Mythology depicts many cephalopods as vengeful man-eating monsters that grab whole ships with their fearsome arms and tentacles, but in reality they’re intelligent, inquisitive invertebrates that fascinate and flummox in equal measure

Words & photographs by Francis Banfi

They appeared on Earth about 500 million years ago and today live in all the oceans of the world. There are at least 800 living species, and surprisingly little is known about most of them. Throughout history, they have been characterised as sea monsters, creatures of unimaginable terror reaching up from inky depths to ensnare unsuspecting sailors – despite the fact that most species are small and nocturnal and generally try to pass unnoticed. And if you can win their trust, you can have hours of fun playing with them.

Cephalopods – creatures such as octopus, squid and cuttlefish that are members of the Cephalopoda (‘head-foot’) class – are widely acknowledged as being extremely intelligent; cryptic behaviour is their main defence, as few are poisonous. Their soft bodies are unprotected, possessing no tough scales or defensive spines. Some have been known to mimic other poisonous creatures, but mostly they blend perfectly into their surroundings – their camouflage is so efficient that they have been known to fool each other. Some possess an ink sac for defence, from which they squirt a thick, dark ink to confuse their predator or prey.

Cephalopods have the most advanced nervous systems of all invertebrates, and many are known for their spectacular ability to change their skin colour. They can blend instantly into the background or produce a startling array of patterns and hues for communication. Their secret is the two distinct layers of cephalopod skin that work independently: the inner layer of iridophore cells is iridescent and reflects polarised light; the outer layer is made up of pigmented organs, or chromatophores, which expand or contract to help change the colour or pattern of the skin.

Cuttlefish, octopus and squid have a visual system to match the complexity of their skin. Unlike their vertebrate predators, they can detect differences in polarised light. They fly jet-propelled through the sea by taking in water through the gills then forcing it through the hyponome, a muscular funnel or syphon. Using this method, they would usually move backwards, but, by aiming the hyponome in different directions, they control their direction. Sometimes, octopus will favour walking along the seabed, while cuttlefish and squid can also manoeuvre in any direction with the aid of a skirt of muscle that ripples around their mantle.

Because they have a short lifespan and spawn only once in a lifetime, cephalopods are at risk of being overfished – for example, cuttlefish off southern Australia and squid in the Gulf of California. Currently, there are no management restrictions in place to limit the number of cephalopods that can be taken, but there is pressure to add the giant cuttlefish to the endangered species list.

SQUID

Most of my squid encounters have been at night, from the Humboldt squid (Dosidicus gigas) to the tiny bobtail squid (Euprymna scolopes) flashing iridescent green in a sandy area on the wall. Nowadays, only hungry sperm whales, diving to depths of 1,000m, have faced living specimens of the biggest squid on earth, the giant squid (Architeuthis), reminiscent of the monster in Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.

The Humboldt squid, although smaller than the giant squid, possesses a more advanced musculature so is capable of much greater strength. It is known to be highly aggressive, and can even show cannibalistic behaviour towards injured members of its species.

Armed with these dispiriting facts, I went to the Gulf of California, just off Santa Rosalía, where Humboldt squid gather in large schools. In open water and in the dark of night, the poor visibility was made worse by the expelled squid ink. I found myself surrounded by a group of Humboldt squid that peeped in and out of my field of vision. The red colour of the strobes on my camera proved attractive to them (a white strobe would be too bright for their huge eyes).

As they became familiar with me, they started to gently explore my body with their tentacles and arms. Rows of sucker discs, each containing tiny teeth, line their eight arms and two tentacles and are normally used to grasp prey; they also tickled me through my wetsuit.

NAUTILUS

The nautilus is the only living cephalopod to retain an external shell. The chambered nautilus (Nautilus pompilius) is unique in its family in many ways: it has 60–90 thin tentacles with no suckers and primitive eyes that are comparable to a pinhole camera. A nautilus shell is chambered inside; the animal itself inhabits only the outermost (apertural) chamber. Only a thin strand of the nautilus’ body, the siphuncle, reaches through the other chambers. It helps the nautilus to change the gas content in each chamber and thus the shell’s buoyancy. Less gas in its shell chambers makes the nautilus sink; more will make it float – just like a submarine blowing the ballast tanks.

