If there’s one shark that everybody knows – and many fear – it’s the great white shark. Here’s an introduction to their their history, biology, and association with humans, so we can stop worrying about being eaten by them, and worry more about never seeing them again

Why are they called ‘great white’ sharks?

The origin of the term ‘great white shark’ is hard to pin down, although it may have arisen during early attempts to classify the species, as many sharks, let’s face it, appear quite similar to the casual observer.

Ostensibly, the name comes from the shark’s white underside which, due to the shark’s behaviour and manner of feeding, was often more visible than other species of shark, which rarely break the surface. The colour, coupled with its pointed snout, earned the great white the moniker ‘white pointer’ in Australia.

The ‘great’ may have been added to distinguish great white sharks from oceanic white-tip sharks, which were at one point known as ‘lesser white sharks’. There has been a move in recent years among scientists to drop the ‘great’ part and refer to them simply as ‘white sharks’, as calling them ‘great’ still implies there is a ‘lesser’.

The unanimous vote from this side of the aisle is that they are great, and shall remain so!

Taxonomic classification of great whites

The scientific name of the great white has little in common with its colouration, referring instead to the shape of its teeth.

The first record of the great white shark appears in 1553 in the French naturalist, Pierre Belon’s excellently titled: De aquatilibus, libri duo cum eiconibus ad viuam ipsorum effigiem, quoad eius fieri potuit, expressis, which translates (roughly) as: On the aquatics, two books with icons in their vivid likeness, as far as possible.

Belon named the shark Canis carcharias, identifying them as being similar to dogs (canids), with the carcharias part derived from the Greek word καρχαρίας (karkharías), which means ‘shark’.

In 1554, French physician Guillaume Rondelet, in his book Libri de piscibus marinis, in quibus verae piscium effifies expressae sunt (books about marine fish, in which real fishes are depicted), described the shark as ‘Lamia’, a female demon of Greek mythology, who enjoyed eating children. Rondelet also thought it likely that this was the fish, not a whale, that ate the Biblical Jonah.

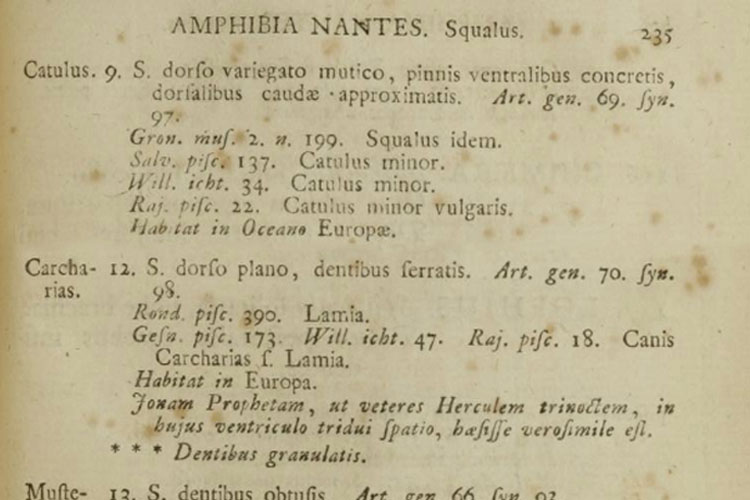

Carl Linnaeus named the shark Squalus carcharias in his 1758 ‘bible’ of modern classification, the 10th Edition of Systema Naturae, in which all sharks are labelled squalus, the Latin name for shark (meaning Squalus carcharias, therefore, sort of translates as ‘the sharky shark’), and all squalus are described as Amphibia Nantes – swimming amphibians.

Linnaeus describes the shark as having a dorso plana – flat back – and dentibus ferratis – iron teeth – and also seems quite taken with the idea that Jonah was eaten by a great white. Neither he nor Rondelet, however, explain how Jonah got out.

The current taxonomic name of the great white, Carcharodon carcharias, was partly coined by British surgeon and zoologist Sir Andrew Smith, in 1838, when he proposed the name Carcharodon to encapsulate a group of sharks with a particular form of tooth, of which the great white is the only living species.

Carcharadon comes from the Ancient Greek words κάρχαρος (kárkharos), meaning jagged, and ὀδών (odon), meaning ‘tooth’, and in 1878 the term was combined with Linnaeus’ carcharias to form the term we use today, essentially, ‘the jagged-toothed shark’

With a bit of etymological gymnastics around the Ancient Greek, it’s also not that far away from being interpreted as ‘shark-toothed shark’!

Are great white sharks related to megalodon?

Sharks as a whole have been around for some 450 million years – far older than the dinosaurs – but as cartilaginous fishes, they lack the bones that we find readily fossilised in other animals. Consequently, all that science has in the fossil record of sharks are teeth, but knowing the precise nature of what they were once attached to is a bit like playing ‘pin the tail on the donkey’ – in the dark, and without a donkey.

