Weird and wonderful these creatures may look, but according to the studies of palaeontologists they did exist

Words by Darren Naish; illustrations by Steve White

The time was 300 million years ago, sharks dominated the oceans in a period of ecological decadence. There was an explosion of bizarre forms living in the seas, which rocked the evolutionary ladder. Sharks with curved, pointed spikes projecting from their skulls, tooth-covered spines, wing-like pectoral fins for gliding through the air; and others encased in armour-plating. The truth about Jurassic sharks really can be stranger than fiction.

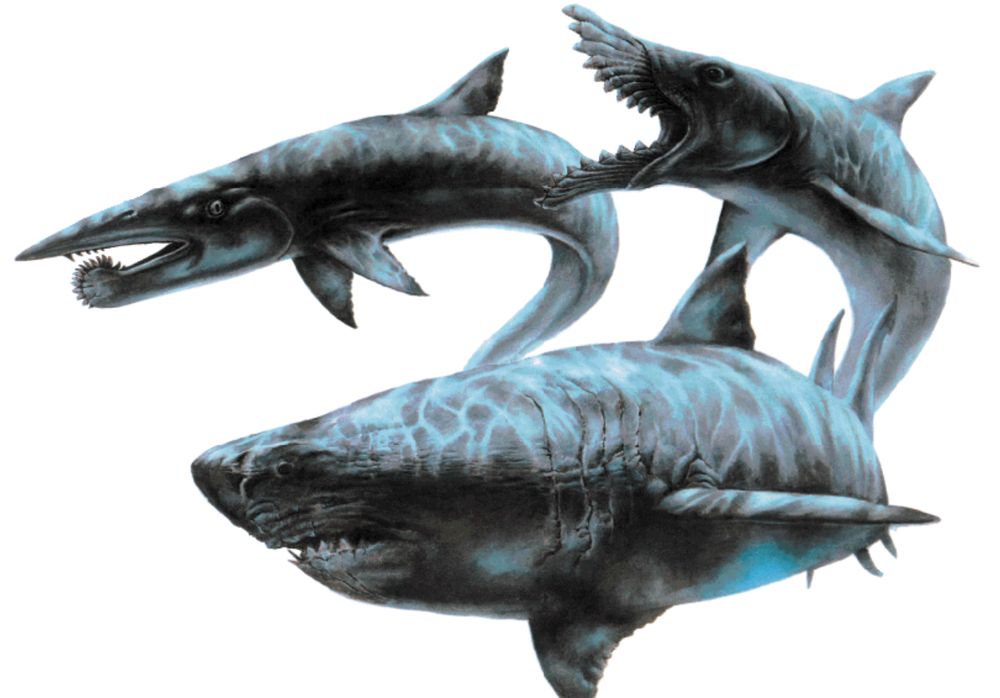

RAZOR HEAD

Cretoxyrhina mantelli, sometimes known as the ginsu mako, plied the seas of the late Cretaceous period, 85–83 million years ago. Its remains have been recovered from marine sediments in Africa and Europe, but most famously from those of the Cretaceous Inland Seaway, a shallow ocean that ran north-to-south down the length of North America; this cut the continent in two during much of the Cretaceous period.

Cretoxyrhina’s remains indicate that it was a distant relation to the mackerel sharks – the great white, mako and porbeagle. The skeleton shows that it was similar in appearance to the mako. This was especially true of the shark’s teeth, which were elongated triangles, unserrated but razor-sharp, much like a mako shark’s.

Cretoxyrhina’s prey remains a matter of conjecture but there’s plenty of evidence to show that it ate the large marine reptiles which shared the Cretaceous oceans with it. Numerous fossilized bones of mosasaurs – sea-going lizards related to monitor lizards – have been found scoured with shark-teeth marks, even savagely severed by the violent twisting motion of large feeding sharks.

The real smoking gun has been the cretoxyrhina teeth found embedded in the mosasaur bones. Of course, it is unknown whether the reptiles had been killed or were being scavenged by the sharks, but Cretoxyrhina grew to 6m in length, so it is not out of the question that it could quite easily have taken some of the smaller mosasaurs. Cretoxyrhina became extinct approximately 83 million years ago, apparently succumbing to the rise of various giant predatory marine reptiles.