Unlike many species of cephalopod that live for a few years and die after reproducing, the nautilus is believed to have a lifespan of 20 years or more. A male nautilus can be recognised by its specialised reproductive organ, the spadix, comprising four tentacles that transfer a sperm packet to the female.

The nautilus is a slow swimmer and is predominantly a scavenger. It is rare to see it in its natural habitat, as it usually only occurs at a depth of 150–200m. During the night, it performs migrations towards the surface in search for food, close to the walls of the reef. On one occasion, off the coast of Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea, under an incredible array of stars glittering in the night sky, I was able to photograph this elusive creature of the deep. They are the absolute masters of buoyancy and deep diving.

CUTTLEFISH

It’s a fact: these camouflaged cephalopods are among the most fascinating critters of the reef. Cuttlefish zip about vertically and horizontally, their fin appearing blurred like hummingbird wings. As they move around, they flash amazing colour changes, creating patterns that pulse and shift and shimmer on the canvas of their skin. They are master predators, stalking their prey with cunning and attacking with accuracy, speed and skill. Why they have W-shaped pupils, though, remains a mystery.

If you meet one during a dive, stop and take your time without disturbing it – you’ll observe some interesting behaviour and some colourful displays. A belligerent male will often flourish its tentacles, waving them in an intimidating display that really makes it look like a creature from another world.

The pharaoh cuttlefish (Sepia pharaonis) usually shows curiosity towards divers if left undisturbed, and will come close to investigate their human observers, occasionally allowing gentle touching and giving the impression that it is somehow trying to communicate. It is a fascinating creature that can camouflage itself instantly, confuse its predators with a blast of foul ink and enrapture its prey with an incredible display of visual hypnotism.

Much smaller, more static but infinitely more colourful, the legendary and much sought-after Pfeffer’s flamboyant cuttlefish (Metasepia pfefferi) is well worth highlighting for its beauty and rarity. Rather than swimming, this species prefers to walk the substrate on two front tentacles and two skin flaps located on the underbelly. It is active in daylight hours and puts on dazzling displays of red, yellow, white and pink chevrons that move up and down its body, pulsating in a mesmerising rhythm. But beware: recent research has found that the flamboyant cuttlefish is highly toxic, and these vibrant colours and patterns might constitute an aposematic warning.