For many years, it was thought – perhaps ‘assumed’ would be more correct – that great whites were descended from the infamous Megalodon, mostly because they had similarly shaped, large and pointed teeth. Such animals were lumped together in a group known as ‘megatooth’ sharks – the Otodontidae – from which Otodus megalodon was the largest, at an estimated 20m in length.

A 2012 discovery, however, shed doubt on the great white’s heritage, with the description of a new species, Carcharodon hubbelli, from a remarkably intact fossil jaw with a full set of teeth.

Whereas megalodon had teeth that were similar, but not exactly so, to those of the great white, the new discovery’s teeth appeared to be a direct transition between those of Carcharodon hastalis – the ancestor of the modern, fish-eating, mako shark – and the great white, now thought to be the mako’s mammal-eating cousin.

Great whites are estimated to have appeared in the evolutionary timeline somewhere between 10 to 4 million years ago, during the late stages of the Miocene era and the early Pliocene. The study dated the ancient ancestor of the mako to at least 6.5 million years ago, and the discovery of a fossilised great white nursery in Chile was dated within a similar timeline.

Based on the new evidence, it seems reasonable to assume that great whites have been around for at least 5 million years, and were, potentially, direct competitors with megalodon, which is thought to have disappeared a minimum of 2.5 million years ago – and was almost certainly not related.

Where do great white sharks live?

Great whites are distributed across the globe, and are mostly encountered in temperate, coastal waters ranging between approximately 12 – 24C. The largest populations are around the Atlantic coast of the northeastern USA, the southwestern USA off California and the Pacific coast of Mexico and Ecuador; Australia and South Africa. There is also a sizeable population in the Mediterranean Sea.

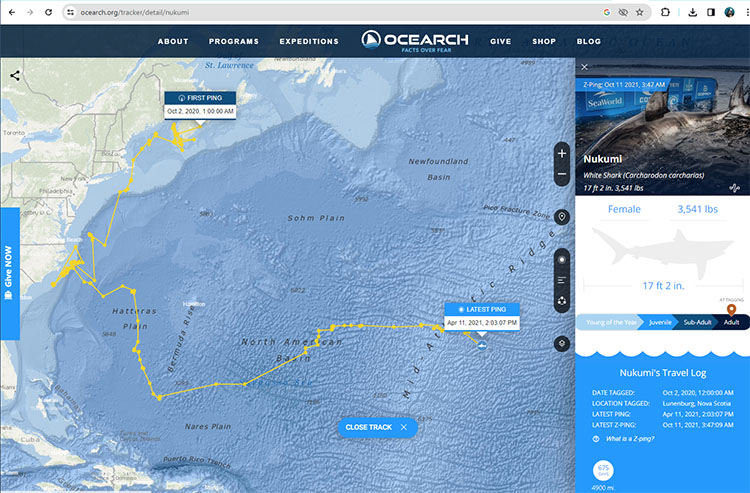

Great whites were long thought to be a primarily coastal species, but tracking over the last few decades by Ocearch has found that they navigate vast distances across the open ocean before turning up in sometimes unexpected places.

They are epipelagic fish, spending most of their time near the surface, but occasionally dive down into the depths to do some deep shark stuff, but we don’t know what that is.

Are great white sharks warm- or cold-blooded?

Great whites are one of only a few species of fish that are able to partially regulate their own body temperature, a phenomenon known as ‘regional endothermism’ which is shared with species such as tuna and – as recently discovered – basking sharks, a close, if pleasantly unlikely, relative of great whites.

Regional endotherms possess blood-rich ‘red’ muscle tissue throughout their cores, surrounded by a network of blood vessels known as the rete mirabile – or ‘miracle net’ – which also surrounds the shark’s vital organs.

They are also very big fish and their large body mass is compacted into a very round, torpedo-shaped body, giving them a very low surface area from which they might lose heat, in comparison to their internal volume – a proportional physiological response known as gigantothermy.

This ability to maintain their body temperature above that of their surroundings is what defines the range of the great white shark: not too hot, not too cold, but just the right temperature of awesome.

How large are great white sharks?

Great whites are very big fish, but possibly not as big as people imagine them to be. Males are smaller than females, averaging around 3.7m (12ft) while the larger females average around 4.7m (15.5ft). Pups are born, on average, at around 1.2m (4ft) in length.

For some years the Guinness Book of World Records listed the largest great whites ever measured at 10.9m (36 ft) for a specimen caught in Australian waters in the 1870s and an 11.3m (37ft) shark caught in 1930s Canada. Researchers later discovered, however, that the size of the Australian shark’s jaw indicated it was a comparative tiddler at just 5m in length, and the Candian fish almost certainly a mistakenly reported basking shark.

The largest great white on record measured a verified 6.1m (20ft) in length, weighing in at just shy of 2 metric tonnes, a record possibly equalled by social media favourite, Deep Blue, a giant great white spotted off the coast of Guadalupe Island, Mexico and later feasting on a whale carcass off Hawaii.