LIZARD TAIL

Xenacanthus and Orthacanthus are both xenacanths – a group of long-bodied sharks that dominated freshwater environments between 400 and 220 million years ago, although they also lived in brackish and marine waters. Other, later groups of sharks also invaded freshwater environments, but none were as successful as the xenacanths. Most xenacanths were small, less than a metre long, but Orthacanthus was a giant, reaching 3m.

A peculiar feature of many xenacanths is a long spine that projects backwards from the top of the head. This structure has no clear function and does not seem to have been mobile. Xenacanths also have peculiar twin-pronged teeth and a double anal fin. Unlike more familiar sharks, Xenacanthus had a narrow, tapering, symmetrical tail and a long low dorsal fin. More primitive members of the xenacanth group, however, had triangular dorsal fins and tails like those of modern sharks, so these features in Xenacanthus were advanced, rather than primitive.

It is conceivable that xenacanths modified these features to enable easier movement through underwater clutter, as the freshwater habitats in which the sharks are preserved sometimes seem to have been weed-choked and strewn with dead leaves and broken branches. Features in the skull and fins show that xenacanths were part of a group that was ancestral to all modern sharks.

TOOTH SLAYER

Helicoprion or the tooth slayer is an absurd-looking shark from the Permian age, best known for its spiralling whorl of teeth. Such whorls were characteristic of the edestids, primitive sharks that may have been the dominant marine predators in the oceans of 260 million years ago. Like all sharks, Helicoprion was constantly growing new teeth.

However, rather than shedding its worn teeth, it retained them and was thus always adding new ones to what must have been a slowly rotating, circular conveyor belt of teeth. The older teeth, near the centre of the whorl, were grown by the shark when it was younger and therefore smaller, and consequently the teeth became smaller towards the centre of the whorl.

Early researchers were baffled by this whorl and wondered if it might have sprouted from the dorsal fin, tail or upper jaw. Only recently have scientists come to understand the true-life appearance of whorl-toothed sharks.

SCISSOR JAW

Edestus is another edestid, but one with huge, protruding triangular teeth in both its upper and lower jaws. These formed two beak-like structures that could have cut against one another like scissor blades, and presumably this is how Edestus dispatched its prey. While edestids are known primarily for their bizarre arrays of teeth, little is known about their bodies.

Unlike most modern sharks, experts believe that these sharks did not have gills, but whether or not they had dorsal fins remains uncertain. Incomplete skulls show that edestids had huge eyes, so perhaps they hunted in deep or murky waters. New evidence suggests that edestids had elongated eel-like bodies. In this case, giants such as Edestus could have reached lengths of around 30m.

MEGATOOTH

Carcharocles megalodon, the megatooth shark, is the Tyrannosaurus of the shark world: an extinct giant famous for its size, power and imagined ferocity. Known from thousands of robust, triangular teeth found in rocks – between 25 million and two million years old – virtually worldwide, Megalodon was famously reconstructed in 1909 as a 30m-long leviathan with a 3m-wide mouth.

Recent estimates suggest a more reasonable, but not insubstantial, 10–20m length. Megalodon teeth reached a maximum base-to-tip length of 17cm. Whale bones found in association with Megalodon fossils bear scars and bite marks clearly inflicted by this giant predator. It appears that Megalodon was a specialized whale killer that used immense crushing power and its stout, powerful teeth to immobilize large prey. A reduction in whale species diversity around two million years ago, together with climate change, may have been responsible for the extinction of this shark.

Controversy continues over what kind of shark Megalodon was. Some argue that it was a close relative of the living great white and should be placed in the same genus (Carcharodon). If this is correct, Megalodon would have looked much like a gigantic great white, but with a blunter, deeper head. Others contend that it was a member of the group that includes nurse and sand tiger sharks. In this case, it would have had a less spindle-shaped body, less erect tail and a lower dorsal fin than the great white.