OCTOPUS

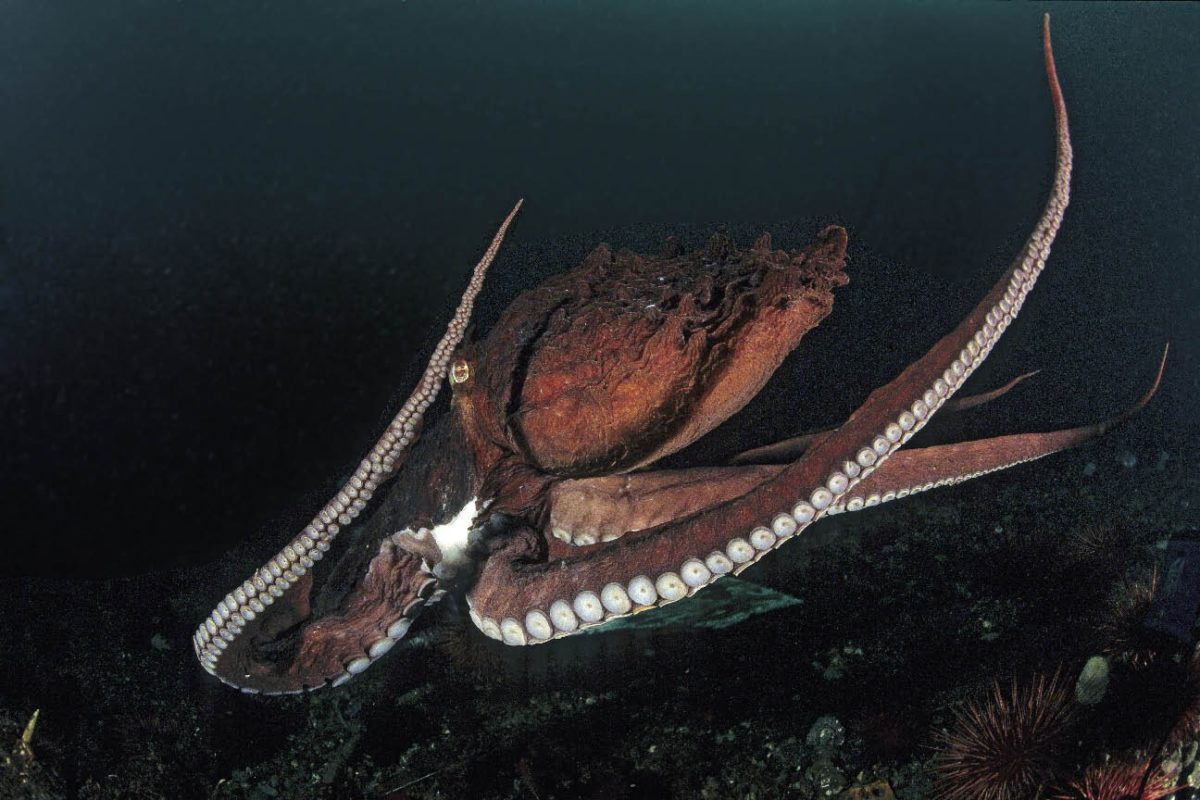

The octopus is an enigma to many, inspiring fear and wonder, but few people realise just how intelligent it is: it can learn simple mazes, can distinguish between shapes and patterns, uses landmark navigation while foraging, uses tools, shows playful behaviour and displays an individual personality. There are around 300 recognised octopus species, making up more than a third of the total number of known cephalopod species.

The giant Pacific octopus (Enteroctopus dofleini) is found in the Pacific Ocean – from California up to Alaska and over to Japan – and several subspecies are known. A mature giant octopus commonly weighs between 10kg and 15kg, although there have been (dubious) reports of specimens weighing as much as 272kg and measuring 9.6m from arm to arm. The one I photographed off Vancouver Island, British Columbia, was more than a metre in length.

Size is not always relative to menace, as proven by the greater blue-ringed octopus (Hapalochlaena lunulata), a creature the size of a golf ball but whose poison is powerful enough to kill humans – and there is no known antidote. This legendary creature produces a poison that contains tetrodotoxin, a neurotoxin also found in pufferfish and cone snails that causes motor paralysis and respiratory arrest, leading to cardiac arrest due to a lack of oxygen. I managed to find and photograph one in Papua New Guinea,

off the Walindi Plantation Resort.

SOFT INTELLIGENCE: WHERE TO FIND THEM

Atlantic bobtail squid Found from Iceland to northwest Africa, but easiest to find off southwest Ireland

Pfeffer’s flamboyant cuttlefish Has been found from Indonesia to Papua New Guinea and across northern Australia. Commonly found at Mabul Island in Malaysia and the Lembeh Strait off Sulawesi, Indonesia

Humboldt squid Eastern Pacific, from California to Tierra Del Fuego on the tip of southern Chile. A migratory species; night encounters possible over abyssal water off Mexico

Giant Pacific octopus Northern Pacific, from Japan to California. Encounters take place off Vancouver Island, Canada and in the murkier waters of Puget Sound, Seattle

Greater blue-ringed octopus Inhabits rubble coral in the tropical western Pacific; sightings in Papua New Guinea and Rajah Ampat, Indonesia

Chambered nautilus Found all over the tropical western Pacific; sometimes encountered at night or brought up in fish traps over deep water in Papua New Guinea

Pharaoh cuttlefish Distributed across the western Indian Ocean; has been observed off Thailand, the Maldives and in the Gulf of Oman