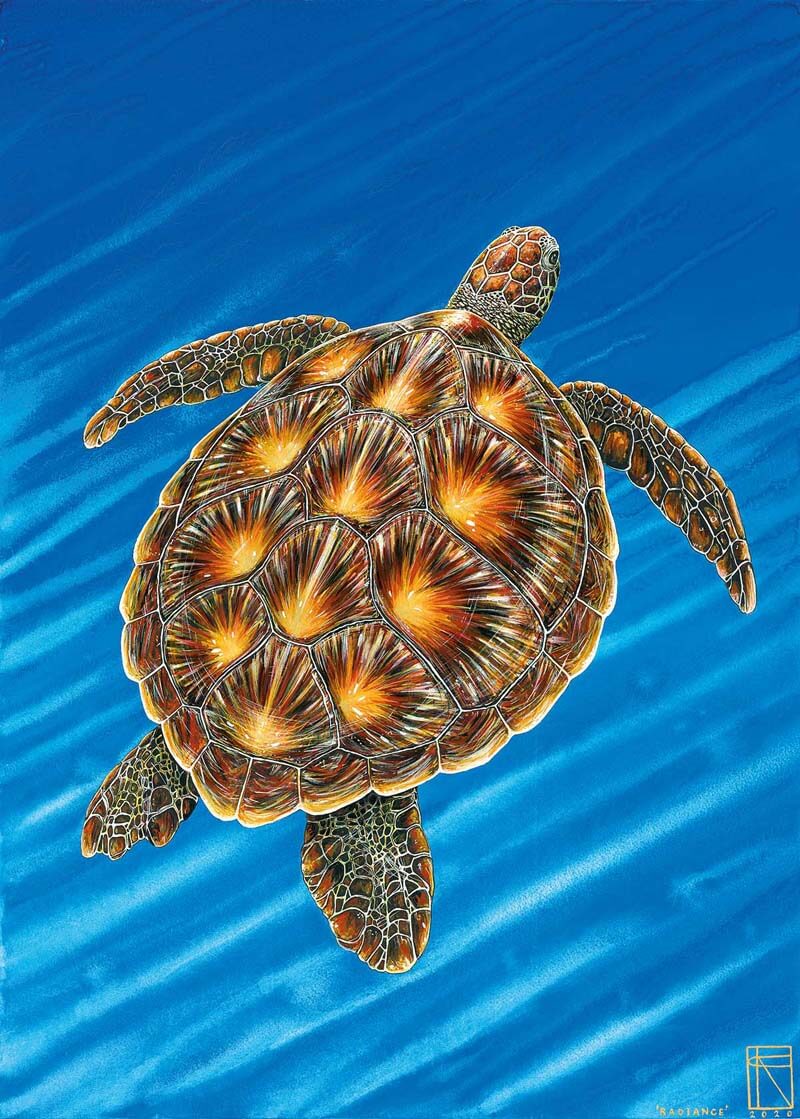

I was lucky to end the trip out in the blue waters, doing a safety stop, when I spotted a young green turtle coming up for air. The sunshine piercing the water’s surface and hitting the turtle’s shell, bestowed a radiant, golden glow.

While heading back to shore after two great dives on Coco Reef, the boat surfing on the waves and dance music playing, the weather suddenly took a turn for the worse. Sunshine quickly turned to heavy rain, which caused the captain to shout: ‘It’s liquid sunshine, everyone!’ He proceeded to turn the music up and got everyone dancing on the boat. It seemed there was a party to be had in any situation: the perfect way to end our last diving day.

Francesca stayed at: Blue Waters Inn, Speyside and The Shepherds Inn, Crown Point.

She dived with: Tobago Dive Experience, Speyside. Blue Waters Dive’n, Speyside; Environmental Research Institute Charlotteville, Campbleton; Black Rock Divers, Stonehaven Bay. Undersea Tobago, Crown Point

Thanks to the Tobago Tourism Agency for hosting Francesca’s trip. Discover more about diving in Tobago: TobagoBeyond.com