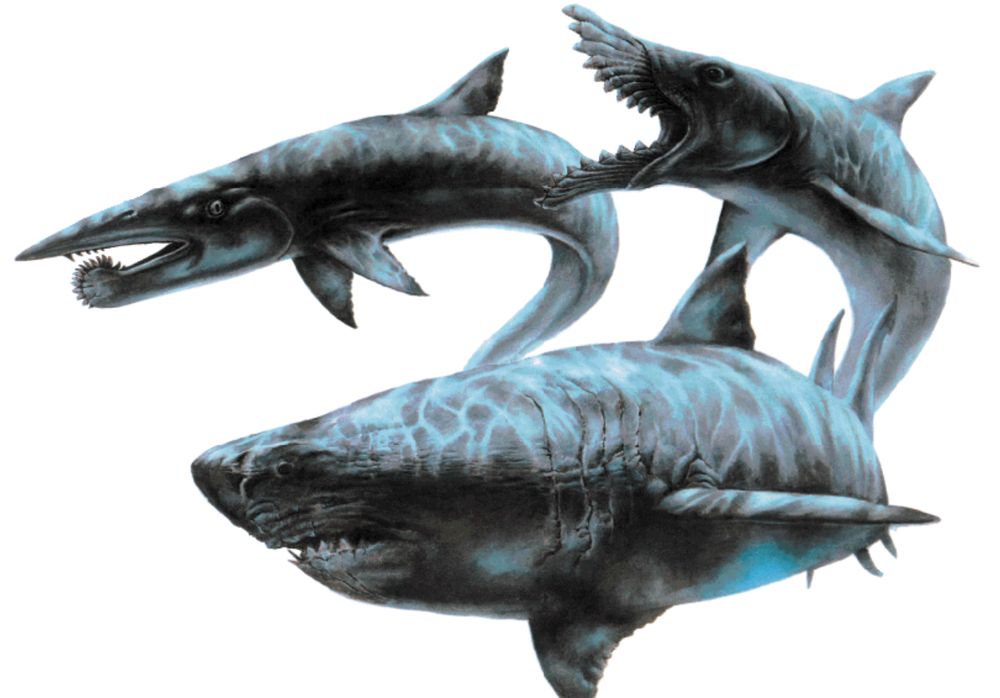

SPINE TOOTH

Stethacanthus was not unlike many modern sharks in body shape. Remarkably, however, it sported an expanded, tooth-covered spine growing upwards and backwards from its shoulder region, just in front of a modified first dorsal fin. A patch of spiky teeth also grew from the top of its head. Several suggestions have been made to explain these bizarre structures.

One is, perhaps, that when viewed from above and with Stethacanthus flexing its body up and down, they mimicked a huge pair of jaws opening and closing and thus functioned as a threat display. Alternatively, the male Stethacanthus may have used these spiky structures to grip the female’s body during mating – in fact it may be that only males had the toothy spine. Known from fossils found in both Scotland and Montana, USA, Stethacanthus was around a metre in length.

THE LUMP

Belantsea represents the petalodonts, a group that could win the prize for the most unusual group of sharks ever. Known since the 1840s for their distinctive teeth, not until 1989 was their compact, lumpy body shape revealed for the first time. Vaguely reminiscent of that seen in frogfish, perhaps Belantsea was a bottom-dweller that could clamber over rocks and shells using its stout, fleshy fins.

The teeth of Belantsea were stout, with triangular, serrated crowns. Perhaps they were used for rasping at coral or breaking into mollusc shells, a diet supported by the presence of armour plates around the mouth. These could have served to protect the face from abrasive foodstuffs. The tail of Belantsea was tiny, suggesting that when it swam, it did so by oscillating its dorsal and pelvic fins, much like modern wrasse and parrotfish. Like other sharks, Belantsea was covered in tiny denticles that grew from its skin.