The largest preserved great white specimen is a female measured at 5.83m, now on display at the Musée cantonal de Zoologie in Lausanne, Switzerland. The 10m (33ft) monster white sharks are probably apocryphal – although you never know…

Great white life cycle and reproduction

Like most sharks, great whites mature slowly, with current research suggesting that males don’t reach sexual maturity until 26 years of age, and females even later at 33. A 2014 study found they may live as long as 73 years, and possibly even longer.

Little is known about where great whites go to mate, or what they do when they’re doing it. The only detailed report of such an encounter is from a New Zealand fisherman Dick Ledgerwood, who observed two great whites mating in 1997, but whose story was not reported until a 2020 article in the Guardian.

According to Ledgerwood, it took place in relatively shallow water, and the sharks were definitely taking their time over the procedure, but despite this encounter giving rise to a variety of theories as to the mating behaviour of great whites, nobody appears to have witnessed a repeat.

Great whites are ovoviviparous, meaning the eggs hatch inside the female and develop into fully-formed youngsters before birth, following a gestation period of 11 months. Pups are born in litters of between 2-10 young, although larger litters have occasionally been recorded.

Young great whites spend their time developing in shallower, warmer water than their parents, and there are a number of known sites around the globe that serve as great white nurseries.

What do great whites eat?

Like most sharks, especially those that traverse the deep oceans, great whites are opportunistic predators. You can’t be too picky out in the empty ocean so if you’re hungry and spot a passing turtle, then turtle is on the menu.

Juvenile great whites will prey on small fish, rays and crustaceans but as they grow in size and range, so does their diet. Great whites will eat dolphins, seabirds and turtles; scavenge the carcasses of dead whales and even hunt other sharks, but one of the prey animals with which they are most commonly associated is seals.

Each year, great whites will arrive in numbers at hotspots in the northeastern and southwestern United States, Mexico and South Africa to hunt among the vast colonies of seals, with which they have become inextricably linked.

Grey seals were virtually hunted to extinction around the coast of Maine and Massachusetts and, as a result, great whites all but disappeared from the area. Since seal hunting was banned in the 1970s, the population has rebounded – and so have the great whites.

Without the sharks, the seals take too many of the fish bound for the human markets – a simple, but resonant example of why we need sharks in our waters, and why they need us to protect them.

Are great whites dangerous to humans?

Of all the sharks that have been given a bad reputation, the great white has definitely been given the greatest. It is true that it is responsible for more recorded – the word ‘recorded’ being important – biting incidents or fatal attacks than any other species of shark – at the time of writing, the Global Shark Attack File lists 492 incidents and 157 fatalities from great white encounters since 1901.

Put in the context of the millions and millions of people who have entered the water in great white habitats in the last 123 years, that’s an incredibly small number. Around 30,000 people each year are killed by dogs, five orders of magnitude greater than the 4 or 5 people killed by great whites, and an insignificant number compared to the million people each year killed by mosquitos.

The danger was greatly exacerbated by Steven Spielberg’s 1975 film, Jaws, based on Peter Benchley’s 1974 novel of the same name. The supposed threat of shark attacks became engraved into the human consciousness, and flotillas of shark hunters headed out to sea to rid the oceans of this supposed threat to humanity – and thousands of sharks were killed as a result.

Peter Benchley later devoted the remainder of his life to shark conservation, saying that he would never have written the book if he had known how great whites really behaved in the wild. Spielberg later echoed Benchley’s statement, saying that he ‘regretted the decimation of the shark population because of the book and the film.’

Neverthless, despite the risk of an attack being very small, great whites are massive, powerful animals, and extreme caution should be exercised in areas where they are known to swim.

Human threat to great whites

While great whites have received protections in some of the regions where they were most enthusiastically targeted by hunters, they are under constant threat of being caught as bycatch by the fishing industry. In other areas, such as Australia, they have been targeted as part of the mass culling of large sharks, in order to protect swimmers and surfers.

Like all shark species, great whites are victims of the illegal shark finning industry; their size, strength and fearsome reputation meaning their fins are prized by inadequate men who believe they can make themselves more attractive by supping a bland and tasteless shark fin soup.

More than 100,000,000 sharks are killed by humans each year, and although it’s impossible to quantify how many of those are great whites, it is certain to be more than the number of humans killed by great whites.

Great white sharks are currently listed as ‘Vulnerable’ on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, and while there has been a significant upturn in the number of great whites in the North Atlantic, it still falls short of where it should be, and their population overall is globally in decline.

The survival of apex predators is essential to the balance of every ecosystem on the planet. Great white sharks pose very little danger to humans, but their removal from the oceans would devastate the populations of other species, a greater threat to humanity than meeting them face-to-face could ever be.

- DIVE’s Big Shot Light and Shadow – win an Aggressor Adventures liveaboard trip - 23 January 2026

- Huge Search and Rescue operation underway for missing Philippines divers and crew - 23 January 2026

- British Antarctic Survey opens applications for Antarctica jobs - 22 January 2026