SPINY TAIL

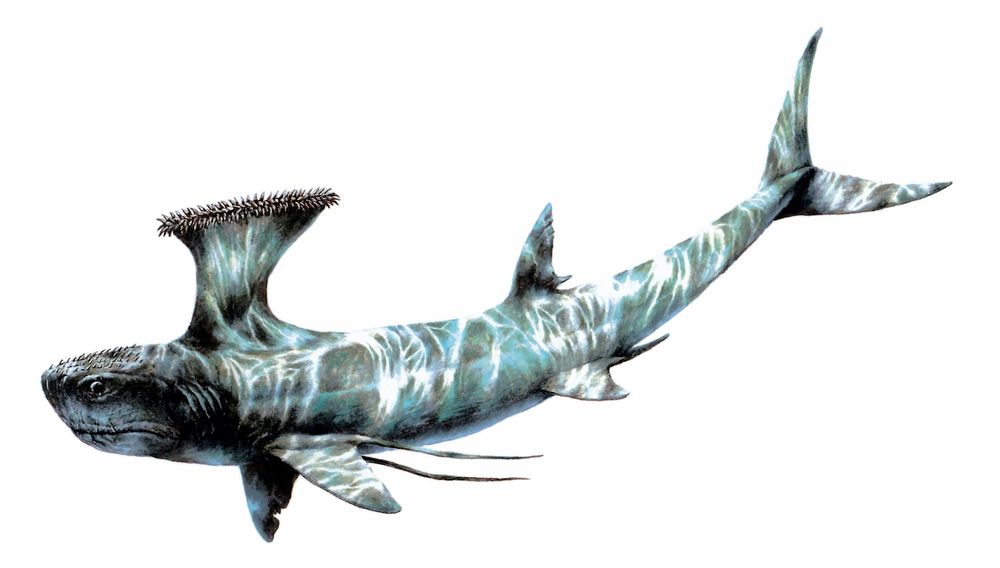

Echinochimaera was a highly decorated chimaera, less than 10cm long, known from the 325 million-year-old rocks of Bear Gulch in Montana, USA, the same locality that has yielded Stethacanthus, Belantsea and many other fossil sharks.

Chimaeras, sometimes called ratfish or rabbitfish, are not sharks but their close relatives. Virtually all chimaeras, including Echinochimaera, have flattened crushing plates in their mouths which they use to dismember molluscs and crustaceans.

They have wing-like pectoral fins and elongated tails, often with a whip-like tip. Male and female specimens of Echinochimaera are known. As with some living chimaeras, males had spikes on the head as well as rod-like claspers beneath the tail. Both sets of structures would have been used to grip the female during mating. Males also had a row of spikes running along the top of the tail. The spiky profile of this little animal provided the inspiration for its name, Echinochimaera meaning ‘spiny chimaera’

THE WINGED WARRIORS

Promexyele, Iniopteryx and Iniopera represent the iniopterygians – a bizarre group of small, open-water sharks that had massive wing-like pectoral fins, large blunt heads and rounded tail fins. The huge pectoral fins of iniopterygians had hooked spikes along their leading edges, the function of which are a mystery, and are attached to the body very high up on its side. This and other features indicate that the fins of these sharks could be flapped up and down and that iniopterygians therefore flew underwater like modern-day penguins and turtles.

Today chimaeras, the closest relatives of iniopterygians, have much smaller fins but they too swim in this way. In contrast to chimaeras, the enormous fins of the iniopterygians are similar to those of flying fish. Perhaps, therefore, iniopterygians also used their fins in gliding through the air, a defensive tactic evolved to evade pursuing aquatic predators.

THE SWORD BEARER

Damocles, a close relative of Stethacanthus, is named after a character from Greek mythology above whose head a sword was suspended. In Damocles, this ‘sword’ was a curving, forwardpointing spike that projected from the back of the skull, thought perhaps to have been a sexual organ.

As with many modern sharks, the males had longer, slimmer teeth than the females – female specimens of Damocles have only been discovered very recently and they lack both the ‘sword’ and the long, slim teeth. Male specimens of Damocles had clusters of enlarged skin teeth (denticles) on their spike and on the top of the head. Further clusters were located on the side of the head and front part of the body. Damocles had huge eyes and a tail with triangular, symmetrical upper and lower lobes. These features suggest that it was a pursuit predator that hunted other fish by sight.

RAISED IN ARIZONA

To see the sharks that roamed the Bear Gulch and those of the Carboniferous and Permian ages, you would have dived in the Tethy ocean – a huge sea that surrounded the supercontinent of Pangea. Xenacanthus and Orthacanthus were from the rivers of the Chinle formation in what is now Arizona. Cretoxyrhina swam the Sundance Sea that ran down the centre of North America during the late Cretaceous period – the end of the Age of the Dinosaurs, about 75 million years ago. Carcharocles Megalodon swam in what are essentially our modern oceans.